For almost 150 years, one of the most important variables in the economic cycle was war.

The cycle looked something like this:

- Governments would ramp up spending during wartime.

- This spending would increase wages and earnings, thus leading to prosperity.

- All that spending would eventually lead to an inflationary spike.

- Prosperity would inevitably be followed by a hangover once that spending dried up when the wars were over.

- A deflationary depression would follow and then the cycle would start all over again with the onset of the next war.

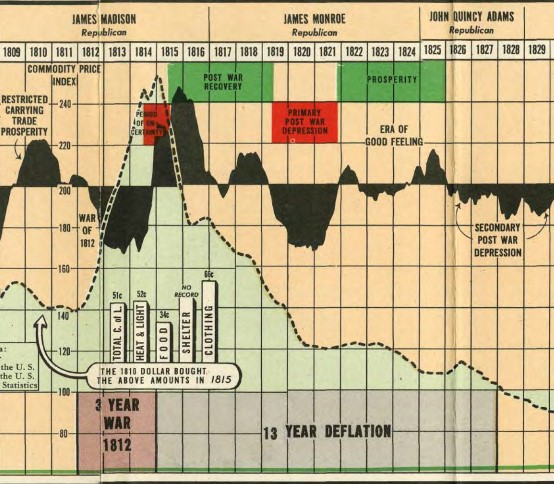

This occurred during the War of 1812:

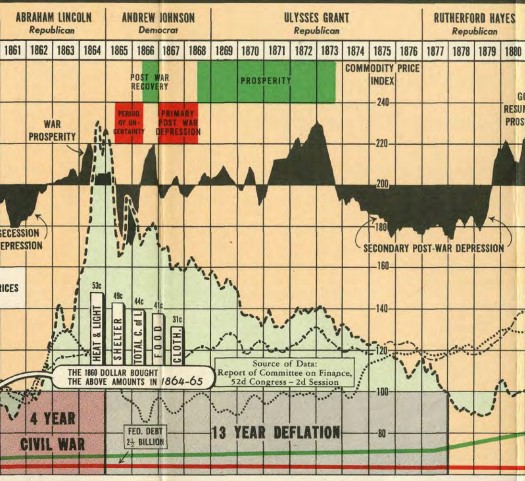

The Civil War:

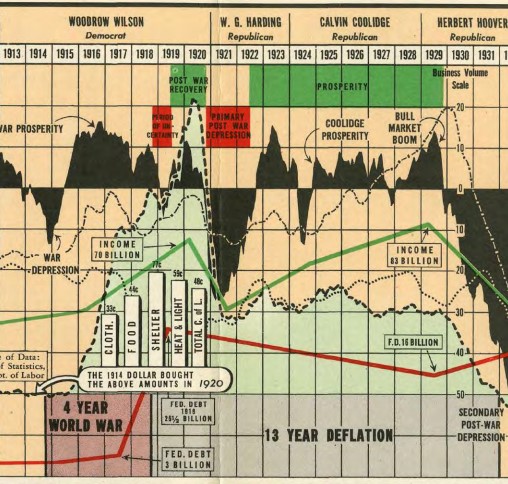

And World War I:

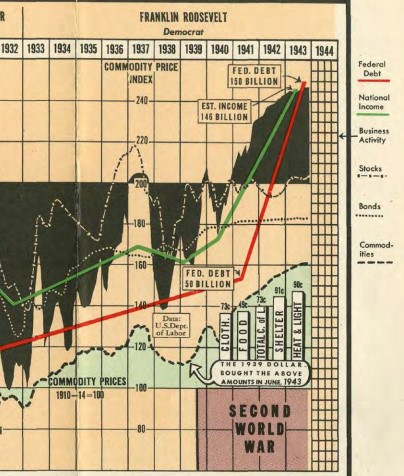

You could basically set your clock to it. The World War II economic playbook started out the same way:

But the cycle changed in the aftermath of WWII.

We got the war-time prosperity and inflation but never the deflationary depression on the other side. There was a minor recession in 1945 but never a crash that sent the system reeling. WWII is an economic anomaly that changed the trajectory of the United States for years to come in terms of growth, jobs, income, demographics and wealth inequality.

This is the story of why that time was different and how World War II radically altered the economic landscape for years to come.

*******

Many of the wealthiest business magnates in history were born in the same decade, proving timing can be everything when it comes to building empires.

Andrew Carnegie (born in 1835), Jay Gould (1836), J. Pierpont Morgan (1837) and John Rockefeller (1839) all built their empires following the post-Civil War industrial economic boom. These titans of industry would usher in the Gilded Age, a period of rapid economic growth, technological innovation, and industrialization.

