Robert Shiller has a free online database of historical stock market data I’ve been using for years.

Going back to 1871, Shiller has data on historical interest rates, dividends, earnings, inflation and valuations.

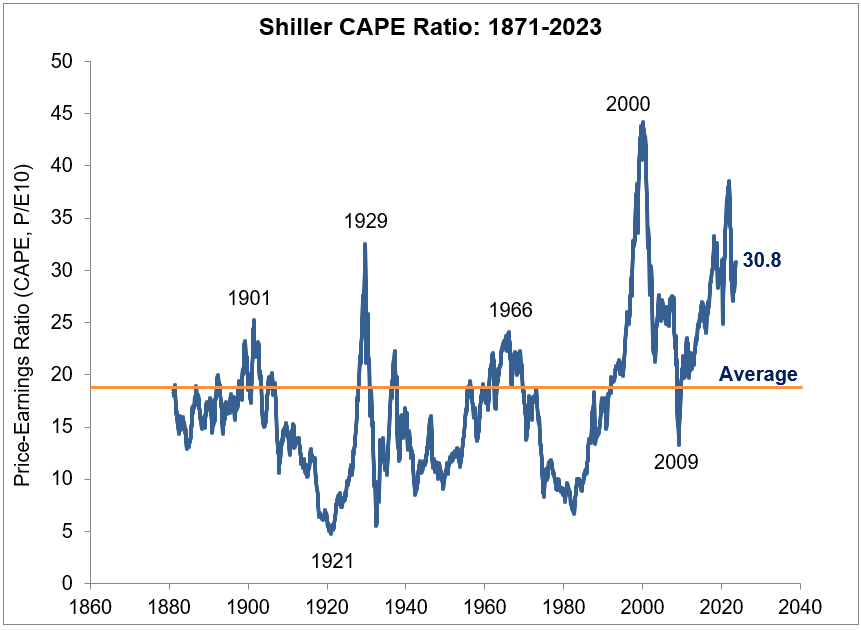

His preferred valuation measure is the cyclically-adjusted price to earnings (CAPE) ratio

The average CAPE ratio going back to 1871 is 17.4x the previous 10 years of inflation-adjusted earnings for the U.S. stock market:

We’re talking over 150 years of data here so this is the very long-term when it comes to averages.

If we look at valuations going back to 1990, out of slightly more than 400 monthly observations, the CAPE ratio has been below the long-term average for just 22 months. That’s around 5% of the time.

Mind you, this is not valuations at screaming buy levels, just below average.

There was a 12-month period of below-average multiples in 1990-91. Valuations didn’t go below the long-term average again until a 10-month period in 2008-09.

So if you waited to buy stocks until valuations were reasonable you had exactly two chances in the past three-plus decades.

And since 2010, there hasn’t been a single monthly reading that’s below average. In fact, there hasn’t been a single monthly reading below 19.6x since the end of 2009.

After 2009 you didn’t once get a chance to buy when valuations were below average.

As early as 2010, people were already sounding the alarm bells about valuations being too high:

Here’s Henry Blodget at the time:

As the latest update of Professor Robert Shiller’s cyclically adjusted PE ratio shows, US stocks are now more than 30% overvalued, at 21x earnings. That’s more reasonable than the 100%+ overvaluation in 2000, but it’s closing in on the level of the three other bubble peaks of the 20th Century: 1901, 1929, and 1966.

He wasn’t alone.

It’s funny looking back on the low interest rate period of the 2010s because it seems like such a lay-up that stocks would take off in such a scenario. But at the time people were saying those low rates were going to be the cause of low returns (because everything was priced to the 10 year).

And the Fed was going to cause hyperinflation, not a bull market in stocks.

Remember PIMCO’s new normal of low rates, low growth and low financial market returns?

Well they got two out of the three right.

I sat through countless presentations in the early part of the last decade from professional investors telling me valuations for U.S. stocks were in the 97th percentile or something of historical norms and that we should expect much lower returns going forward.1

