The highest debt-to-GDP on record in the United States came following the massive wartime spending for World War II where it clocked in at roughly 113%.

By my calculations, we just blew past that record and currently stand at a debt-to-GDP ratio of more than 120%.1

People have been worried about government spending for a long time but this year it’s kicked into overdrive.2

The biggest risk of overspending comes in the form of inflation because we can’t run out of money since we print it ourselves.

Some people downplay the threat of inflation following this crisis because it didn’t happen following the Great Financial Crisis but I believe it’s a much bigger risk this time around. The fiscal response wasn’t nearly as strong during or after the 2008 debacle as it has been this time around.

Inflation would be a signal that we beat this downturn but it remains a risk nonetheless.

And if we get inflation, borrowing costs would have to go up, right?

Interest rates and inflation do have a strong relationship over time but it’s not a foregone conclusion that higher prices would lead to higher borrowing rates.

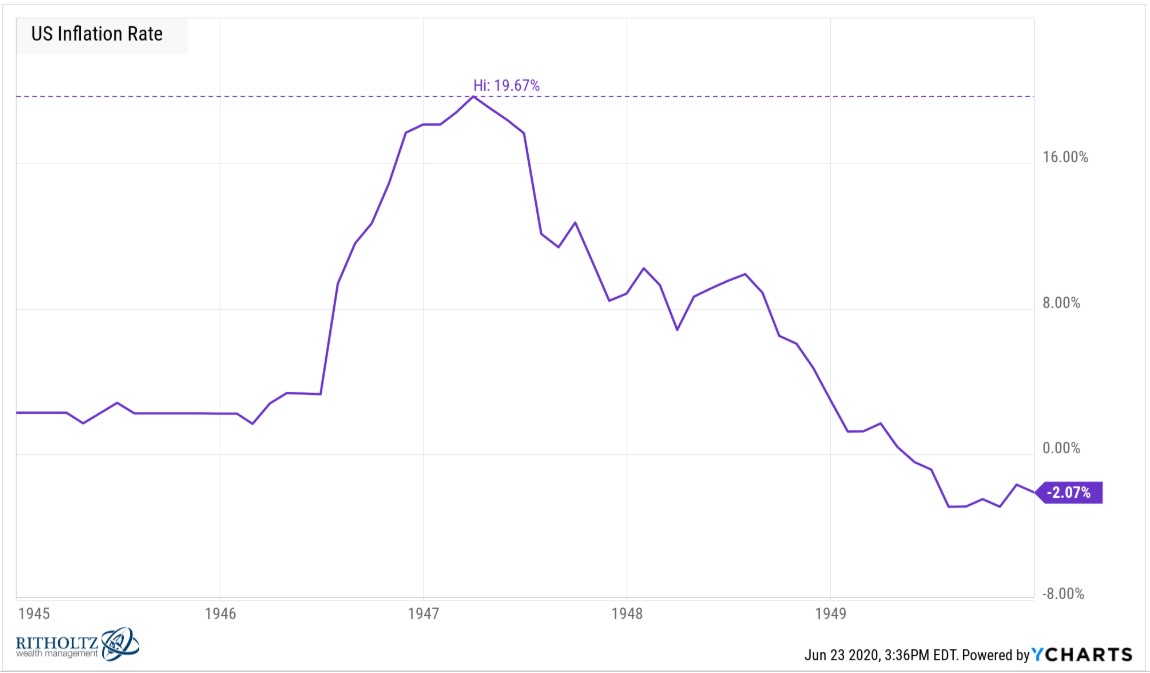

I keep coming back to the WWII scenario because that’s really the only time we’ve experienced debt levels on par with this crisis. All of that wartime spending did lead to a surge in prices as inflation hit nearly 20% in the years following the war:

