A reader asks:

I have a stock market theory. The large amount of cash in money markets, HYSAs, etc. means that a “down” day/days for the stock market will quickly be reversed by buying the dip. And this will continue until cash balances drop significantly. Thoughts?

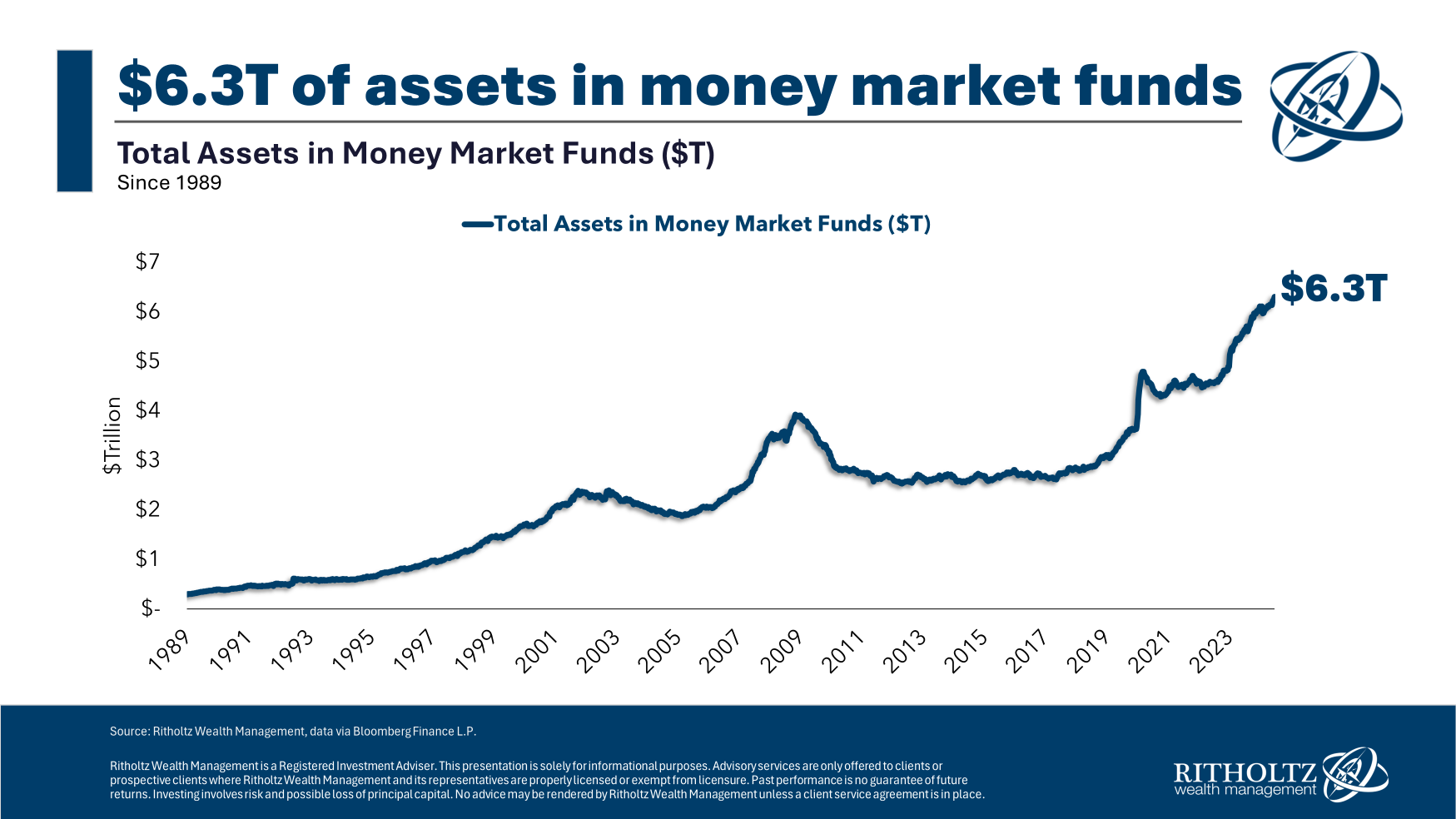

There is a lot of cash sitting in money market funds right now:

That’s $6.3 trillion, which is nearly double the amount that was in these funds pre-pandemic.

