When the pandemic began and the gyms shutdown I scrambled to outfit my home gym like so many others.

It’s pretty tough to go running outside in the Michigan winters and I have 3 young kids at home so I liked the idea of a Peloton for cardio purposes. I never would have considered buying one before the pandemic, but Covid forced my hand.1

Somehow we lucked out and got ours shipped in 2 weeks or so. Others haven’t been so lucky. Demand has been so strong average wait times are now 8-10 weeks, sometimes longer.

To fix this bottleneck, Peloton is spending $100 million to invest in their supply chain to speed up delivery times.

It’s interesting to think about this from a purely economic perspective. Peloton could simply raise their prices. Yes, their stationary bikes are already fairly pricey, but I’m guessing many people would pay extra if they knew it would get there sooner.

Instead, we’ve had inflation in wait times and Peloton will pick up the tab by investing in their infrastructure to speed things up.

The severe, yet brief, recession we experienced because of the pandemic is causing shortages like this in all sorts of places. And the problem is not necessarily just demand but a lack of supply.

Supply chains for many products more or less stopped in March and April of 2020 from the shutdowns. And companies pulled back their production because demand typically wanes coming out of a recession. But demand came back much faster than anyone anticipated because people were bored and fiscal stimulus righted the economy in a hurry.

So now there’s a supply problem and companies are scrambling to meet demand.

We ordered a new rack for our dishwasher in November. It just showed up last week. I’ve heard similar stories from people buying appliances throughout the pandemic.

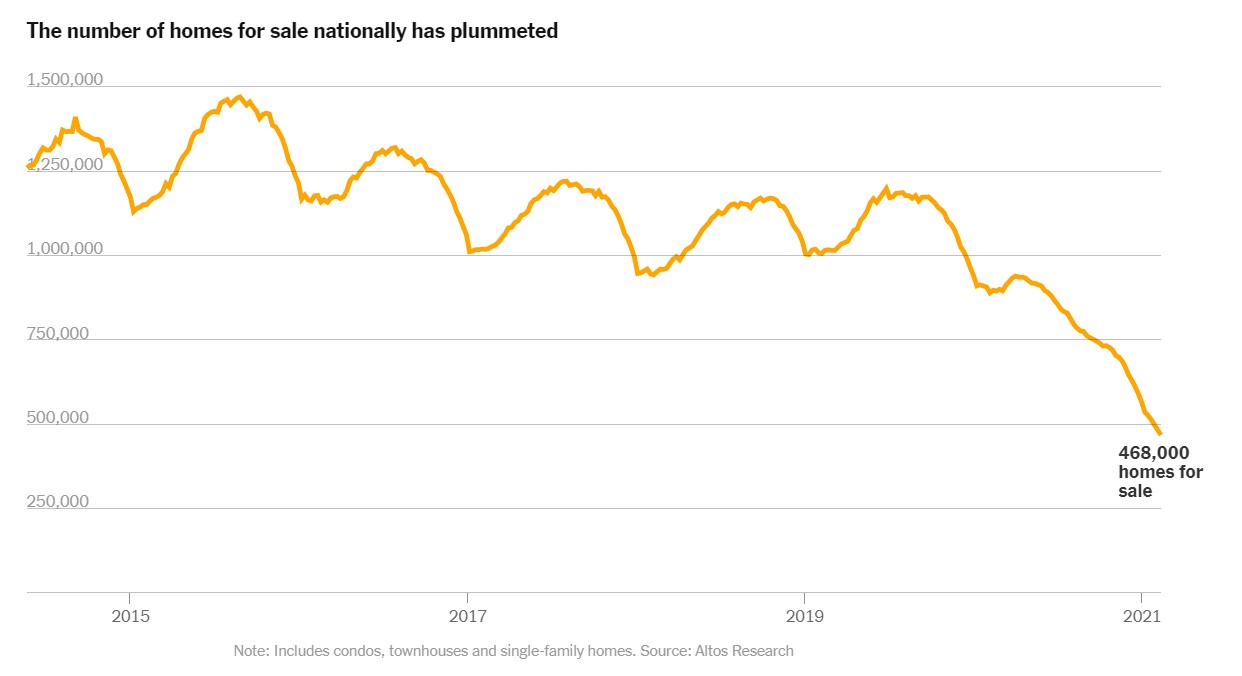

The housing market remains scalding hot, not only because millennials are coming out in force to buy homes, but because supply is constrained.

The New York Times speculates the pandemic had a lot to do with this lack of supply:

There are lots of steps along the “property ladder,” as Professor Keys put it, that are hard to imagine people taking mid-pandemic: Who would move into an assisted living facility or nursing home right now (freeing up a longtime family home)? Who would commit to a “forever home” (freeing up their starter house) when it’s unclear what remote work will look like in six months?