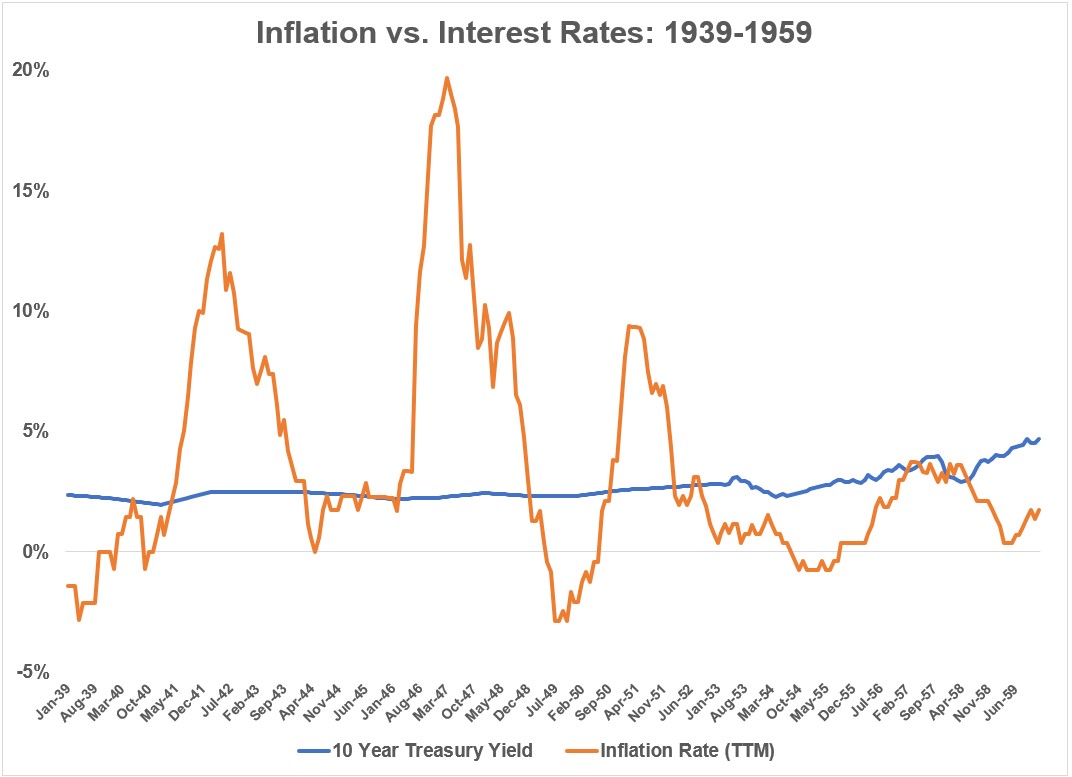

But borrowing rates didn’t budge. In fact, there were three separate inflationary spikes in and around the war years and none of them led to an increase in rates. Here is the trailing 12 month inflation rate along with the 10 year treasury yield from 1939-1959:

Rates were unfazed by that huge post-WWII price spike because the government essentially put a cap on them. Rates didn’t start rising until the late-1950s, long after this spending had worked its way through the system. That inflation was also accompanied by robust economic growth and higher wages for the lower and middle class.

This debt binge couldn’t have played out more perfectly. We spent the necessary funds needed to help with the war effort, prices rose for a short time but borrowing costs stayed muted while people made more money and the economy grew.

Is it asking too much for that to play out this time around? Probably. It’s hard to make historical comparisons when your sample size is one. Plus this is a pandemic, not a war so the economic situation is much different.

But it is possible for interest rates to remain low with a concurrent rise in prices.

My guess is that’s exactly what the Fed will try to do. The Wall Street Journal had an article recently that talked about how the Fed is following Australia’s lead in looking to put a cap on yields to keep borrowing costs low:

The Fed is eyeing Australia’s experience with so-called yield caps, in which a central bank buys enough government securities to prevent their yields from rising above a certain level or to pin yields at specific levels. This helps to hold down private-sector interest rates, which are influenced by government debt yields.

Can the Fed really buy enough bonds to keep yields low in the face of a future that could see higher inflation? I wouldn’t bet against them but even if they can’t my guess is they would simply keep short-term rates low and borrow there.

According to State Street, close to 90% of all new debt issuance has come in the form of short-term t-bills, which effectively allows the Fed to control our borrowing costs and keep them on the floor.3

No one knows for sure whether we will get inflation or not but the risks do seem higher now than they were coming out of the 2008 crisis because of the increased fiscal spending measures.

Even if we do get a spike in prices it’s not a foregone conclusion interest rates will rise along with them.

This may be wishful thinking on my part but please allow me to have a glass-is-half-full moment in what is an otherwise awful year.

Further Reading:

How Would Investors React if We Finally Get Some Inflation?

1Based on our current debt levels of more than $26 trillion and the Q1 GDP figures. It’s also worth pointing out Japan’s debt-to-GDP is in the 200%-300% range.

2And for good reason. We needed it.

3Although they have been extending their duration into 20 year bonds recently as long-term rates have fallen.