Inflation is finally slowing down.

We’ve gone from an annual run rate of more than 9% to around 7%.

This is not yet mission accomplished but the fact that we’ve gotten a handful of inflation prints going in the right direction is a good start.

Even though the past 3 months of inflation have come in at an annualized rate of 3.7%, the Fed is not impressed.

Jerome Powell and team want to get it to a more reasonable level. They say that’s 2%.

Where does their 2% inflation target come from? You would have to ask them.

When asked this week if they would consider changing that target, Powell emphatically said nope, nada, no, not gonna happen:

That’s just — changing our inflation goal is just something we’re not — we’re not thinking about, and it’s something we’re not going to think about. It’s — we have a 2 percent inflation goal, and we’ll use our tools to get inflation back to 2 percent. I think this isn’t the time to be thinking about that. I mean, there may be a longer run project at some point. But that is not where we are at all. The Committee, we’re not considering that. We’re not going to consider that under any circumstances. We’re going to — we’re going to keep our inflation target at 2 percent. We’re going to use our tools to get inflation back to 2 percent.

At this point, I’m not sure if the Fed actually believes this or if they just don’t want markets to take off before getting inflation a little more under control.

Time will tell.

If they are serious about that 2% inflation target, history says it might not be as easy as they think.

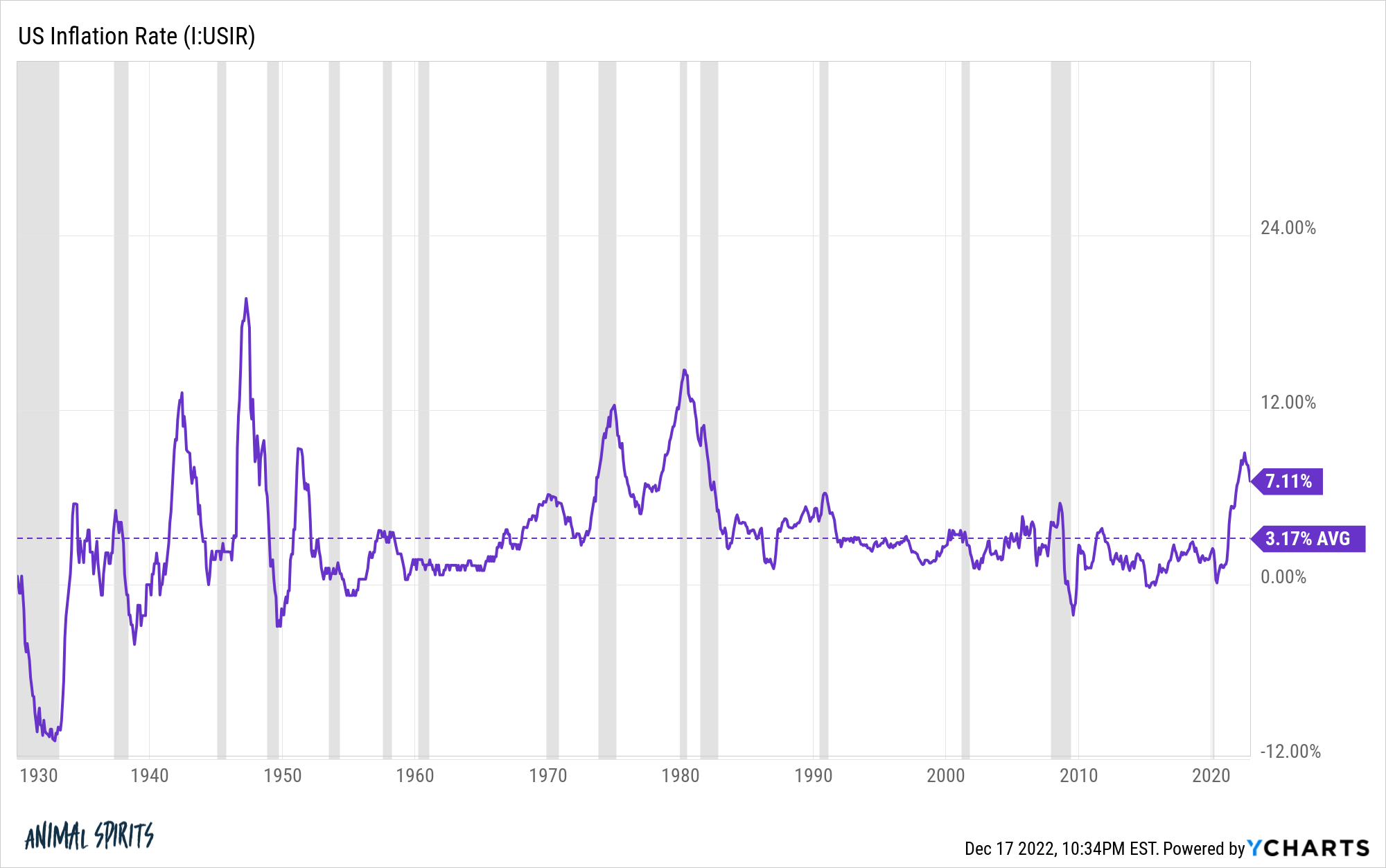

Over the past 90+ years, the average inflation rate in the United States has been a little more than 3% per year:

The problem is there is a wide variation around that long-term average. The Fed may have a target in mind but inflation itself is a moving target.

This is the way averages work but it’s interesting to note that since 1930, the annual inflation rate has come in between 1% to 3% just 39% of the time.

That means more than 60% of the time inflation has been below 1% or more than 3%.1

The Fed’s target inflation rate has been in the minority of historical economic environments in this country.

And even if the Fed is able to get back to target, they’re likely going to have to be patient to get to that place.

One of the reasons it’s so difficult to handicap a highly inflationary environment is because there are so few historical precedents.

Everyone of a certain age points to the 1970s as the inflationary bogeyman. No one who lived through that wants a repeat of that period.

