I came across a bunch of charts in the past few weeks about Europe’s economic and market struggles.

Let’s take a look.

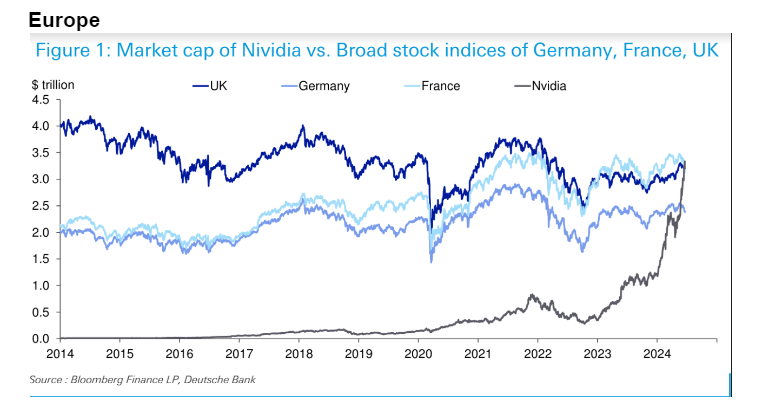

These charts that show how the biggest companies in the U.S. stock market are as big or bigger than some of the biggest economic powers in Europe always get me:

The UK has something like 1,900 stocks on the London exchange. The main exchanges in France and Germany have roughly 800 and 500 stocks, respectively. Nvidia has fewer than 30,000 employees.

I’m not sure there is anything actionable about charts like this, but it makes you think.

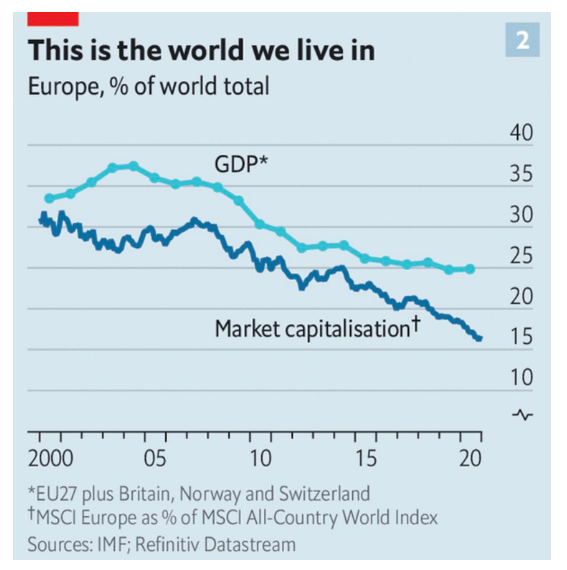

The Economist has a chart that shows the slide in both GDP and stock market capitalization in Europe this century:

Europe makes up 25% of world GDP but just a little more than 15% of global stock market capitalization. America has roughly the same weight in GDP at 25% but makes up more than 60% of the world market cap.

The United States (China too) is dominating Europe on the private market side of the ledger too:

Things were fairly even in the early-2010s. Not anymore.

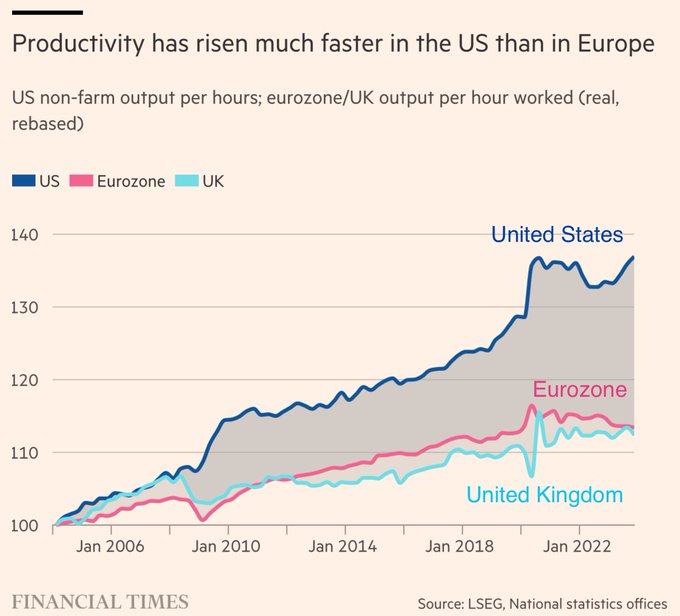

The Financial Times has a chart that shows the divergence in productivity since just before the Great Financial Crisis:

It’s like someone flipped a switch after the 2008 crash when U.S. workers and companies became more efficient than the Eurozone.

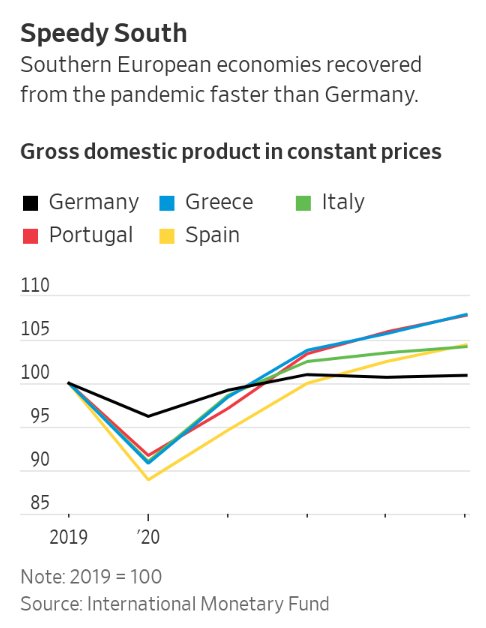

The Wall Street Journal had a story this week that makes it sound like free-spending American tourists are the Eurozone’s only economic driver:

They show that tourist countries have experienced higher growth since the pandemic:

This is probably a bit of a stretch, but you can’t deny that the Eurozone has fallen behind this century when it comes to economic and financial market growth.

