“Culture is one of the two or three most complicated words in the English language.” – Raymond Williams

In 2005, a man was sitting on a bus in Nigeria minding his own business when all of the sudden he let out an ear-piercing scream.

Wasiu Karimu began shouting that his genitalia had magically disappeared into his own body.

He immediately grabbed the woman seated next to him and demanded that she restore his stolen manhood at once.

Karimu continued shouting at the woman as they got off the bus which caused a commotion. The police eventually brought them down to the station to settle their dispute.

When asked to prove his claim of penis theft, the man told the police commissioner his organ had gradually returned to its rightful place.

This may sound like a case of a mentally unstable person making an outlandish claim. But thousands of people in places like Nigeria, Singapore and parts of China have experienced the phenomenon known in medical literature as koro or magical penis theft.

It’s a situation where people, mostly men, have the feeling their genitals are being sucked into their bodies. When doctors examine these patients, the men often look down and claim it had magically reappeared.

Magic penis theft is what is referred to as a culture-bound syndrome which are diseases that are more prevalent in certain societies or cultures.

Frank Bure traveled to Nigeria, China and other places around the globe to better understand this phenomenon for his book The Geography of Madness: Penis Thieves, Voodoo Disease and the Search for Meaning of the World’s Strangest Syndromes.

Bure goes into great detail about how the power of story-telling and fear can be used to create not only belief but feelings of physical trauma.

One documented outbreak of koro occurred in Singapore during the 1960s where nearly 500 men in one region experienced this sensation. Every single patient who was interviewed by doctors claimed to have heard stories about magical penis theft before they experienced it.

Bure explains how these cultural syndromes can take hold:

The idea of a bioloop is the most elegant solution: the notion that there is a kind of circle of causation, that mental and physical states are connected so that each alters the other to some degree. A biolooping effect doesn’t imply that one is real and one is not. It doesn’t imply that biology doesn’t matter or that drugs don’t work. It doesn’t mean that thoughts are magical or that we can believe anything we want and then produce it. It doesn’t even imply that any of these things are easily divided into different categories. Rather, they are all part of the same tangled organism. Cultural syndromes—and all syndromes—are a result of these loops. Each of us exists in a swirl of belief and expectancy and biology. Each of us is a very strange loop.

For instance, after the fall of the Berlin wall and Germany was reunified, they conducted a national health survey. There was a stark difference between the rates of lower back pain between East and West Germany. West Germans experienced nearly 20% more lower back pain than East Germans.

The reasoning for lower back pain is notoriously difficult to ascertain, so the researchers continued tracking these numbers. A decade later, that disparity was gone, and the rates within the two sides began to move in unison.

Panic attacks occur in more than 11% of Americans but less than 3% of Germans. Social anxiety disorder averages nearly 5% of the population in the United States but just 0.2% in China.

Bure explains, “All of these conditions appear to be not just biological, but biocultural, which is to say, they are shaped by both biology and culture. This is not the same as saying they aren’t real. It’s saying that, while there is biology at work, there are other links in the chain.”

I believe culture-bound syndrome exists in the markets as well.

One of the simplest explanations offered for the continued strength of the U.S. stock market in recent years is generationally low interest rates. If there are no safe yield alternatives, investors are forced to go out further on the risk curve.

And this makes sense in theory until you realize the fact that rates are even lower in places like Europe and Japan yet they haven’t seen the same level of euphoria in their markets.

