In the 1970s, researchers at Corning Glassworks developed an astonishingly clear type of glass. Scientists at Bell Labs took the fibers from that glass and sent laser beams down the length of the fibers, using optical signals which worked much like computer coding with zeroes and ones.

Mashing these two seemingly unrelated inventions together — clear glass with fibers and lasers — created what is now known as fiber optics. Fiber optic cables are more efficient at sending signals over long distances than the original copper cables used in the past. The Atlantic Ocean has 10 different fiber optic cables which easily carry the bulk of our data and voice communications around the globe instantaneously.

These cables are being used to transmit the information we consume every day on the little glass supercomputers we carry around in our pockets for work, play, entertainment, socializing, and wasting time.

It’s highly likely that the infrastructure for this system would have taken a lot longer to put in place if it wasn’t for the dot-com bubble of the 1990s.

The dot-com bubble certainly led to plenty of madness and eventual losses as speculators tried to make sense of how far technological innovation could take things in the “New Economy.”

Intel, Cisco, Microsoft, and Oracle, some of the biggest tech darlings of the 1990s were worth a combined $83 billion at the outset of 1995. Just five short years later, as the tech bubble inflated to astronomical proportions, this group had grown to a combined market cap of nearly $2 trillion.

In 1999 alone 13 tech stocks were up 1,000% or more, including the biggest winner of them all Qualcomm, which rose an astonishing 2,700%.

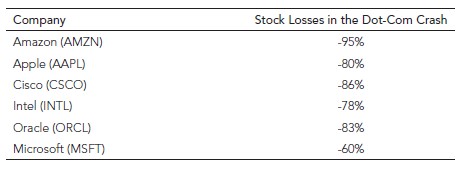

The bubble finally popped in early-2000 when investors realized the fundamentals of these businesses couldn’t possibly live up to the insane growth in their share prices.

Too much competition for investment, overcapacity, and lofty expectations during a bubble can lead to enormous losses for those left holding the bag when the bubble eventually pops.

But if some of that investment is used for productive purposes, it can lead to net gains for society when it’s put to productive use. Before the dot-com bubble popped, telecom companies raised almost $2 trillion in equity and $600 billion in debt from investors eager to bet on the future.

Those companies laid down more than 80 million miles of fiber optic cables, which represented more than three-quarters of all digital wiring installed in the U.S. up to that point in all of history. There was so much overcapacity from this buildout, 85% of these fiber optic cables were still unused as of late-2005. Within four years of the end of the dot-com bubble, the cost of bandwidth had fallen by 90%.

So despite more people coming online by the day during this period, costs fell and there was so much capacity available that those who were left standing were able to build out the Internet as we know it today.

The dot-com bubble laid the tracks for the Internet as we know it today.

The British Railway Mania

A similarly positive outcome came during one of history’s most underappreciated bubbles — the railway mania of the 1800s.

Like most bubbles, it started out as a good idea that was simply taken too far by investors.

The first commuter trains appeared in the United Kingdom during the 1820s. They traveled just 12.5 miles per hour which reduced the trip from London to Glasgow to 24 hours. The Railway Times asked, without even a hint of sarcasm, “What more could any reasonable man want?”

The first railway mania hit in 1825 with the opening of the first steam railway. An economic downturn snuffed out any speculation and by 1840, there were 2,000 miles of track completed which led some to speculate whether the national railway system in Britain was already finished.

Memories are short when people think there’s money to be made so this first mini-mania in railway stocks became a distant memory by the summer of 1842. That’s when Prince Albert of the Royal Family persuaded Queen Victoria to make her first train ride. That was the all-clear investors needed to hop aboard the train that was railway stocks. By 1844, investors viewed railway stocks as safe and secure was with huge upside potential. It didn’t take long for that cautious optimism to morph into reckless euphoria.

Nearly 500 new railway companies were in existence by the summer of 1845, with stock prices in the sector up a cool 500%.