It makes sense. The Fed jacked up short-term interest rates. You can get in excess of 5% in these funds. Long-duration bonds carry much higher interest rate risk and got crushed when rates rose. These are short-term debt instruments that don’t go down in value on a nominal basis.

Money market funds have been a win-win for investors who needed some mix of yield, volatility protection and liquidity these past few years.

But what happens when the Fed starts cutting rates?

Yields on money market funds will fall. It’s possible the Fed could cut rates rather quickly. Those 5% yields could turn into 2-3% yields in a relatively short period of time if inflation keeps falling, the economy slows even further or some combination of the two.

It’s a fair question to ask whether this cash on the sidelines will provide a buffer to falling stock prices.

Let’s start with some quantitative analysis before going into the more qualitative aspects of this theory.

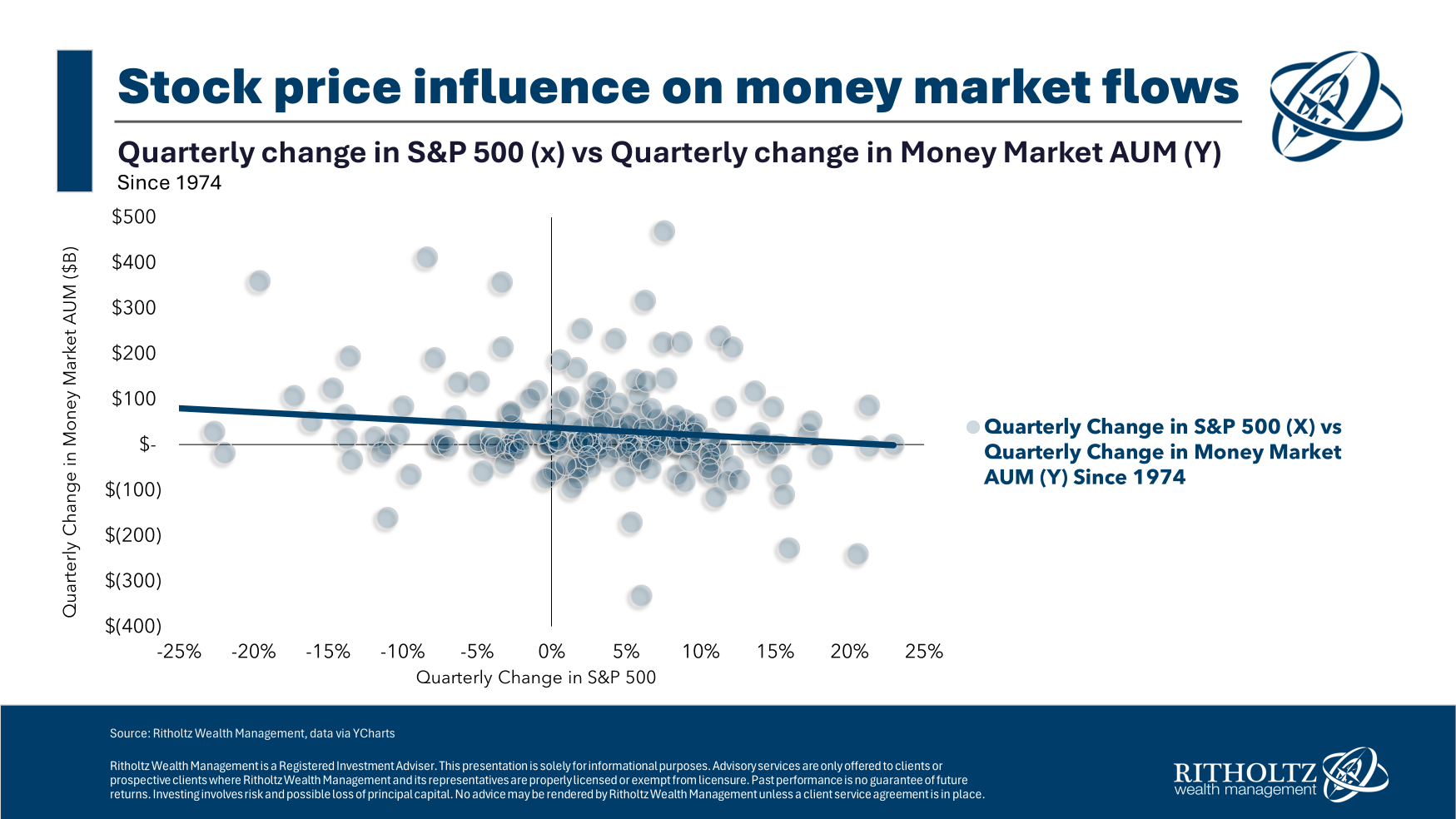

The Federal Reserve has quarterly data on money market assets going back to the mid-1970s. I looked at the change in quarterly money market assets and the corresponding quarterly return on the S&P 500.

It was hard to find much of a strong relationship one way or another:

To test this theory, I looked at the returns in the down quarters for the stock market to see if it impacted money market flows. You were more than twice as likely to see assets flow into money markets in a down quarter than out of money markets.

So it’s not like investors have used money market funds as a form of cash on the sidelines in the past.

But what about yields?

We are heading into a rate-cutting cycle. Does cash flow out of money market funds as yields fall?