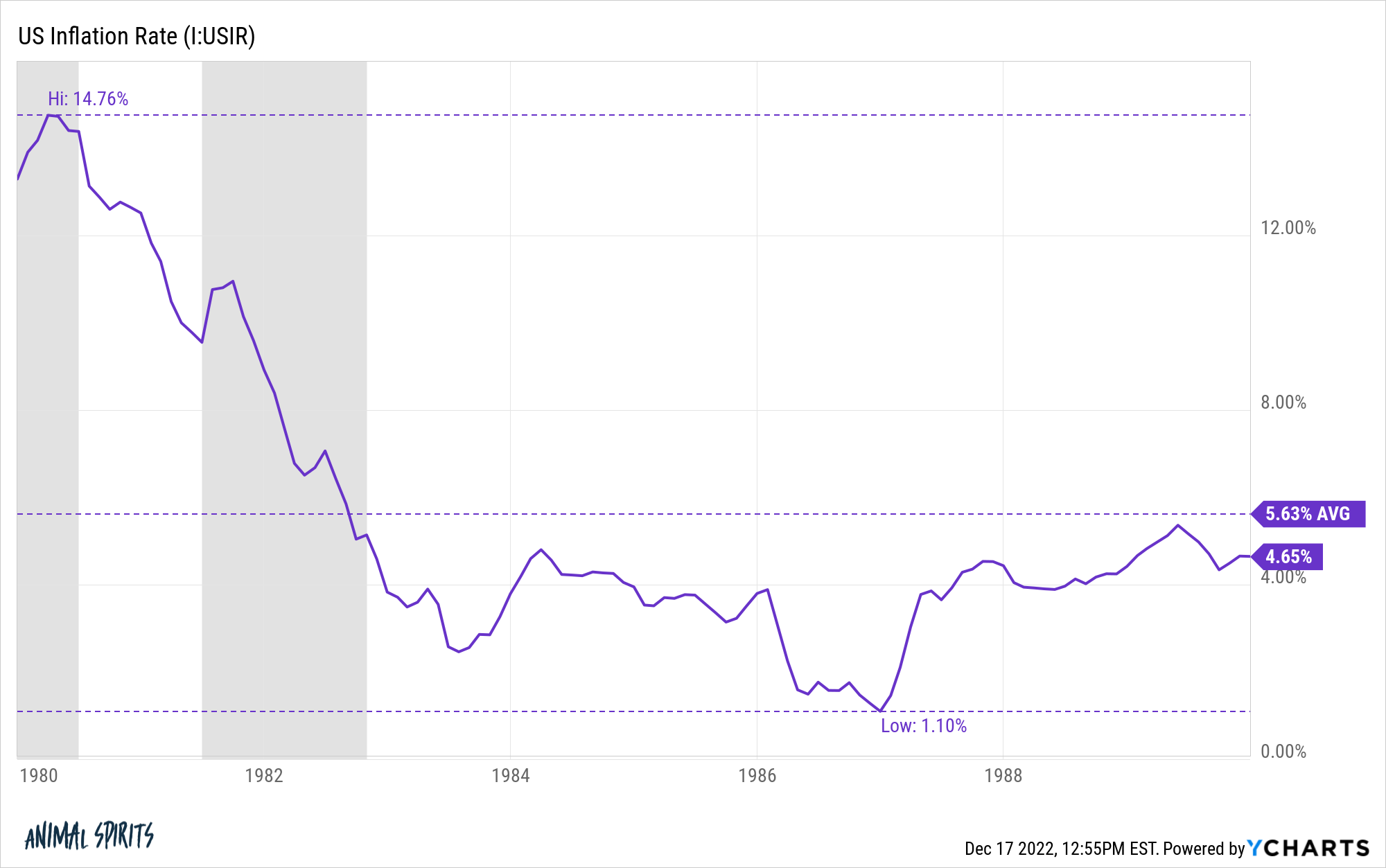

While the Paul Volker-led Federal Reserve did snuff out the double-digit inflation of the late-70s and early-80s, it took a long time for inflation to hit the Fed’s current target:

Inflation was coming down from a much higher level back then but after peaking at nearly 15% in 1980, inflation didn’t go below 3% until 1983.

It didn’t go below 2% until 1986.

In fact, inflation was 4% or higher for nearly 60% of the 1980s. It was only 3% or lower for just 14% of the decade.

The 1980s had relatively high inflation and the economy and stock market did just fine.

It was a disinflationary environment but certainly not a low-inflation environment.

