A reader asks:

So I work in Tech at a company whose name ends in dot ai and there is all this talk of the AI bubble and how VCs have quickly moved from Crypto to AI, not to mention all the buzz around ChatGPT. Question is – can you have a bubble in a high rate / rising rate interest environment or do we need low rates / easing Fed as a precursor to any bubble?

Is it possible for AI to do everything the technology pundits are predicting and not turn into a bubble?

I don’t think so.

Most bubbles start out as a wonderful idea or invention that people simply take too far as they overestimate the investment implications of new technologies.

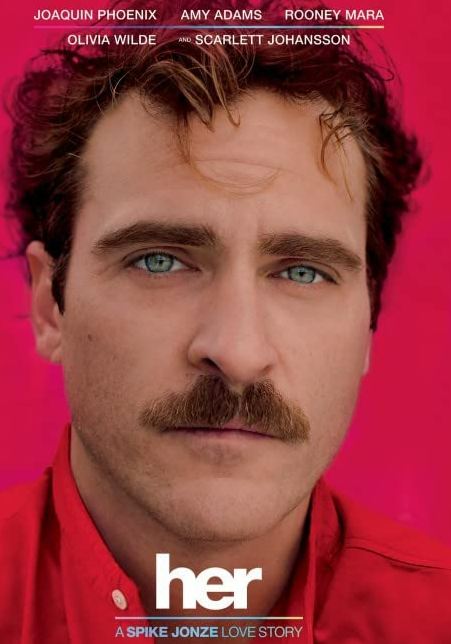

If we truly are on pace to have Scarlett Johansson as an artificial intelligence personal assistant in our ear like in Her then we are probably going to have an AI bubble at some point.

Even if AI lives up to the hype, we’re likely going live through a boom and bust before we get there.

We got everything we were promised and more out of the internet but not before going through the bursting of the dot-com bubble first.

But is it even possible to get a bubble with interest rates now at 5% and potentially going higher?

Yes it is.

I’m not saying we will but interest rates aren’t the sole cause of bubbles, much to the chagrin of the Fed haters of the world.

There have certainly been market environments where low interest rates and easy monetary policy added fuel to the fire.

But there are plenty of examples where people lost their minds without the help of central banks or low interest rates.

In 1920, Charles Ponzi created the scheme that now bears his name.

Short-term interest rates were 5% at the time but that didn’t really matter when Mr. Ponzi was promising investors 40-50% every 90 days.

Here’s what I wrote in Don’t Fall For It:

Despite his shady financial background, Ponzi opened up a firm called the Securities and Exchange Company to raise money from investors. The pitch to clients was just a tad ambitious. Prospective investors were promised 40% on their original investment after just 90 days! That’s not bad considering the prevailing interest rate at the time was just 5%. Forty percent every three months would be an annualized return of almost 285%. Earning 57 times the risk-free interest rate is a pretty good deal if you can get it. Even more investors gave Ponzi money when he upped the ante by offering 90-day notes that would double your money or 50-day paper that would give investors a 50% return on investment.

Interest rates don’t matter when you convince yourself you can earn life-altering returns.

In the Roaring 1920s the Dow rose 500% from 1922 through the fall of 1929. The 10 year treasury yield averaged 4% in that time, never going above 5% or below 3.3%.

The 1920s ushered in automobiles, airplanes, radio, assembly lines, refrigerators, electric razors, washing machines, jukeboxes and more.

The explosion in consumer spending and innovation was unlike anything we’ve ever seen. Plus, people wanted to move on from World War I and the 1918 Spanish Flu pandemic.

No one needed interest rates to spark a fury of speculation and excess. Human emotions did just fine on their own.