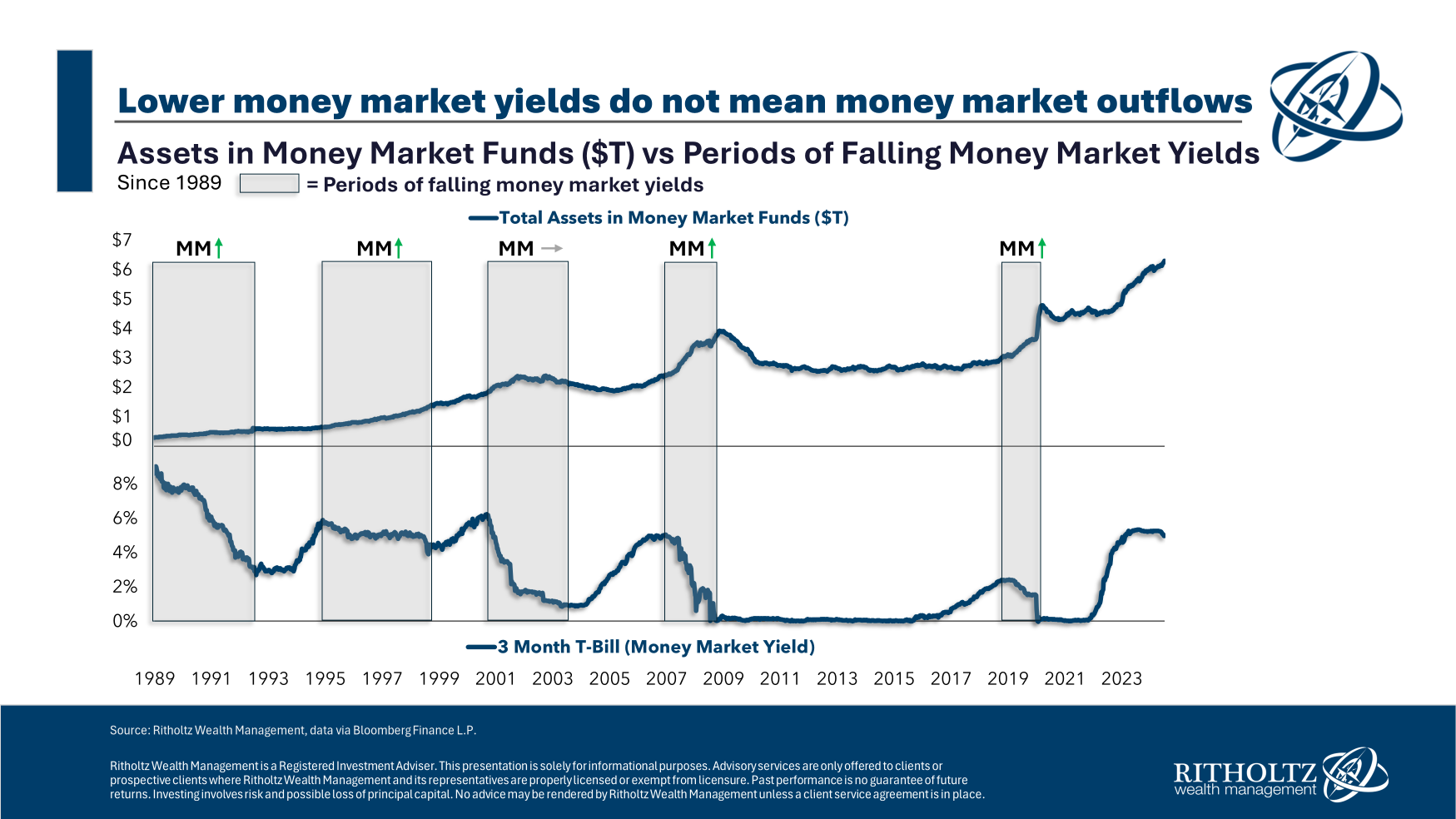

Not necessarily. Here’s a look at assets in money market funds versus yields:

The falling rate environments are highlighted on the chart. From 2005-2009, yields fell but assets in money markets went skyward. The same thing happened during the pandemic.1

So while it would be nice to assume investors would be chomping at the bit to put cash to work during a down market, the opposite is more likely. People get scared when stocks are falling and put more money in cash.

Will that happen the next time stocks fall?

We shall see.

It’s also worth pointing out money market funds only date back to the mid-1970s. Here’s a quick history lesson I wrote about these funds in a previous piece:

Vanguard is synonymous with index funds but it was money market funds that carried Jack Bogle’s company in the 1980s because interest rates were so high.

Banks used to be capped on the amount of interest they could pay. Then the first money market fund came along that allowed people to put their money to work with a bank through prevailing interest rates.

By 1981, Vanguard held just 5.8% of mutual fund industry assets. That number dropped to 5.2% by 1985 and 4.1% by 1987. Their most popular fund series, the Wellington Funds, saw 83 consecutive months of outflows.

During the 1980s, mutual fund assets jumped from $241 billion to $1.5 trillion. The charge was led by money market funds, which soared from $2 billion to $570 billion, accounting for almost half the increase.

So it’s hard to pinpoint how much the stock market impacted the flows because they were a new fund category in the 1970s and 1980s.

The other part of the equation is how much of the boost in money market funds came from bonds or other sources of fixed income?