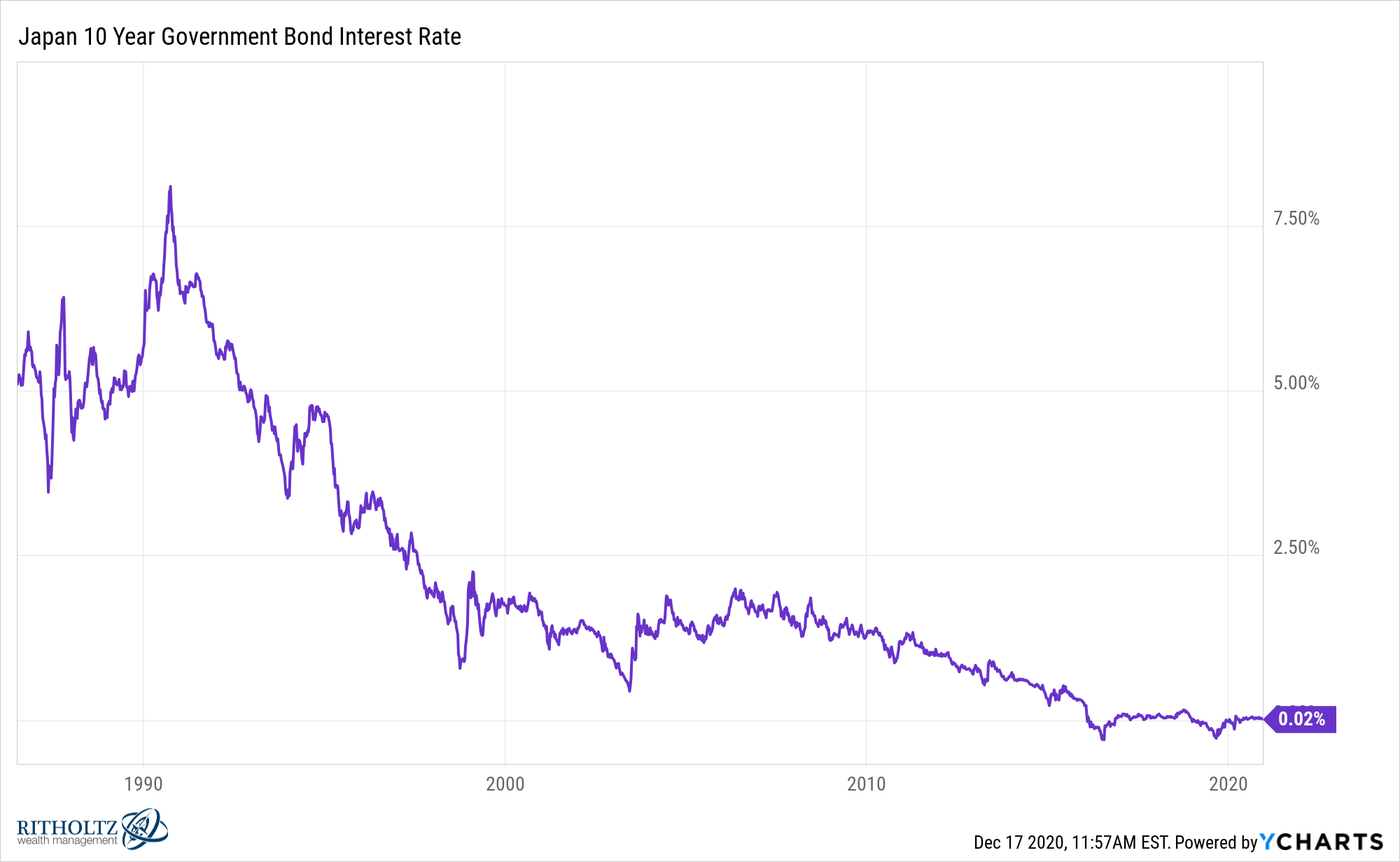

Yields for 10 year government bonds in Japan have been under 3% since 1996 and less than 1% since 2010:

Yet there hasn’t been a whiff of speculation in Japanese markets in that time.

In keeping with the penis theft analogy, interest rates are the physical state investors have had to deal with yet the mental state hasn’t come into play to create the bioloop.

It could be the people of Japan are still gunshy from creating perhaps the biggest asset bubble in history back in the 1980s.

But there is also a cultural difference between Americans and the Japanese from a risk-taking perspective.

The New York Times recently highlighted a business in Japan that is more than 1,000 years old. Japan is also home to more than 33,000 businesses that are at least 100 years old (over 40% of the world’s total). More than 3,100 have been in business for at least 200 years and 140 for more than 500 years.

This is an amazing feat and one which will likely never take place with American businesses. We simply don’t have the patience. We’re a country of risk-takers, entrepreneurs, shareholders and gamblers.

It’s in our nature.

We cannot help ourselves which is both a blessing and a curse. It’s one of the reasons the U.S. stock market has dominated the last century but also the reason we can’t help but create spectacular booms and busts on a regular basis.

That’s why we have bounced around from the dot-com bubble at the end of the 1990s to the housing bubble of the mid-2000s to whatever this current speculative Robinhood/SPAC/tech/IPO boom is.

This is one of my all-time favorite Onion1 headlines:

It’s funny because it’s true.

We don’t need low interest rates to see a boom in risk appetite. Interest rates were nearly 10% when stocks shot up 40%+ in 1987 before the biggest one-day crash in history. Rates were in the 5-6% range for much of the dot-com bubble.

Low interest rates in and of themselves don’t cause massive speculation in the markets.

But if you combine low interest rates with a culture that is obsessed with risk-taking and gambling, that could become a powerful speculative elixir.

Further Reading:

Trying Not to Get Lost in Translation

1For those who are aware of the Onion, they are a satirical publication but their headlines are often right on the money.