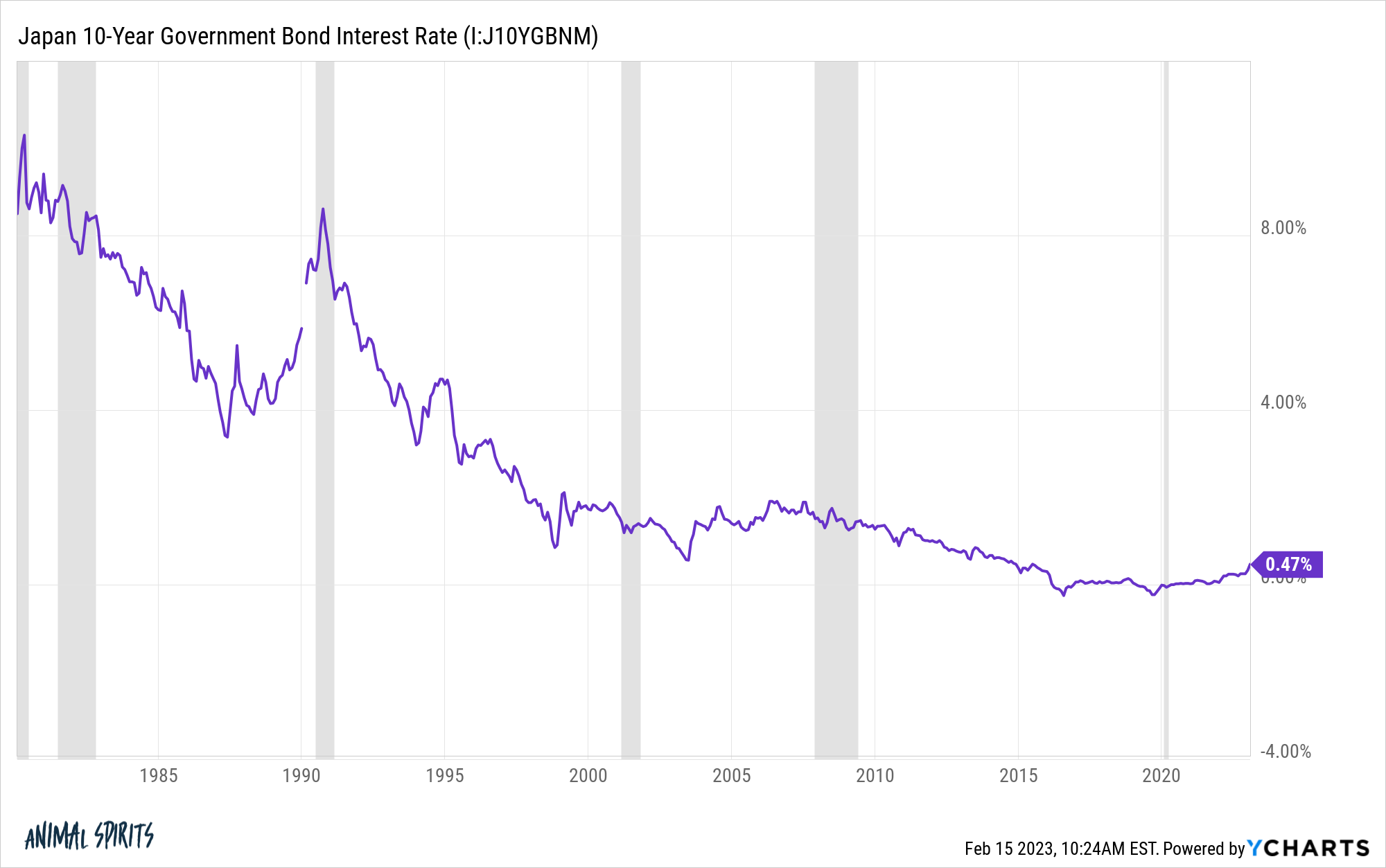

Japan’s financial asset bubble in the 1980s is arguably the biggest in history.

In the 1980s, Japanese stocks were up almost 1200% in total or nearly 29% per year. And that’s after they had already run up 18% annual gains during the 1970s.

At the height of the bubble in 1990, Japan’s property market was valued at more than 4x the real estate value of the United States despite the fact that the U.S. is 26x bigger.

Interest rates were probably higher than you would have expected during this ridiculous increase in prices.

In the 1980s interest rates on Japanese government bonds averaged 6.5%. Since 1990 they have averaged 1.8%. This century the 10 year yield in Japan has averaged just 0.85%.

There has been no bubble in Japan with rates averaging less than 1% for more than two decades. One of the biggest asset bubbles in history occurred when rates averaged more than 6%.

