I don’t read much in paper form anymore. The bulk of my book reading is now done on a Kindle Paperwhite.1 Basically everything else I read is consumed on a computer, iPad or iPhone.

Yet I still have a soft spot for a few magazines. I have subscriptions to Esquire and GQ because I still enjoy the long profiles they do along with the $9,000 t-shirts in every picture. I had a subscription to Money Magazine but that was shut down this past summer.

That leaves my only finance/business publication as Fortune Magazine.

Fortune was founded by Henry Luce who also put out Time and Sports Illustrated. Fortune was founded in September 1929, which is the exact same month the Great Depression stock market crash began. It’s hard to believe the magazine survived that crash, let alone the next 90+ years.

I’m guessing print will slowly fade away over the coming years so I was happy when my first piece appeared in Fortune’s most recent issue.

I’ve been writing at Fortune’s website for a few months now and was asked to take one of the pieces I wrote there and re-do it for the magazine. So I worked with the editorial team there, re-wrote about half of the previous piece I submitted on how there’s always a bear market somewhere, re-wrote it a few more times following some back-and-forth, had them create some illustrations and charts and here we are.

Print may not have the same cache as it once did but I was still thrilled to have a piece appear in this staple of business publications. When I first began writing about finance seven years ago or so, I never would have imagined my work would appear in Fortune.

Here’s the piece for those who don’t have a subscription:

New highs in the stock markets are great for those who already own stocks. But there is a downside when stocks seemingly do nothing but rise. Any investor who’s been holding cash, waiting for lower prices and a better entry point, has had to keep waiting. And those deploying new savings into the markets have had to do so at higher and higher prices.

Those rising prices are also a catch-22 for long-term investors, because pricey markets today make impressive future gains less likely. The S&P 500 currently trades at about 30 times its average inflation-adjusted earnings over the past 10 years (the so-called CAPE ratio). Historically, levels anywhere near that high have almost always preceded periods of disappointing returns.

That’s why many investors are more comfortable buying shares when there’s blood in the streets. And the good news for those investors is that there will always be a bear market somewhere, even when the broad market is killing it. Three asset classes that have been left behind during this bull run stand out in particular right now in the eyes of bargain hunters:

Energy stocks

Oil prices topped $150 a barrel in June 2008. Since then, new production unleashed by the fracking revolution, combined with low inflation, has helped drive oil prices down by two-thirds—while hammering energy-company profits. Energy has been by far the worst-performing sector of the S&P 500 since mid-2008, and it’s not even close: The Energy Select Sector SPDR ETF (XLE) has fallen more than 13%, versus a gain of more than 200% for the S&P 500. One consolation prize is high dividends: XLE, for example, currently yields 3.8%, more than twice what the broader market yields.

Precious metals and mining stocks

These commodity-producer stocks often exhibit wild volatility because they’re unusually sensitive to economic growth and fluctuating supply and demand for the commodities themselves. Vanguard Global Capital Cycles (VGPMX), a mutual fund that’s a good proxy for the metals markets and related commodities, has done worse than just trail the market during this cycle: Over the past 10 years, the fund is down nearly 50%. (Again, relatively modest global growth is a culprit.) Investors often seek metals and mining stocks because they have a low correlation to the broader market, offering the benefits of a diversified portfolio. But sometimes owning uncorrelated assets means eating big losses while the rest of the market screams higher.

Value stocks

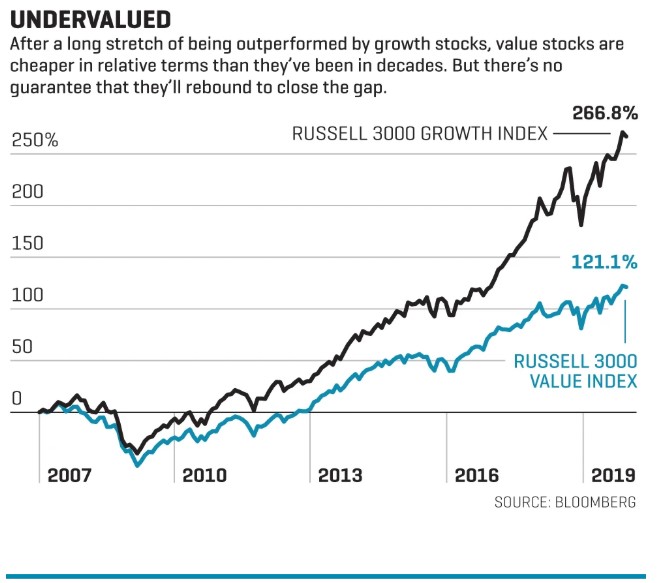

After the dotcom bubble deflated, value stocks—stocks that are cheap relative to the value of their underlying businesses—went on a run of huge outperformance over growth stocks. But growth has beaten the pants off value since the financial crisis (see graphic), led by high-growth companies such as Amazon, Netflix, Google, and Facebook that have monopolized investor mindshare. The growing economic impact of tech innovation, particularly in software; the rising value of intangible assets like patents, copyrights, and trademarks; and the willingness of investors to pay extra for growth in a world awash in capital have all contributed to growth’s edge.

Still, investors think a turning point could be near. Using a number of metrics, Cliff Asness, head of investment giant AQR Capital Management, showed in a recent piece that growth stocks are more expensive now than at any time other than the dotcom bubble. In contrast, Asness writes, “Excluding the tech bubble, the value of value is the cheapest it’s ever been.”

Of course, just because something is cheap doesn’t mean it can’t get cheaper. As our examples show, each of these categories has a black eye for a reason. That’s what makes the current situation for investors so confusing: It can seem like your only choices are to invest in assets with good fundamentals but high prices or to invest in assets with deteriorating fundamentals but low prices. Yes, history tells us that economic cycles will eventually boost energy and metals stocks and value stocks again, but it won’t tell us when.

The best move may be to worry less about “when.” Many investors (including my firm) favor a long-term strategy that involves broad diversification. In practice, that often means investing some capital in the areas of the market that have been hit the hardest, to take advantage of the cheap entry point. When deciding whether to wade into beaten-down asset classes, here are some lessons to keep in mind:

Nothing works all the time

Value investing has been repeatedly vetted by academics, professional investors, and the iconic Warren Buffett as an approach that works over the long term. But even sound investment strategies are bound to go through painful periods of underperformance. After all, the only reason any assets earn a premium over the rate of inflation is because owning them involves risks—and “sound” doesn’t mean “risk-free.”

Diversification means always having to say you’re sorry

The main reason to diversify is to avoid concentrating your money in a terrible-performing asset for an extended period. But spreading your bets also means that at least part of your portfolio will be sucking wind while the rest of it sprints ahead. You’re accepting the occasional strikeout to increase your odds of winning the game.

Don’t forget to rebalance

Diversification works only if you periodically rebalance your asset allocations. In essence, this means selling a little bit of what has done well to buy a little bit of what hasn’t. All of the asset classes above experienced strong returns before their fall from grace. Did you sell off a bit during the good times to bring them back to their target weights? If not, their losses have been even more painful for you—which could make it even harder to buy now, when strategy might dictate that you should.

This piece originally appeared in Fortune Magazine. Re-printed here with permission. Web version here.

1It took me a while to get used to this but now I love it. I can switch between multiple books if necessary and the highlighting feature is very useful for someone who writes a lot about what they’re reading.