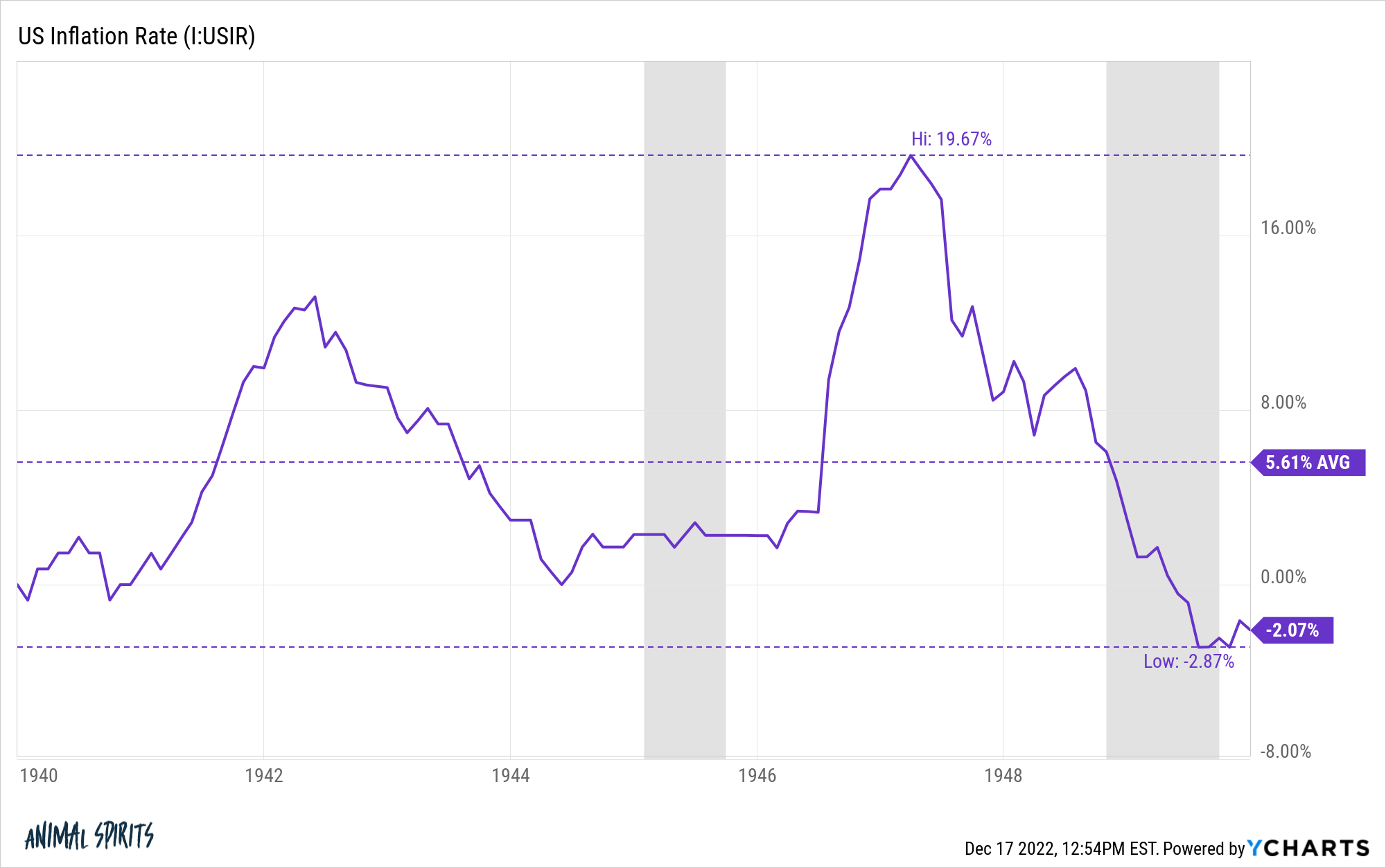

The only other time besides the 1970s when we experienced severely high inflation in modern economic times was in the 1940s:

The 1940s might be one of the wildest decades on record when it comes to price stability (or lack thereof).

World War II had a lot to do with that obviously.

The decade started out with inflation basically at 0%. It quickly shot up to double-digit levels, hitting upwards of 13% by the spring of 1942.

The change in prices slowed considerably from there but it took 19 months for the annual rate to fall below 3%. It was almost two full years before inflation fell below 2% annually.

Inflation remained relatively calm in the final years of the war but the post-war boom sent prices skyrocketing.

People were more used to the boom-bust cycle of inflation-to-deflation and back again following war times but the inflation in this period was no joke, hitting nearly 20% by the spring of 1947.

No one looks back at this as a time of economic pain mainly because people were so happy the war was over but the inflation from that timeframe didn’t leave long-lasting scars.

It was a boom time in the U.S. economy in the late-1940s through the 1950s even with a handful of minor recessions along the way.

Inflation crashed yet again from those nosebleed levels but it took almost two years to hit 2%.

And inflation didn’t simply stabilize at that rate once it got there. The 19.7% peak inflation ended in deflation which lasted for more than a year.

Then there were 14 consecutive months of declining inflation prints (meaning deflation) from the spring of 1949 through the spring of 1950.

A sample size of two isn’t enough to draw concrete conclusions. It’s certainly possible inflation will fall faster this time around.

However, it makes sense that it would take some time for inflation to fall. The U.S. economy is so large and dynamic that it’s difficult for it to change course on a dime.

The Fed sounds serious about hitting its 2% target but it’s likely not going to happen overnight.

They’re either going to have to be more patient or risk sending us into a deflationary spiral if they go too hard with interest rate hikes.

I remain firmly in the camp of trying to avoid a recession if at all possible and being patient when it comes to inflation.

Hopefully the Fed understands patience is a virtue.

Further Reading:

Why Today’s Inflation is Not a Repeat of the 1970s

1Below 1% around 17% of the time and above 3% in 44% of all inflation readings.