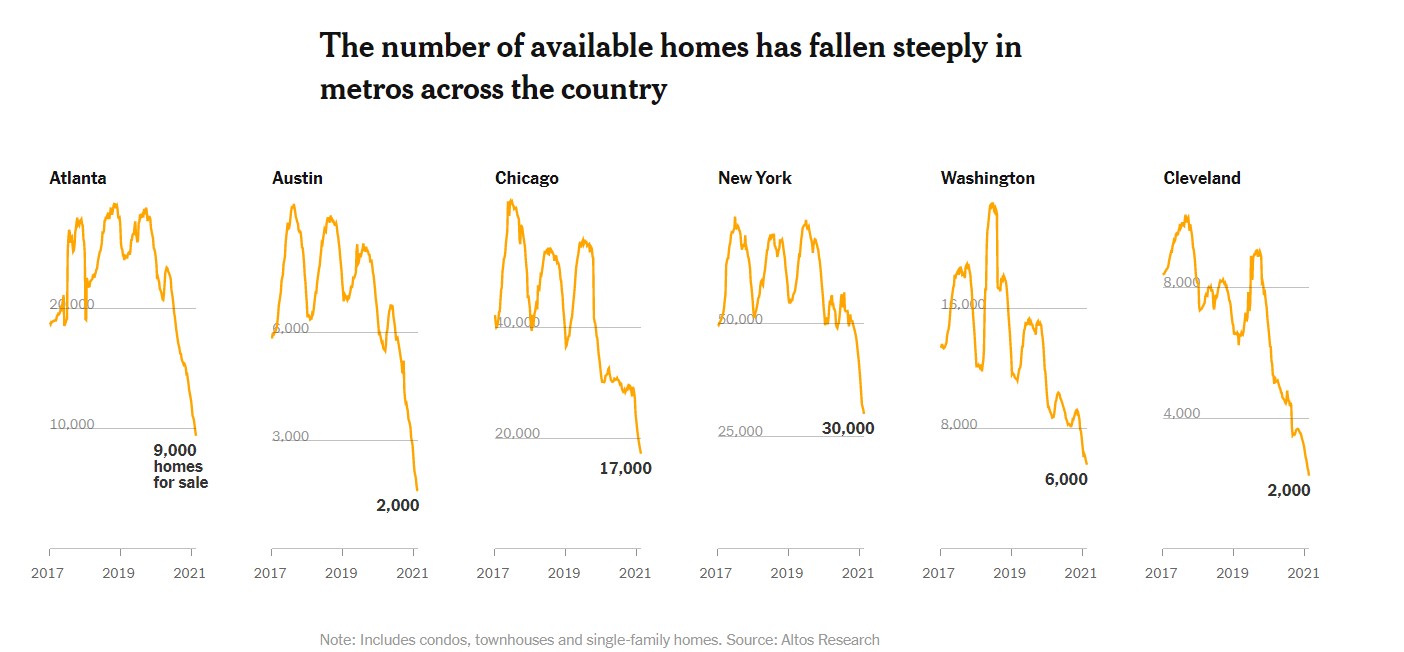

You can see this play out in big cities across the country:

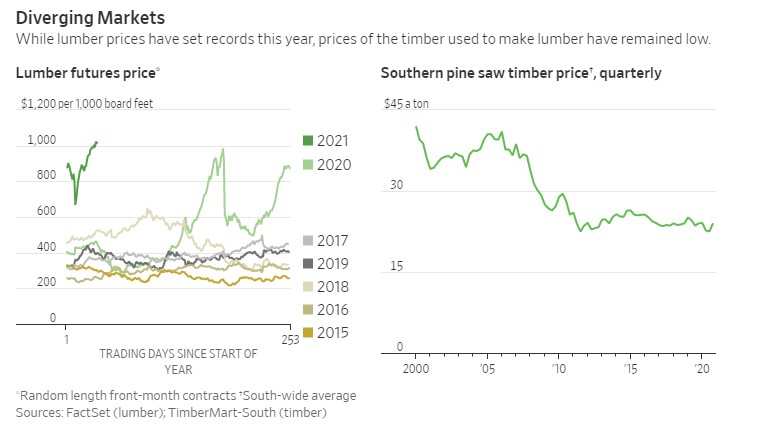

The housing shortage is also showing up in lumber prices, which have spiked to their highest levels ever:

According to the Wall Street Journal, it could take years until supply and demand are back in equilibrium:

The surplus of standing pine is such that growers, foresters and mill executives expect that even with mills sawing at capacity and new facilities coming online, it could be another decade, maybe two, before enough trees are felled to balance supply with demand.

Then there is a semiconductor shortage which is slowing the production of automobiles (also via the WSJ):

Executives at auto makers like Volkswagen AG and General Motors Co. were upbeat about the industry’s recovery in early fall. Demand was rebounding from pandemic lows, and their factories were humming again.

Then came the warnings. Like the one in a Nov. 12 Skype call between VW’s logistics head and officials at car-parts supplier Continental AG . The supplier said it wouldn’t deliver a range of core components VW needed because of a global semiconductor shortage, said people familiar with the call.

Other car makers were getting similar alerts from suppliers.

In December, the parts flow from Continental, Robert Bosch GmbH and other suppliers had so dried up that VW announced it would stop production of bestselling brands such as Audi and its namesake VW brand at plants in Europe, China and North America. Audi, citing a chip shortage, furloughed 10,000 factory workers for the first time since the spring lockdowns. Ford Motor Co. , Honda Motor Co. and others soon reduced output of vehicles from big pickups to compact sedans.

Auto executives think these supply chain issues could last well into next year.

You could also make the argument we’ve had a shortage of financial assets for years now. Bloomberg reported last week two year treasury bonds were sold at a premium for the first time in history:

“When the Fed’s committed to keeping rates at or near zero, twos are probably cheap at 10 basis points,” said Glen Capelo, managing director at Mischler Financial, who began trading Treasuries in 1986. “It’s a little crazy that you have to buy them at that yield, but that’s your choice.”

Ten basis points in yield and they sold at a premium because demand was so high. What a world.

And look at the insane rise in SPAC deals over the past year or so:

Over 130 and counting in 2021 alone. There was obviously a shortage of public companies that Wall Street is desperately trying to fill.

It’s possible everything is backwards now because the Corona recession was so unique.

But it’s also possible the pandemic may have broken many historical relationships in terms of the business and stock market cycles.

It will be interesting to see how companies and markets react in the next downturn with this knowledge.

Further Reading:

The Most Counterintuitive Recession Ever

1My Peloton review: I like it and the more I use it the more I like it. This company could be massive someday if they continue to innovate in the space (but fitness is a fickle industry so who knows). The New York Times even interviewed me about our Peloton purchase in the spring.