Heck, I wrote about the psychology of lower returns all the way back in 2014.2

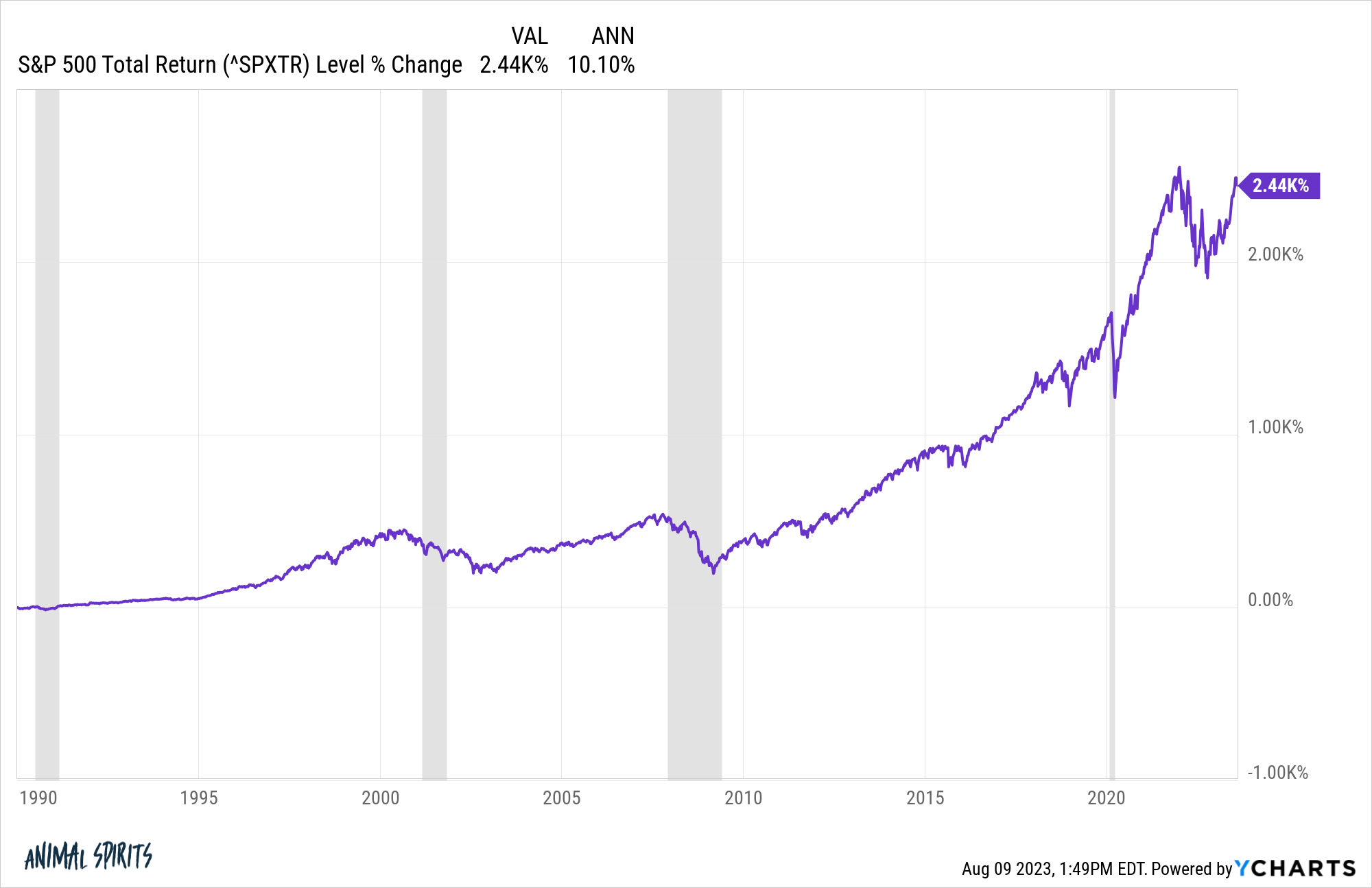

The U.S. stock market has been overvalued 95% of the time since 1990 yet it’s up more than 10% a year in that time:

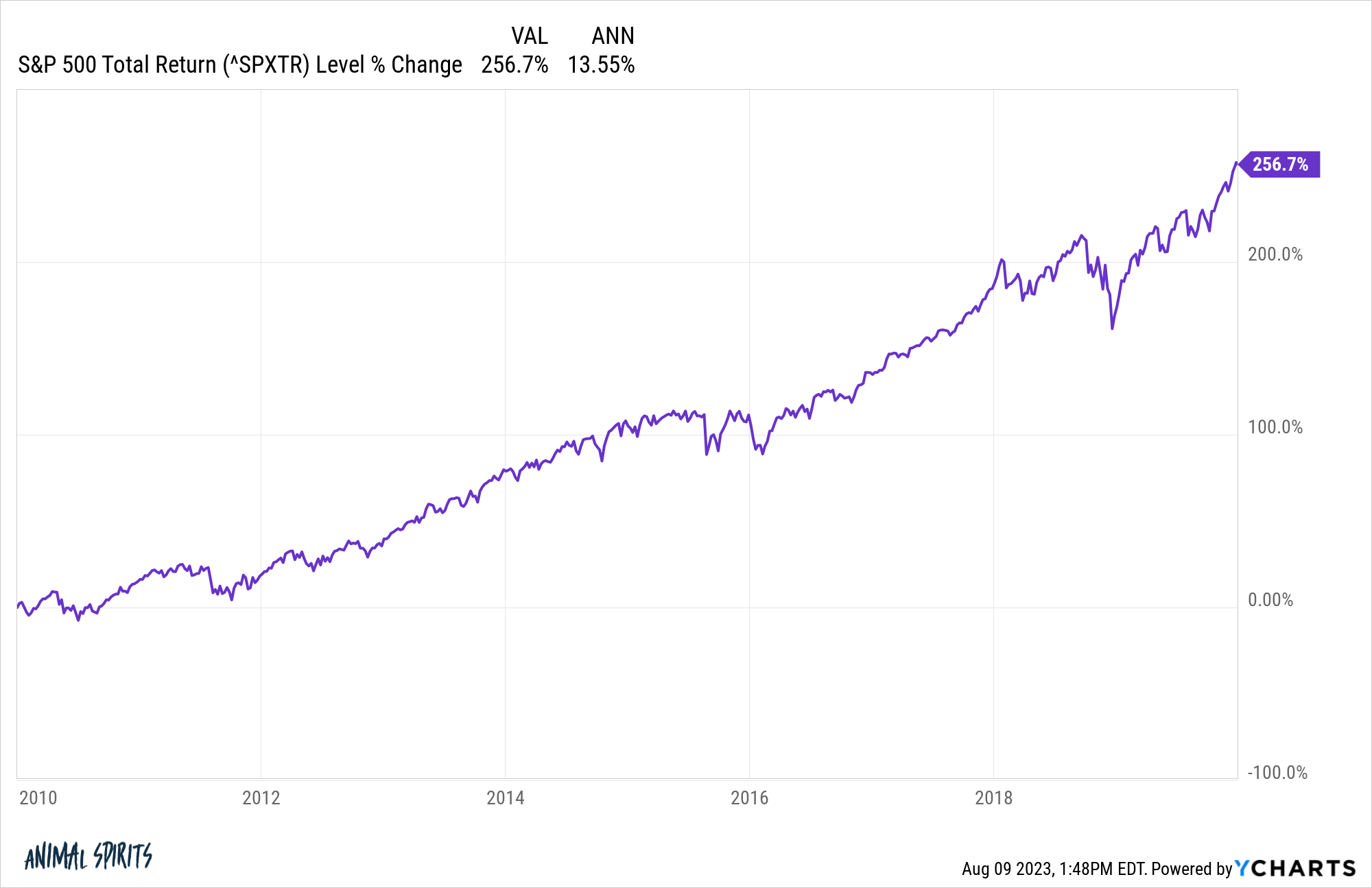

In the 2010s the S&P 500 did nearly 14% per year in returns, despite people shouting about how overvalued it was the entire ride up:

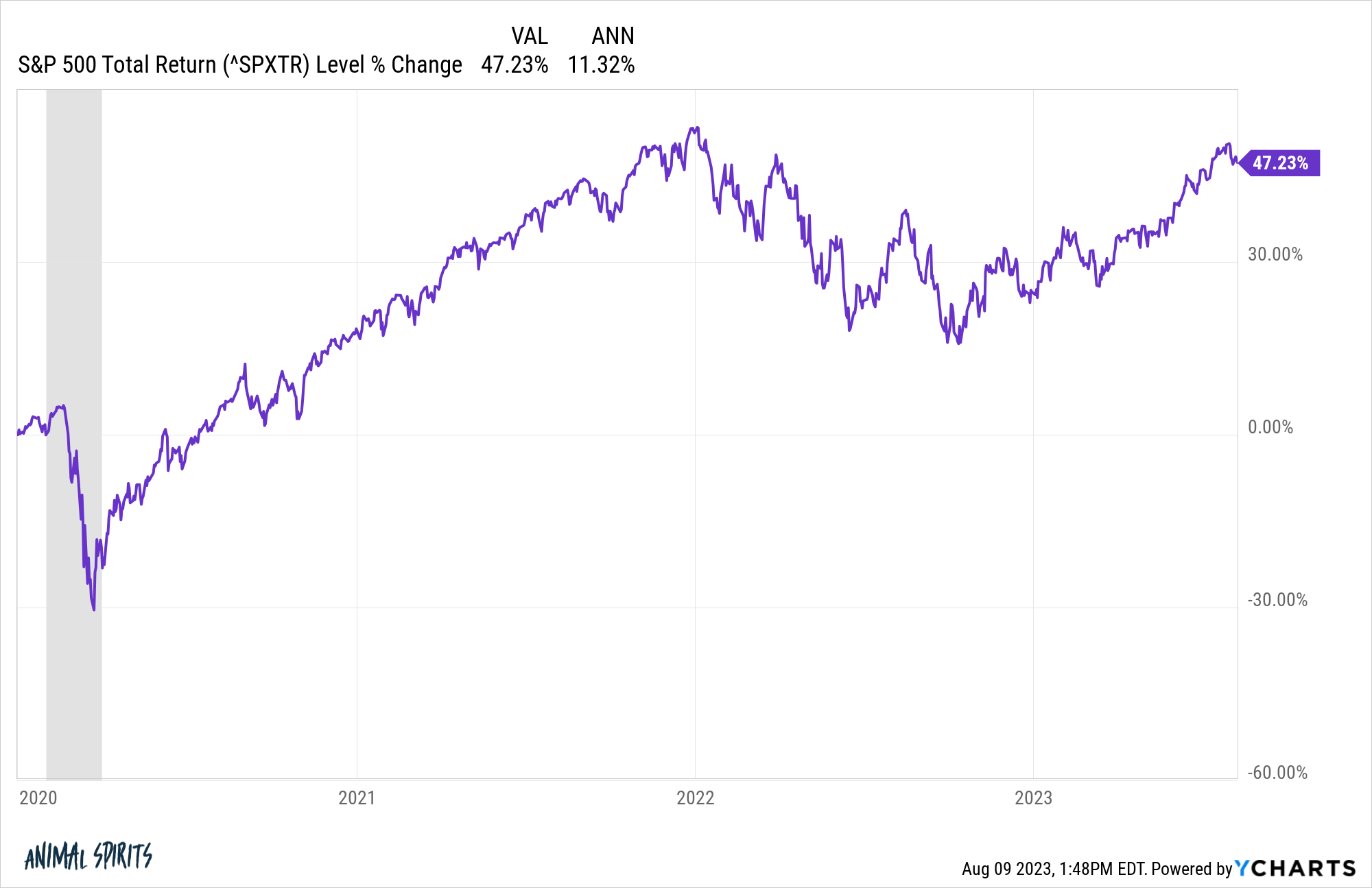

And in the 2020s, a decade in which we’ve experienced a pandemic, 40-year high in inflation, two bear markets and one of the most aggressive Fed hiking cycles in history, the S&P 500 is up more than 11% per year:

I know what you’re thinking — Ben, you’re crazy! Haven’t you read this 40 page research report from the Financial Analysts Journal that shows how important valuations are?!

Yes, I’ve probably read it. I know the data. I’ve written about it many times before (here, here and here).

I’m not saying this will continue. I’m not naive.

At some point higher than average returns will lead to lower than average returns. That’s how long-term averages work in the stock market.

My point here is we in the investment community, myself included, probably pay way too much attention to valuations.

Understanding financial market history is absolutely a prerequisite when it comes to investment success.

But becoming a slave to the data can become a liability if you don’t put it into context.

The funny thing is those historical averages we now use for comparison purposes were completely unknown to 99% of investors who came before us in the stock market.

They either didn’t have the data or the knowledge or care to understand such fundamentals. Knowing about valuations has probably lost more people money over the years than it’s made them.

I’m not saying valuations don’t matter at all. They probably matter for individual stocks more than the overall market but valuations do matter at the extremes (like 1999 for instance).

It’s just that markets rarely get to the extremes. Most of the time we’re somewhere in the middle of insanely cheap and insanely expensive.

People pay way too much attention to valuations at the stock market level.

There are plenty of other factors that matter more than valuations. Things like demographics, money allocation decisions, investor risk appetite, the prevalence of tax-deferred retirement vehicles, the trillions of dollars controlled by financial advisors, how institutions are positioned and more.

The past 15 years of U.S. stock market returns are a wonderful example of how hard it is to predict what’s going to happen next.

Sure, no one could have known the Fed would keep rates at 0% for so long. No one expected tech stocks would grow to gargantuan levels. And no one had any idea a pandemic would cause governments around the globe to spend trillions of dollars.

But maybe that’s the point.

Predicting the future is hard, especially when it comes to the markets.

The stock market doesn’t care all that much about historical averages most of the time.

Do valuations matter?

The majority of investors would probably be better off if they ignored them most of the time.

Michael and I talked stock market valuations and much more on this week’s Animal Spirits video:

Subscribe to The Compound so you never miss an episode.

Further Reading:

Is this the Top?

Now here’s what I’ve been reading lately:

- Paychecks matter more than portfolios when building wealth (Dollars & Data)

- 50 charts that matter right now (Yahoo Finance)

- 5 lessons popular personal finance gets wrong (Gen Y Planning)

- Wealth vs. income (The Rational Walk)

- Why do people think the economy is bad? (Kyla Scanlon)

- Mortgage rate envy (NY Times)

Books:

- A Piece of the Action: How the Middle Class Joined the Money Class Joe Nocera

- The Affluent Society by John Kenneth Galbraith

1To be fair most of these people were trying to sell some hedge fund or alpha-like strategy that didn’t rely on the stock market going up.

2The S&P 500 is up 11.9% annually since I wrote that piece.