This period also ushed in a huge influx of the working class, but it was mainly a small handful of the upper class that built vast fortunes on the backs of the working class.

The average annual wage of all American workers in the year 1900 was in the range of $400-$500. Andrew Carnegie made 20,000 times that much the very same year.

Following the Panic of 1907 and depression of 1921, the U.S. economy would go on a tear unlike it had ever seen in the roaring 1920s. It was another period of massive technological innovation with the addition of cars, telephones, movies, radios, and appliances to the consumer landscape.

Unfortunately, by the end of the decade, most of the gains had once again gone mainly to the wealthy class. As the country was just about to head into the Great Depression in 1929, Brookings Institution found that just 2.3% of American families had incomes of more than $10,000 a year. Only 8% made more than $5,000 annually. And more than 70% of families lived on less than $1,000 a year. They further estimated that nearly 60% of American families had incomes that placed them below the poverty line.

If the Gilded Age set off a new era of wealth inequality, the roaring 20s kicked it into overdrive.

When the Great Depression hit, the stock market crash decimated investors, with stocks falling upwards of 85% in less than 3 years. When stocks and valuations rise as fast as they did in a period such as the late-1920s1 the initial reaction from most people who follow the markets would be that “everyone” must have been invested at the time. So when the crash hit, all those noobwhales who jumped in when things were good surely rushed to the exits when things got bad.

But that’s just not the case.

There were only 1.5 million or so people invested in stocks in 1929 or a little more than 1% of the US population.2 It was mostly the wealthy class who were invested in the stock market at the time but even with the market crash, the Great Depression had a far greater impact on the lower-income class.

Here’s how Frederick Lewis Allen described this in his book about the aftermath of the 1920s:

Among the comparatively well-to-do people of the country (those, let us say, whose pre-Depression incomes had been over $5,000 a year) the great majority were living on a reduced scale, for salary cuts had been extensive, especially since 1931, and dividends were dwindling. These people were discharging servants, or cutting servants’ wages to a minimum, or in some cases “letting” a servant stay on without other compensation than board and lodging. In many pretty houses, wives who had never before—in the revealing current phrase—“done their own work” were cooking and scrubbing. Husbands were wearing the old suit longer, resigning from the golf club, deciding, perhaps, that this year the family couldn’t afford to go to the beach for the summer, paying seventy-five cents for lunch instead of a dollar at the restaurant or thirty-five instead of fifty at the lunch counter. When those who had flown high with the stock market in 1929 looked at the stock-market page of the newspapers nowadays their only consoling thought (if they still had any stock left) was that a judicious sale or two would result in such a capital loss that they need pay no income tax at all this year.

The wealthy class was forced to cut back but most were still relatively wealthy. It was those who lived below the poverty line that had trouble finding work, food, and even shelter.

The New Deal created a series of financial programs, reforms, regulations, and relief that stopped the bleeding from the Great Depression but prosperity didn’t return until the massive borrowing and defense spending that went into play for WWII.

Because of the technological innovations that were sweeping the country in the early 20th century, the productivity of American business was already taking off in the lead up to the war, even during the dreadful 1930s. Output per hour of work increased by 12% from 1900-1910, 7.5% during the 1910s, 21% during the 1920s and an amazing 41% during the 1930s.

Even with this productivity boom, confidence was still low for most business leaders as the scars from the Great Depression ran deep so most companies still pumped the brakes in terms of operating at or near full capacity. That all changed once the war started.

New plants sprang up on the double to produce tanks, trucks, weapons, and anything else the U.S. government needed for the war. Allen explains how this set off an unprecedented spending spree:

Now, with the coming of the war emergency, the brakes were removed. For the military planners at Washington had conceived their plans on a truly majestic scale. By the end of the war the United States had a total of over twelve million men in service, as against less than five million in World War I. The devisers of the effort had resolved that these forces of ours would be the best armed, best equipped, best supplied, and most comfortably circumstanced in history—which they were. And we had to supply not only our own forces, but others too. The result, in terms of output and of cost, was astronomical. By the end of 1943 we were spending money at five times the peak rate of World War I. During the nineteen-thirties, critics of the New Deal had become apoplectic over annual federal budgets of seven or eight or nine billions, which they felt were carrying the United States toward bankruptcy; during the fiscal year 1942 we spent, by contrast, over 34 billions; during 1943, 79 billions; during 1944, 95 billions; during 1945, 98 billions; during 1946, 60 billions. For the last four of these years, in fact, our annual expenditures were greater than the total national debt which had been a matter of such grave concern during the Depression. That national debt had risen from 19 billions in Hoover’s last year in office to 40 billions in 1939—and here was the government, only a few years later, spending up to 98 billions per year, and thus piling the national debt up to 269 billions by 1946! These colossal sums made anything in the previous history of the United States look like small change.