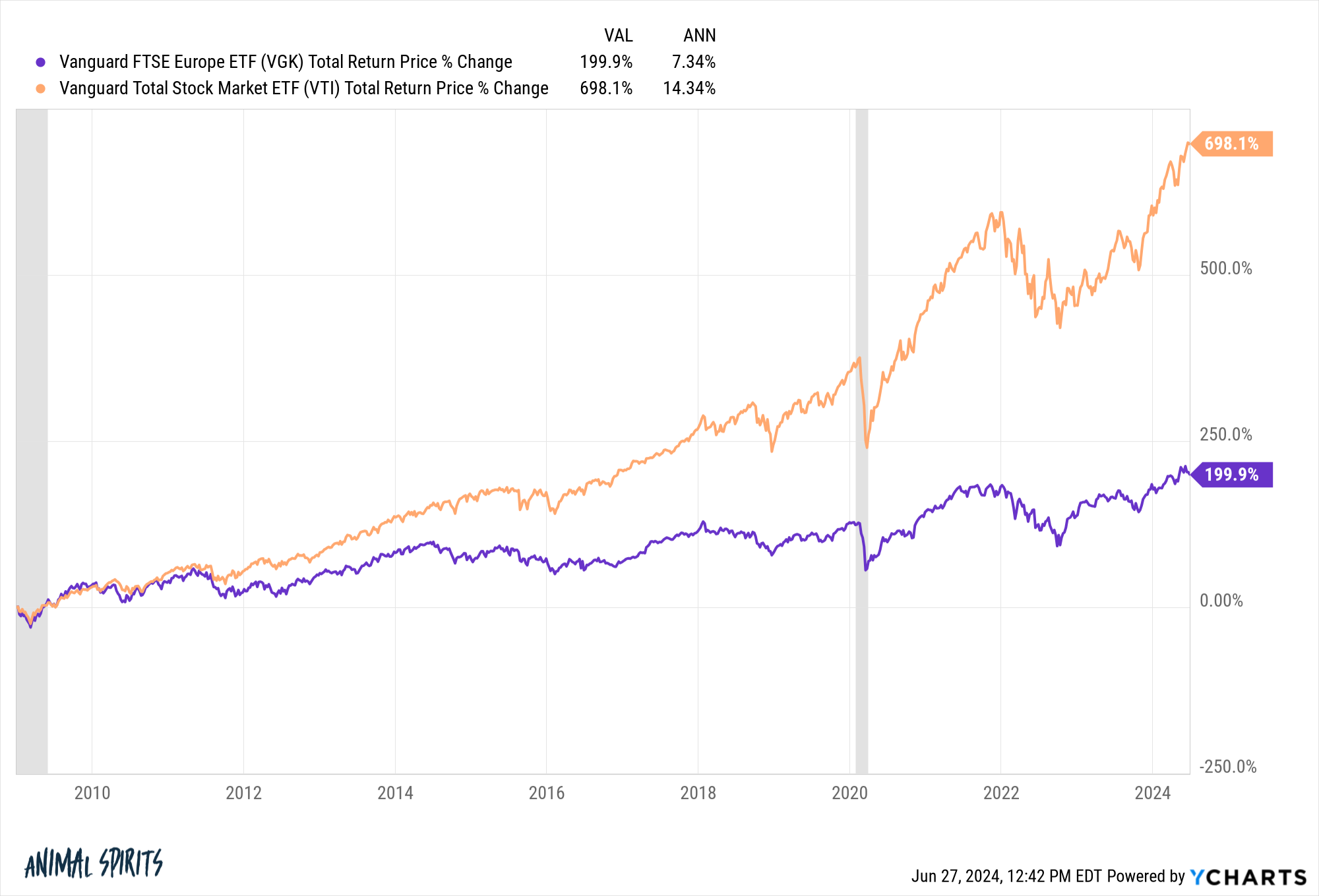

Here’s a look at European stocks versus the U.S. stock market since 2009:

To be fair, these numbers are from the perspective of a U.S.-based investor. A strong dollar has been a headwind for international stocks. The returns would look better for residents of European countries.

I’m not smart enough to give you all the reasons for this disparity or offer any broad-based solutions.1

The realist in me thinks the U.S. dominance will likely continue. We have the biggest and best tech companies in the world. We worship the stock market and economic growth in this country. Americans are also inclined to obsess over their jobs rather than take month-long holidays.

America has a lot of built-in advantages over the rest of the world.

But the contrarian in me thinks everyone is probably too pessimistic about Europe right now.

There’s a legendary story about how John Templeton started his investment career during World War II. The 26-year-old investor borrowed $10,000 in 1939, when the war began, and invested in more than 100 companies trading for less than $1 per share. A handful of those stocks turned out to be worthless, while the rest were wildly profitable.

Is this story a non-sequitur? Eh, maybe.

I know a lot of intelligent people in Europe. It’s hard for me to see growth continuing to collapse in the area while the United States swallows the world equity market. I suppose anything is possible. Being contrarian for contrarian’s sake is not an investment strategy.

There are two basic options:

Option 1. Europe is dead money. The rules and regulations there are too onerous for profitable corporations to flourish.

Option 2. Everyone is far too pessimistic about Europe’s prospects and it won’t take much good news to turn things around.

It’s at least a question worth considering.

Michael and I talked about European economic struggles and much more on this week’s Animal Spirits video:

Subscribe to The Compound so you never miss an episode.

Further Reading:

Long-Term Recency Bias

Now here’s what I’ve been reading lately:

- If I only had 12 months to live (Advisor Perspectives)

- The luxury of not caring (Fortune & Frictions)

- The last 72 hours of Archegos (Bloomberg)

- Being online is exhausting (Abnormal Returns)

- Europe is healthier than us (Walking the World)

Books:

1That would require a much longer post.