Money was flowing into these projects faster than Usain Bolt with the wind at his back.

By June 1945 the Board of Trade was considering over 8,000 miles of new railway, which was four times more than the existing system and almost twenty times the length of England. There were literally plans for tracks that started nowhere and went nowhere with no planned stops along the way.

And it’s not like it was the British government investing in the infrastructure of the country. No, it was investors who were looking to get rich in a hurry. The media became heavily involved in this mania, pumping railway companies and projects on a daily basis so the public at large became by far the biggest investors in the mania.

The British Parliament published a report in the summer of 1845 revealing the identity of 20,000 investors who had subscribed for at least £2,000 or more worth of railway stocks, including 157 members of Parliament, 260 clergymen, Charles Darwin, John Stuart Mill, and the Bronte sisters.

The rest were mostly regular people, showing how broad the speculation was. Many investors were subscribed for more shares than they could ever hope to pay for but the idea was they would all have the chance to sell at a premium before getting all of their capital called to create the actual railway projects.

By 1850, the amount invested was around £250 million, almost half the GDP of Great Britain at the time, the equivalent of roughly $1.4 trillion for the UK today (or almost $10 trillion for the U.S. in today’s terms).

Increased competition and overinvestment finally brought these companies back to earth. Bankruptcies hit an all-time high in 1846, just a year after the height of the mania. People from all walks of life and levels of wealth were ruined. By the start of 1850, railway share prices had fallen an astronomical 85% on average.

The Silver Linings Playbook From a Bubble

A large number of tech start-ups with seemingly good ideas went out of business after the dot-com flameout.

But that era planted the seeds for the next wave of innovation that occurred, which gave us services like YouTube, Facebook, Twitter, Airbnb and Google. Venture capitalist Marc Andreessen once observed, “All those ideas are working today. I can’t think of a single idea from that era that isn’t working today.”

The railway boom and bust had some positive outcomes as well. Not all was lost from this period of untamed speculation, greed, and accounting fraud. By 1855, there were over 8,000 miles of railroad track in operation, giving Britain the highest density of railroad tracks in the world, measuring seven times the length of France or Germany.

The railways set up during the bubble years came to represent 90% of the total length of the current British railway system. People and businesses across the country experienced massive gains in efficiency through cheaper and faster transportation of raw materials, finished products, and passengers.

And during the 1840s more than half a million people were employed by the railway companies to make those tracks a reality. In many ways, this was a wealth transfer from rich and middle-class speculators to the labor class that simultaneously provided the country with much-needed transportation infrastructure.

News distribution spread and the capital markets became more mature. New stock markets were set up in cities all over the country. Stock brokerage firms grew from 6 in 1830 to nearly 30 by 1847. There was greater innovation during the industrial revolution of the 18th century but the railway boom required far more capital, and thus investors, so this changed the way the middle class invested their money.

The problem for those trying to handicap the financial ramifications for these types of innovations is investors become exceedingly impatient when new technologies hit the market.

The promises of the Internet almost all came true, but we first had to go through the crash and a number of lean years to get there.

It took time for the combustion engine to completely replace the horse and carriage. Most of the early car companies flamed out. As car ownership first took off in the 1920s there were 108 automakers in the U.S. By the 1950s, they were whittled down to the big three that produced the majority of cars. The entire airline industry basically lost money or went out of business in the century after air travel was invented.

There are certainly pockets of bubbles in the markets right now. Many of those sectors will see certain companies get destroyed.

But the leaps forward we may experience from things like electric vehicles, other clean forms of energy, healthcare and technological innovation in the home and workplace could benefit society for years to come.

Some people create life-changing levels of wealth during manias. Others lose their shirt when the bubbles pop.

Yet all bubbles are not bad in and of themselves.

The silver lining from a bubble is society often benefits from the sheer amount of money that pours to invest.

*******

This piece was adapted from my book Don’t Fall For It: A Short History of Financial Scams.