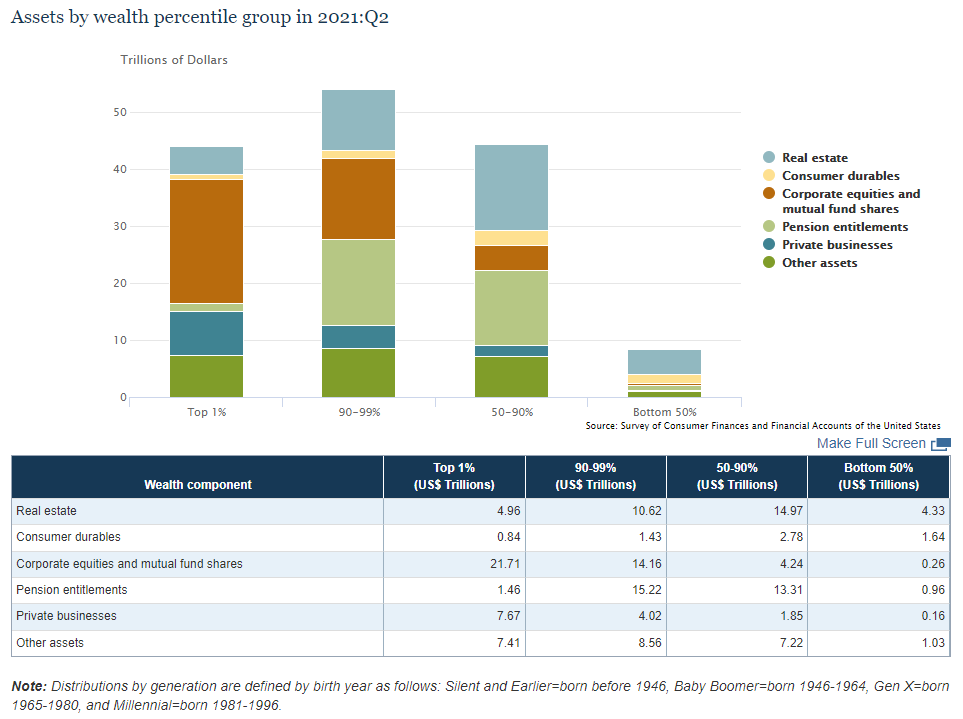

The Federal Reserve has a quarterly report that breaks out the assets held by wealth percentile of U.S. households:

This data is kind of depressing.

The top 10% owns 45% of the housing market while the bottom 90% owns 55% of real estate in this country.

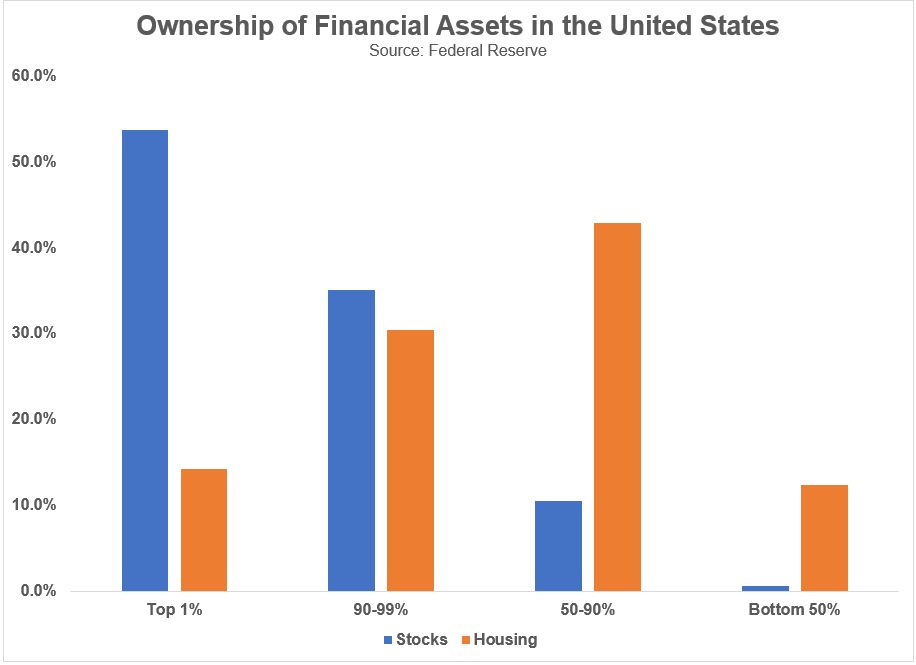

And if you think this seems out of whack just wait until you see the ownership numbers for financial assets.