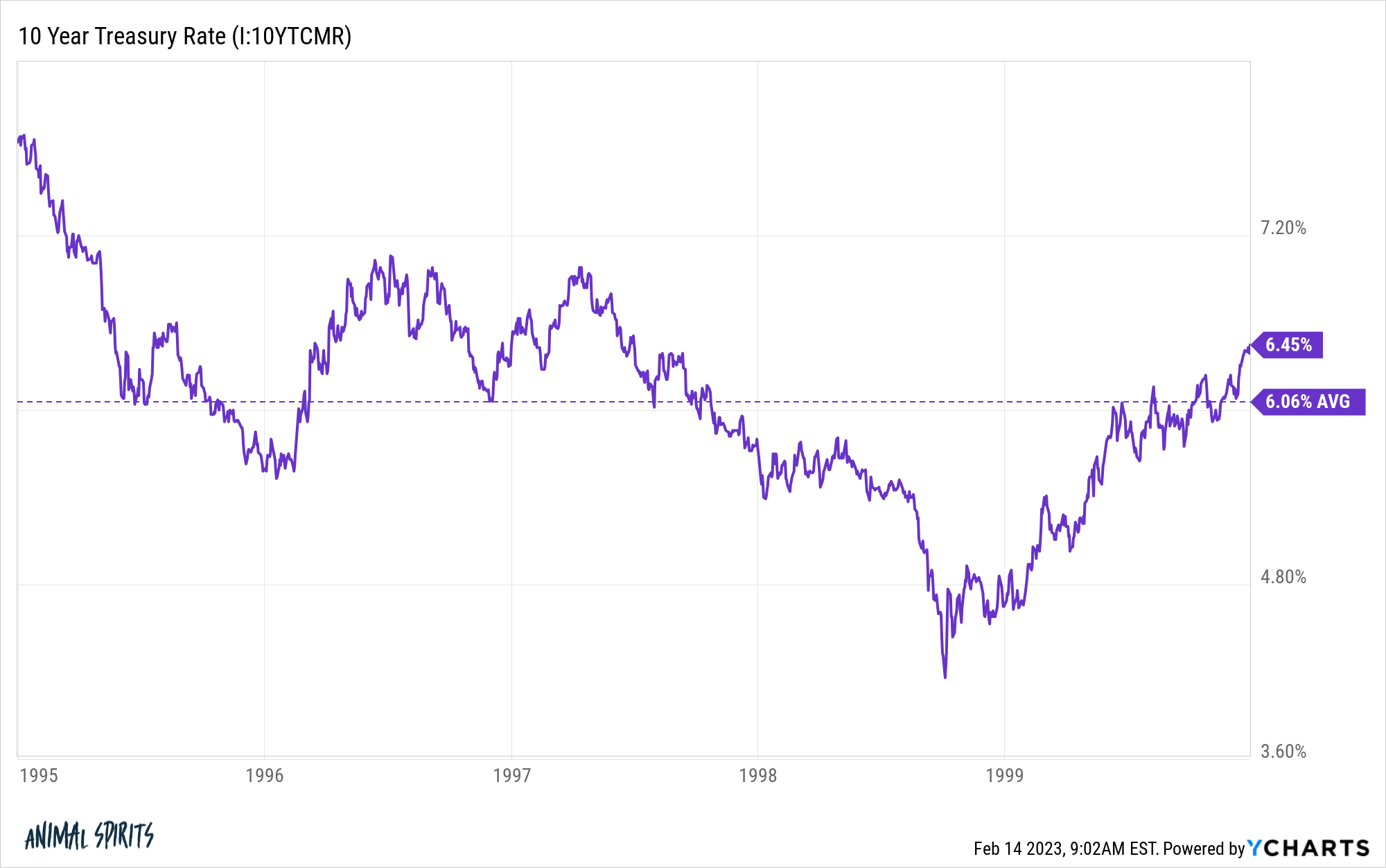

Yields were similar in the U.S. during the dot-com bubble:

Ten year treasury yields averaged more than 6% from 1995 to 1999. The Nasdaq compounded at more than 40% per year in that time.