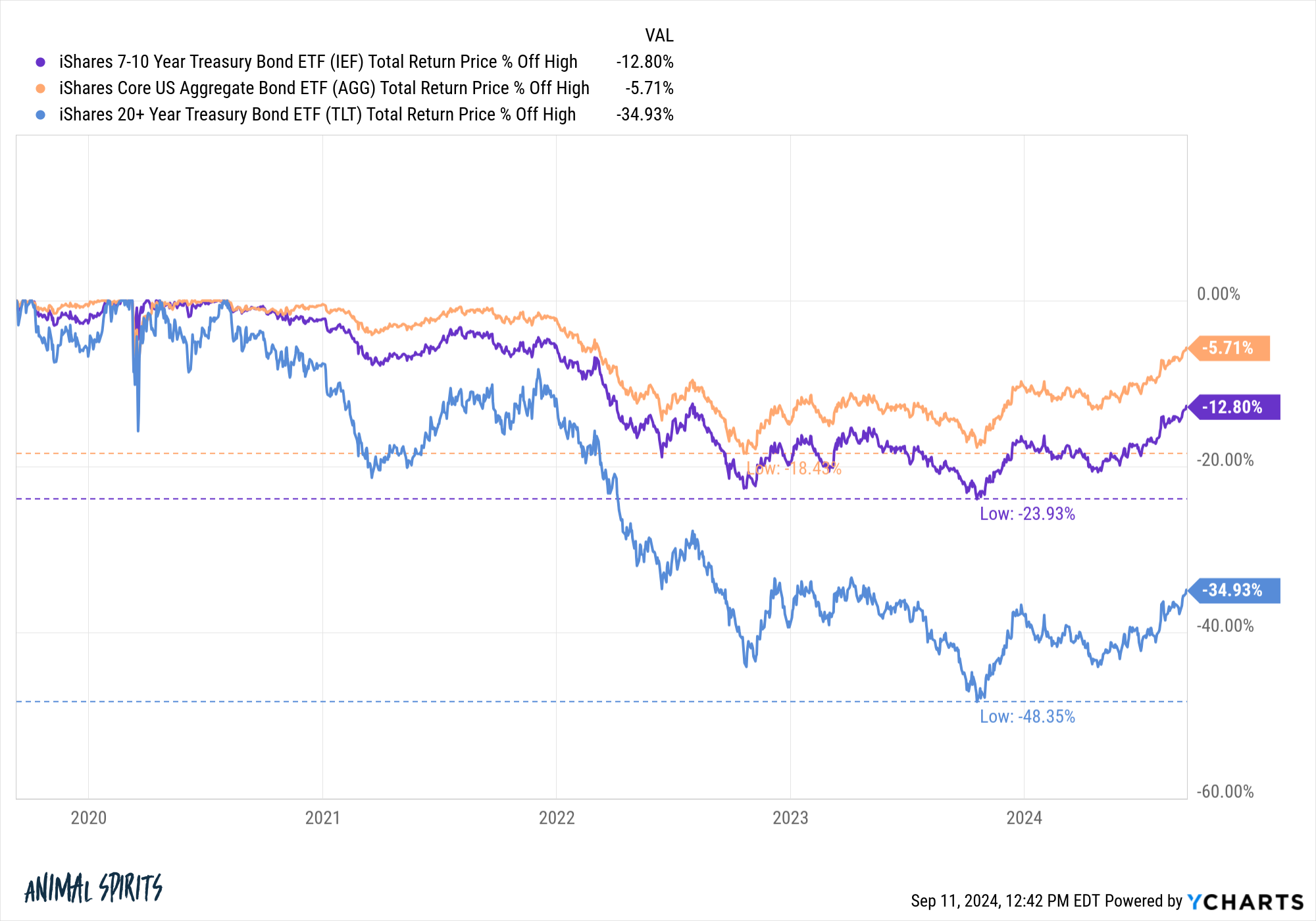

Bonds just experienced their worst bear market in history:

Surely some portion of the trillions of dollars that flowed into money markets came from bonds.

When money market yields fall, there is probably a stronger case to be made for that money to go into bonds than stocks since cash can act as a form of fixed income.

Plus, there is a baby boomer retirement aspect of the allocation question. Millions of baby boomers are already retired. Millions more will be retiring over the course of this decade. Most retirees de-risk a portion of their portfolios in retirement because they don’t want/need as much volatility.

What if some of these assets are sticky?

It’s certainly a possibility.

So while some of that cash on the sidelines could find its way into the stock market, I wouldn’t bet on the idea that money market flows will save the stock market when it falls.

I covered this question on the latest edition of Ask the Compound:

Our resident estate expert, Taylor Hollis, joined me on the show this week to discuss questions about CD rates, how trusts work, how to protect your finances from an illness in the family and paying off student loans with a 401k loan.

Further Reading:

How Individual Retirement Accounts Changed the Stock Market Forever

1Assets did fall and then stagnated coming out of the Great Financial Crisis but that was a period with years of 0% yields. I’m actually surprised assets didn’t fall further in the 2010s.