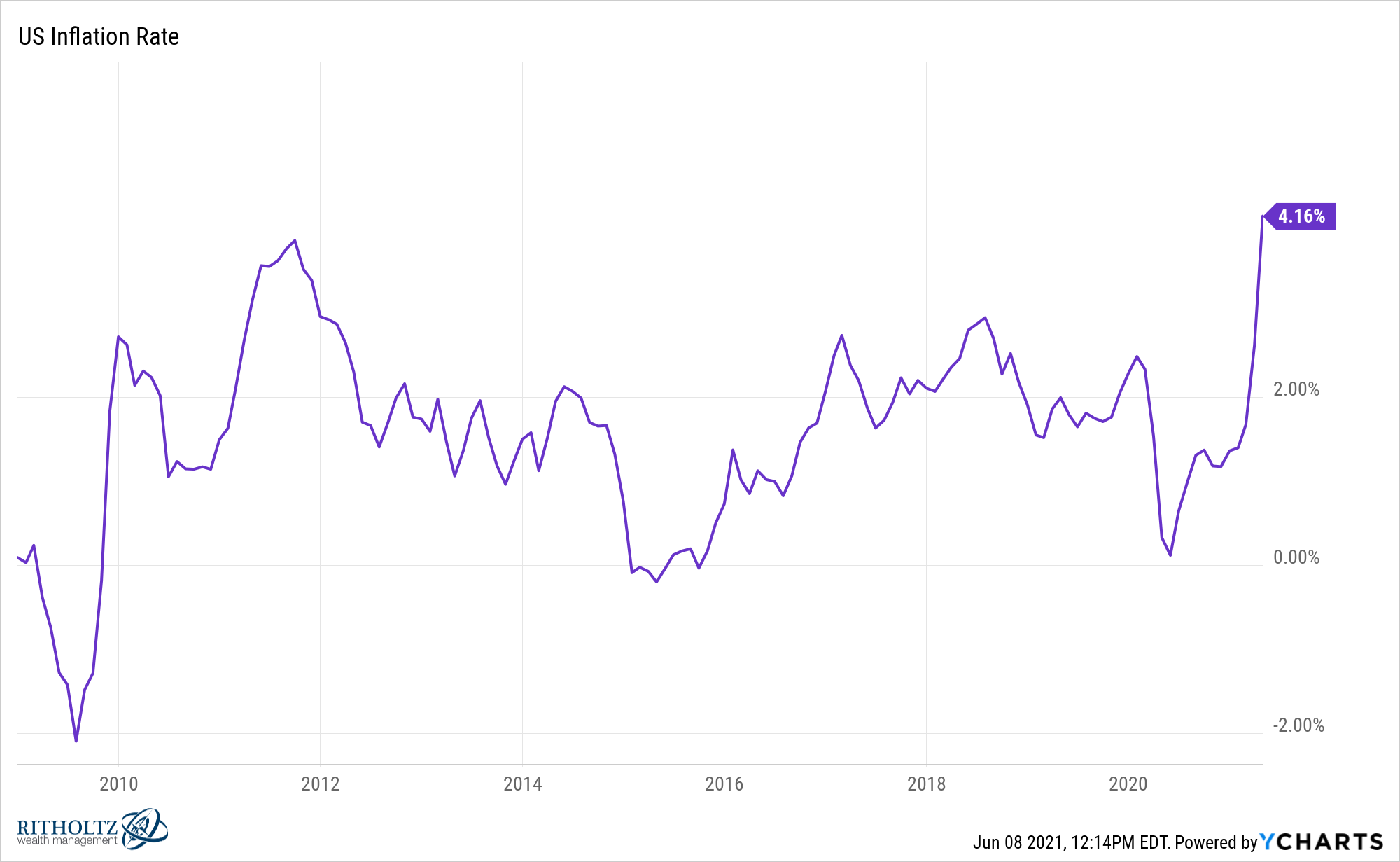

Inflation is finally here, at its highest level since the aftermath of the 2008 crisis:

We don’t know if it’s going to last but wages are finally rising, there is a shortage of seemingly everything right now, consumer balance sheets are shored up and ready to spend and commodities are finally rising.

Yet the bond market doesn’t seem to care. The 10 year treasury yield is back down to 1.5% today.

There are reasons for this.

Baby boomers control most of the wealth in this country and they are all retiring. So the demand remains strong for bonds.

That demand is coming from foreign investors as well, who have even lower interest rates than we do. This is from Axios today:

“We’re seeing an insatiable demand for investment grade credit from Japan,” Matt Brill, head of investment grade for North America at Invesco, tells Axios.

Demand is particularly strong from Japan because the country has adopted a negative short-term interest rate policy, with long-term rates targeted at around zero.

It’s also possible the bond market is behind the eight ball. Rates could be forced to play catch up if higher inflation is here to stay. Or it’s possible the bond market is sniffing out the transitory nature of inflation.

We’ll see. The bond market isn’t all-knowing and all-seeing.

Interest rates are driven by so many different factors — inflation, economic growth, demand for credit, the Fed, government debt levels, etc. — that it’s impossible to nail down the specific reason for their movements.