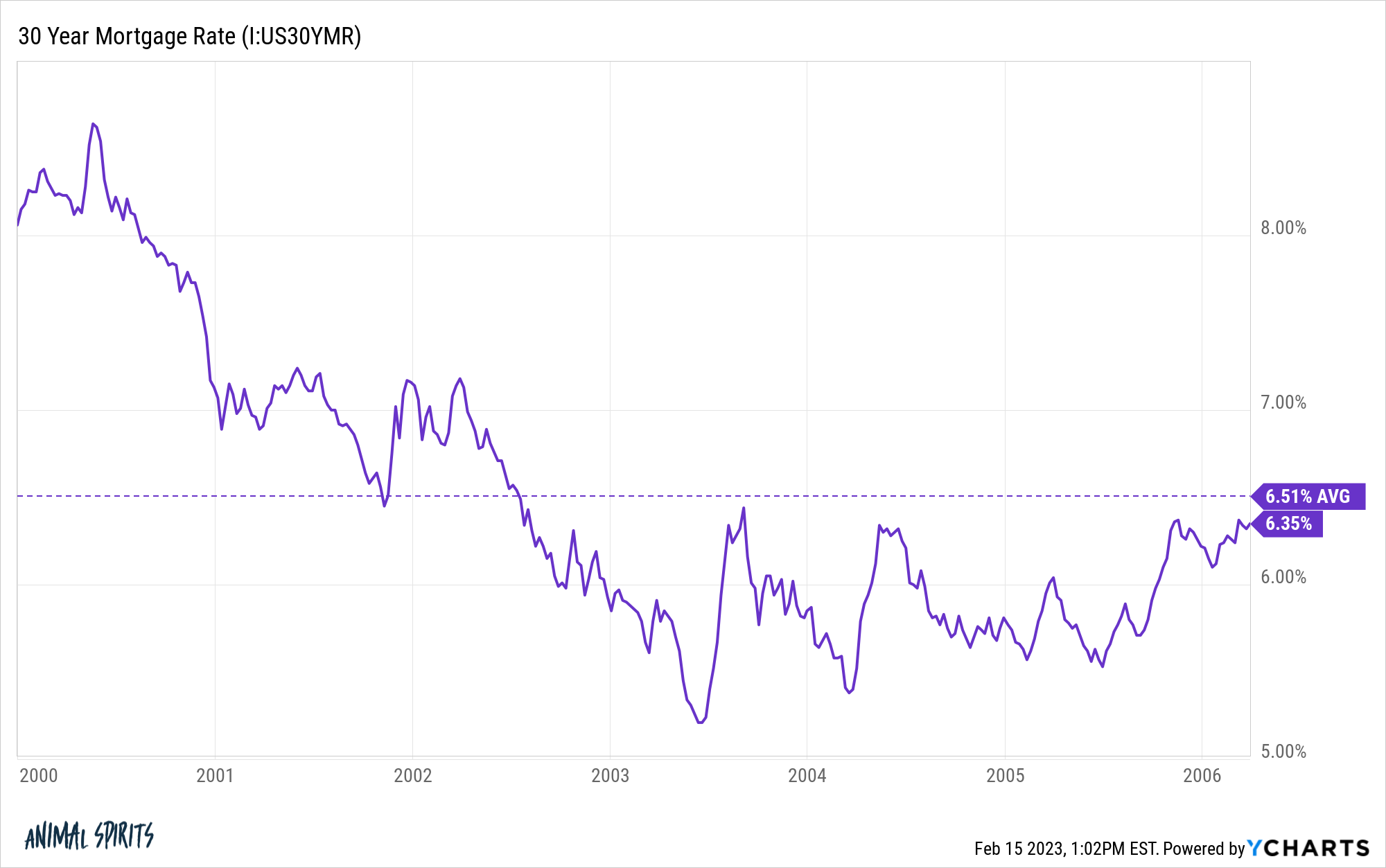

Japan has avoided another bubble since the 1990s but we didn’t waste much time after the tech boom was over in the United States. The housing bubble of the aughts took off just a few short years after the dot-com bubble popped.

Housing prices nationwide were up 85% from 2000 through the spring of 2006.

Mortgage rates averaged 6.5% in that time and never came close to falling below 5%:

That period of excess had more to do with lax lending standards and subprime mortgage bond shenanigans from the banks than interest rates. Credit standards mattered more than the level of mortgage rates.1

Obviously, low rates had a lot to do with the excess we saw during the pandemic in 2020 and 2021. But rates were low for the entire decade of the 2010s and we saw nothing like the meme stock craze or housing gains that occurred in the 2020s.

Low rates do provide a breeding ground for speculation to occur but there have been plenty of instances in the past when we lost our collective minds bidding up the prices of financial assets without them.

As Charles Mackay once wrote, “Men, it has been well said, think in herds; it will be seen that they go mad in herds, while they only recover their senses slowly, and one by one.”

This will continue to happen when new and exciting things happen in the world, regardless of monetary policy.

Further Reading:

Why Bubbles Are Good For Innovation

1There were plenty of people who took out adjustable-rate loans with low teaser rates, but those loans never should have been given out in the first place. It was poor lending standards and re-packaging of crappy bonds that were the problem.