The top 1% now owns nearly $22 trillion in stocks and funds which represents almost 54% of the total ownership. The top 10% owns 89% of the stocks in this country, meaning the bottom 90% owns just 11% of the stocks.

This is overkill but here are these numbers in chart form to illustrate how imbalanced things are:

This is a problem.

I suppose the good news about a scalding hot housing market is the rest of the population who don’t own as many stocks aren’t being completely left behind. But we can’t bank on the housing market putting up such huge returns year in and year out.

The current housing market is an outlier.

It’s possible the stock market will have lower returns from current levels going forward but the fact that equity ownership is tied up in the hands of so few means the wealth inequality gap will continue to widen.

Although the top 10% own the bulk of the stock market, it’s estimated around 50% of the country has some ownership in the stock market.

This number is far too low for my liking but it’s much higher than we’ve seen historically.

No one can agree with 100% certainty what caused the Great Depression of 1929-1932. Some people think an overheating economy caused the stock market to crash 85%. Other people think the stock market crash brought down the economy.

Based on the ownership structure at the time, it’s hard to argue the stock market was the main catalyst.

Surprisingly few Americans were even invested in the stock market in the 1920s. In The Great Crash 1929, John Kenneth Galbraith estimates just 1% or so of the population even held shares in the stock market at the time of the great crash:

The member firms of twenty-nine exchanges in that year reported themselves as having accounts with a total of 1,548,707 customers. (Of these, 1,371,920 were customers of member firms of the New York Stock Exchange.) Thus only one and a half million people, out of a population of approximately 120 million and of between 29 and 30 million families, had an active association of any sort with the stock market.

And that crash didn’t exactly engender a sense of faith in the stock market for those who witnessed it. An entire generation of people wanted nothing to do with the stock market following the Great Depression.

Even with the huge bull market of the 1950s, only 4-5% of the country owned shares either directly in a corporation or indirectly in a mutual fund by the middle of that decade.

The 1960s brought a boom in growth stocks and mutual funds while the 1970s saw commissions fall off a cliff, the onset of index funds and the 401(k) defined contribution retirement system.

Still, by the early 1980s the percentage of Americans who owned stocks was still just 20% or so. It wasn’t until the bull market of the 1980s and 1990s that interest in the stock market took off for real.

Maggie Mahar explains:

The share of households with a stake in the market grew from just 19 percent in 1983 to over 49 percent in 1999. And those lucky enough to have the price of admission watched their wealth soar. By ’98, the 25 to 30 percent of American families with household incomes north of $75,000 found that since ’89, their net worth had increased by some 20 percent. The wealthiest 5 percent watched their retirement funds grow by a dazzling 176 percent.

Just like today, the rich only got richer, but the fact that stock ownership went from 19% in 1983 to 49% in 1999 was a giant leap forward. The bull market brought in tons of new investors:

In 2002, fully 56 percent of those who owned stocks or stock funds had purchased their first shares sometime after 1990, while 30 percent of all equity investors had gotten their feet wet only after 1995.

I don’t know how much longer the current bull market will last. But we’re already beginning to see signs of a similar leap forward when it comes to young people getting involved in the markets.

Robinhood announced in their S1 more than half of the 18 million accounts on their platform were the first-ever brokerage accounts opened by their clients. The problem is the average account size on Robinhood is just $4,500.

So even millions of new investors won’t make much of a dent in the overall wealth pie relative to the top 10% who owns most of the stocks.

If we’re looking for a silver lining here, it’s that there has never been a better time to be a new investor. Fees are lower than ever. Access to investing platforms now sits in the palm of your hand. The barriers to entry are lower than they’ve ever been when it comes to getting more people involved in the markets.

Unfortunately, the final frontier is access to capital.

Rich people simply have more money so they save and invest more. And higher equity ownership by the wealthiest households means they will only continue to get richer.

I wish I had a good solution for this but I don’t see this dynamic changing anytime soon.

The best we can do now is get more people invested in the stock market so they can take part in the long-term upward trajectory of innovation and profits.

Further Reading:

9 Underrated Investment Books