By 1945, GDP was 2.4 times the size of the economy in 1939. Allen called it, “the most extraordinary increase in production that had ever been accomplished in five years in all economic history.”

Everyone who wanted a job could find work. Consumers spent money like crazy, finally letting go of the frugal spending habits that had been ingrained in them since the Great Depression. Following one of the worst economic decades in history along with two world wars, it must have been a relief for people to spend some money on themselves for a change.

Surprisingly, this economic boom didn’t benefit the wealthy class as much as it had in the past. It was the working class who experienced the majority of the gains during the war. The average pay for manufacturing workers was up almost 90% between 1939 and 1945, far outpacing the 29% inflation during that time. And it was people with the lowest incomes who experienced the biggest bang for their buck.

Here’s Allen again:

Who was getting the money? Generally speaking, the stockholders of the biggest corporations were not getting very much of it. These corporations were in many cases getting huge war orders, and thus consolidating their important positions in the national economy; but excess-profits taxes, along with managerial caution over the uncertainties of the future, and with the recollection of the embarrassing scandals of 1918 war profits, combined to keep their dividend payments at modest rates. The stock market languished. Big capital, as such, was having no heyday.

The principal beneficiaries, generally speaking, were farmers; engineers, technicians, and specialists of various sorts whose knowledge and ability were especially valuable to the war effort in one way or another; and skilled workers in war industries—or unskilled workers capable of learning a skilled trade and stepping into the skilled group.

What do these figures mean in human terms? That millions of families in our industrial cities and towns, and on the farms, have been lifted from poverty or near-poverty to a status where they can enjoy what has been traditionally considered a middle-class way of life: decent clothes for all, an opportunity to buy a better automobile, install an electric refrigerator, provide the housewife with a decently attractive kitchen, go to the dentist, pay insurance premiums, and so on indefinitely.

Not only did the war lift a large swath of the population into the middle class, but it also narrowed the gap between the top and the bottom in terms of wealth inequality. Between the start of World War I and the end of World War II, the difference in the share of national income between the top 5% of earners and the bottom 95% narrowed from 30% to 19.5%. The share of the top 1% fell from 13% to 7%. And the disposable income for all Americans rose nearly 75% between 1929 and 1950.

Housing got crushed during the Great Depression and again the war was the spark to turn things around. Housing starts fell from one million a year to fewer than 100,000 by the time the damage was done. When people returned from the war looking to settle down, housing had a lot of catching up to do.

A federal housing bill, a baby boom, and the huge number of soldiers coming home looking to settle down helped the number of new single-family homes being built grow from 114,000 in 1944 to 937,000 by 1946 and a massive 1.7 million by 1950. Owning a home became the new American dream and basically anyone with a decent job could afford a home by the 1950s.

World War II more or less created the middle class.

And the baby boom that followed, aided by the GI bill which allowed soldiers to buy their first home and get a college education, ensured the middle-class way of life had a strong foundation. The economy went from a focus on military spending to a focus on consumer spending.

Prices and inflation leveled out and there was a two-decade or so period where things were just about perfect for the stock market and the economy.

After this goldilocks period of relative economic calm, we’ve witnessed many of these trends reverse.

Wage growth has slowed for the middle class considerably. Inequality in America grows by the year as the gap between the haves and the have nots continues to widen. Inflation in the things we want (tech) remains subdued but inflation in the things we need (healthcare, education, housing prices) has made it difficult for many families to get ahead financially.

A number of questions come to mind when thinking through the economic impact of WWII:

- Did WWII interrupt a number of established trends that were already in place?

- Was the growth of the middle class following the war an anomaly?

- Is wealth inequality a feature, not a bug, of our capitalist system?

- Do we need some sort of abnormal shock to the system to narrow the gap between the top and bottom when it comes to wealth inequality?

- Is it possible inflation is mostly a thing of the past if we don’t have any more massive wartime spending booms?

I don’t know the answers to these questions because these topics are extremely complex. But it’s worth considering the possibility that WWII changed the economic trajectory of the country.

It’s also worth considering how many of those changes have now been wrung out of the system.

Sources:

The Big Change: America Transforms Itself 1900-1950

Since Yesterday: The 1930s in America

The Fifties

Further Reading:

Business Booms & Depressions: 1775-1943

1In a three-and-a-half-year period from the 2nd quarter of 1926 through the 3rd quarter of 1929, the S&P 500 was up more than 200%. That’s an annualized return of almost 40% per year.

2One of the biggest reasons that crash was so spectacular is because so many investors who were in the market took on far too much borrowed money to buy shares. So it didn’t take much to wipe them out, causing a cascading of selling.