The top 10% own nearly 90% of the stocks.

That’s the bad news.

The good news is more people now own stocks in some capacity. That hasn’t always been the case.

The 1929 crash that kicked off the Great Depression was a massacre. The stock market fell more than 80%.

Plenty of people got wiped out but it wasn’t as widespread as you would think.

Just one and a half million people out of a population of 120 million had any exposure to the stock market heading into the Great Crash. A little more than 1% of the population owned stocks.

Although there were few households invested in the stock market at the time, a generation was scarred from witnessing such a dramatic crash.

Even with a post-war boom in the 1940s, a mega bull market in the 1950s, the birth of the star mutual fund manager in the 1960s and the nifty fifty of the 1970s, 50 years after the onset of the Great Depression, the number of people who owned stocks in the United States were in the minority.1

By the early 1980s, the share of households with a stake in the stock market was just 19 percent.

No one wanted anything to do with stocks, considering you could earn double-digit yields in bonds or money-market funds in the early 1980s.

The whole Death of Equities thing by the end of the 1970s didn’t help either.

The great bull market of the 1980s and 1990s changed all that.

In 1983, households with incomes of $250,000 or more owned 43% of all publicly traded stocks. By 1992, that share had dropped to 23%, while Americans with incomes of less than $75,000 saw their share jump from 24% in 1983 to 42% by 1992.

By the end of the dot-com bubble, retail investors were all in. Individual investors accounted for 30% of trading on the New York Stock Exchange, compared to just 15% in 1989.

The number of people who were invested in the stock market shot up to 60% by 2000.

By that point almost two-thirds of those who owned stocks had purchased their first share in one form or another after 1990. One-third of equity owners had made their first purchase after 1995.

The dot-com bubble wrecked a lot of portfolios but it did get people interested and invested in the stock market.

The stock market boom following the onset of the pandemic has had a similar, if more muted, impact on people’s interest in equities.

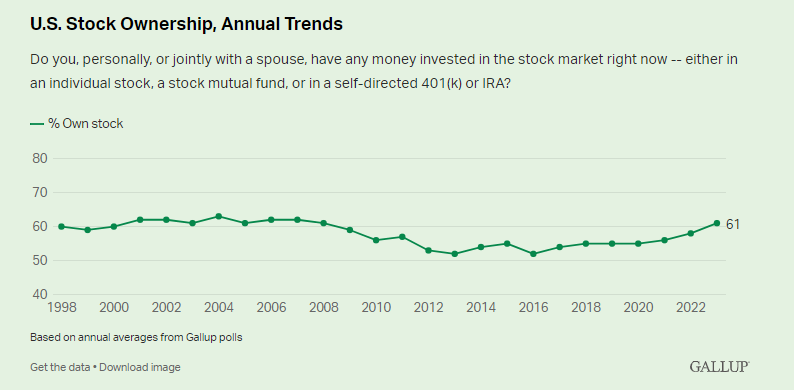

Here are the latest numbers from Gallup:

Sixty-one percent of U.S. adults say they have money invested in the stock market, the highest percentage Gallup has measured since 2008. Stock ownership fell during the Great Recession and stayed depressed for more than a decade, including lows of 52% in 2013 and 2016.

Most Gallup surveys prior to 2008 found 60% or more of U.S. adults owning stock.

Ownership in the stock market stagnated following the dot-com blow-up and headed in the wrong direction after the Great Financial Crisis.

Fewer people owned stocks in the mid-2010s than in the late-1990s.

Not a great trend.

But things have been slowly trending in the right direction since 2016 or so and have really moved higher since the 2020 mini-boom took hold.

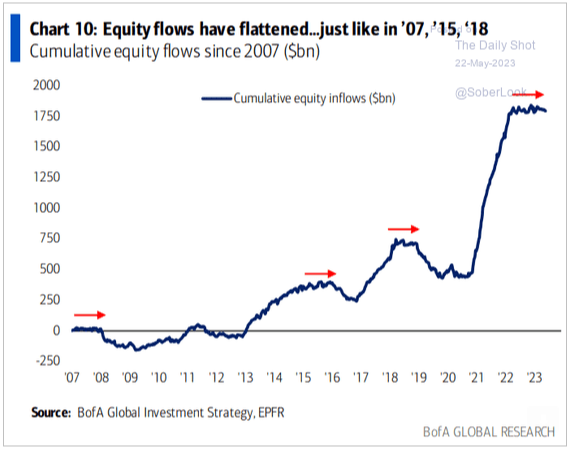

This trend becomes even more pronounced when you look at the flows into equities over time:

Investors were pulling money from stocks for a number of years following the 2008 crash, even after a new bull market was well underway.

But even with phenomenal returns throughout the 2010s it wasn’t until the pandemic boom times hit that flows into stocks took off like a rocket ship.

On the one hand, it’s a good thing more people are taking part in the revenues, profits and innovation that come from ownership in the stock market.

On the other hand, it’s too bad it took the bizarre pandemic stock market mania to get more people to buy stocks.

It’s a shame investors were net sellers of stocks and fewer people owned stocks both during and in the aftermath of the Great Financial Crisis.

It was a wonderful time to be a buyer of stocks. When prices are low that’s a good time to buy!

I understand why this happens. It’s human nature.

Some people simply cannot help themselves when it comes to buying after stocks go up and selling them after they go down.

Let’s just hope all of the people who came charging into the stock market these past few years stick around.

It would be a shame if a new group of investors entered because of a bull market and stopped investing because of a bear market.

The best time to buy stocks is during a bear market when prices are down.

Further Reading:

9 Underrated Investing Books