I also think it’s possible our country simply can’t handle higher interest rates, not now and not in the future.

Barron’s shared a stat this weekend from Peak Capital Management about how debt levels could impact the government’s budget if rates were to rise:

A 3% jump in yields would send the debt service from $303 billion to $975 billion. We would spend more on debt service than defense, and would approach the cost of funding Social Security. The Federal Reserve knows how tenuous the situation can become if yields were to surge higher.

Consequently, they are prepared to provide as much liquidity as possible through direct purchases of Treasuries to keep yields in check.

The Fed and the Treasury are now more intertwined than they’ve ever been (it helps that the current Secretary of the Treasury, Janet Yellen, was the Fed Chair before Jerome Powell took over).

I don’t see how the Fed or Treasury could allow interest rates to get back to 4.5% again at the current levels of debt and spending. I guess it’s possible the government would simply spend even more money but that would be a tough sell if inflation does remain elevated for some time.

Inflation may be even harder to predict than the path of interest rates so we’re in a wait-and-see economic environment but I wouldn’t be shocked if interest rates stayed relatively low for many years.

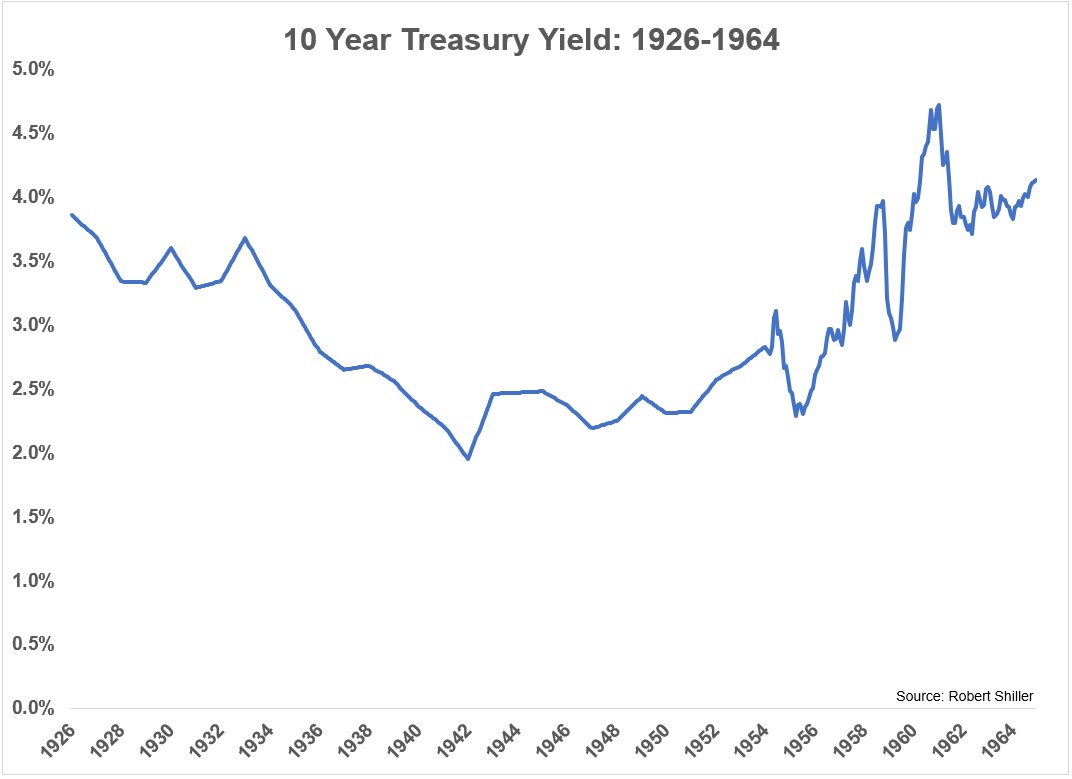

This scenario has precedent. From 1926 through 1964, the 10 year treasury yield was more or less stuck between 2% and 4%:

There were reasons for this. The Great Depression was massively deflationary. Then when the U.S. entered WWII the government put a cap on yields so it could borrow to fund the war efforts. It wasn’t until the latter half of the 1960s that yields finally broke out of this channel for good.

The current channel could be more like 1% to 3% for some time.

Now, you could make the case that higher inflation is a good thing because it actually reduces the debt load in real terms. And if the Fed keeps short-term rates on the floor it’s possible government spending could still be funded with low borrowing costs.

But higher inflation and low interest rates can’t coexist forever. Eventually, something has to give.

The bond market doesn’t seem to care about higher inflation just yet. Maybe it will in the future or maybe we’re just going to get an inflationary head fake from the weirdness of the pandemic economy.

Or maybe bond traders know it’s going to be impossible for the government to allow rates to rise substantially in the year ahead.

Barring a situation in which inflation gets out of control, I don’t see how they can allow rates to go much higher than 3% or so in the coming years.

Further Reading:

What If We Get Inflation But Interest Rates Don’t Rise?