In 1996, comic book maker Marvel filed for bankruptcy after racking up $700 million of debt and owing payments on $1 billion of bonds to investors.

During the bankruptcy proceeding, a number of studios performed their due diligence and came close to buying the company but none came closer than Sony.

Instead of buying the company outright, Sony wanted to secure the rights for the Spider-Man franchise to begin making movies about Peter Parker. Fresh out of bankruptcy and in dire need of cash, Marvel responded with a counteroffer. They offered Sony the movie rights for all of their biggest characters — Iron Man, The Black Panther, Thor, Ant-Man, etc. — for $25 million.

A young Sony exec named Yair Mandau was tasked with securing the Spider-Man rights. As told in Ben Fritz’s excellent book The Big Picture: The Fight For the Future of Movies, this is how Mandau’s bosses responded to the offer:

It didn’t take long for them to quickly and decisively respond: no way. “Nobody gives a shit about any of the other Marvel characters, we don’t want to do that deal,” they told Landau, as if he were Jack coming home with a handful of magic beans. Their instructions to Landau, they thought, were quite simple: “Go back and do a deal for only Spider-Man.”

Shockingly, Sony ended up paying $20 million for Spider-Man alone. They could have had the rest of the Avengers for just $5 million.

That deal could have made Sony billions of dollars and made the studio the next Disney, the company that eventually purchased Marvel. Instead Marvel created a cinematic universe that would make billions.

It’s obvious with the benefit of hindsight that Sony screwed up but you can’t really blame them. Every other studio passed on those Marvel assets as well. The Avengers were sitting there for the taking but no one thought it would become the biggest movie property in history.

At the time, movie studios were printing money at the box office and DVD sales on all kinds of different movies. No one saw how this dynamic would change with the onset of streaming videos and higher quality shows on TV which cannibalized the movie industry.

It wasn’t obvious superhero movies and sequels would become the only profitable ventures. There had been a number of failures in the space so it wasn’t a foregone conclusion Iron Man and friends would do as well as they did.

William Goldman has one of the more impressive IMdB pages of any screenwriter in Hollywood. His credits include The Princess Bride, Butch Cassidy & The Sundance Kid, Misery and All the President’s Men.

In his book Adventures in the Screen Trade, Goldman discussed how difficult it is to know what’s going to work in Hollywood: “Nobody knows anything…Not one person in the entire motion picture field knows for a certainty what’s going to work. Every time out it’s a guess and, if you’re lucky, an educated one.”

Just look at Quibi, the streaming service that launched with nearly $2 billion of capital and stars galore for their smartphone-only shows. They came online during a pandemic when no one had anything but time on their hands and couldn’t make it 6 months.

Predicting the future is hard because the past makes it seem easy.

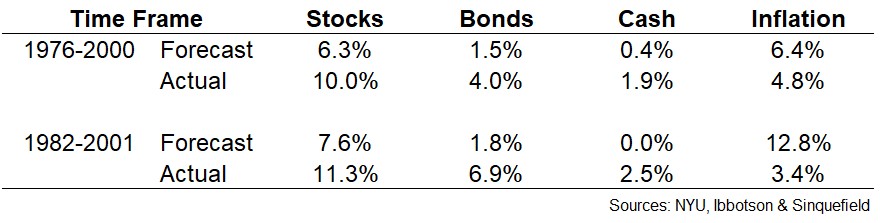

In 1975, two market researchers put together a forecast of financial returns called Stocks, Bonds, Bills and Inflation for the coming 1976-2000 period using strong theoretical support and historical market data. They performed a follow-up simulation for the 1982-2001 period as well.1

The researchers provided forecasts the after-inflation returns for stocks, bonds and cash as well as the inflation rate itself. Here are those forecasts along with the actual results:

The stock, bond and cash expectations were far too low while the inflation forecasts were far too high.

While it would be easy to chalk this up to the folly of forecasting you also have to remember the market environment when these forecasts were made.

Markets stagnated for much of the 1970s as inflation was running rampant. By 1982, investors had just witnessed three years in a row of double-digit inflation and rising interest rates.

It looks obvious now that bonds would be in a prolonged bull market but the reason investors pushed interest rates so high was the understanding that they would still only get 2-3% on a real basis since inflation was running so high.

No one was predicting a 40 year period of disinflation and rapidly rising stock market valuations in the late-1970s or early-1980s because there were few signs this could possibly be the case.

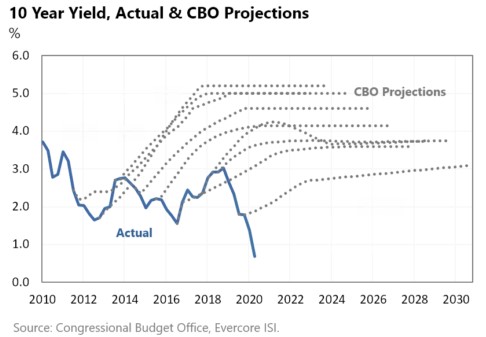

And even as rates have been a freefall for decades, every single year people have been predicting them to rise because it seemed like there was no way they could possibly go lower:

Right now it would be easy to assume rates will stay low forever, tech stocks will always dominate, U.S. stocks will continue to beat the pants off foreign stocks and inflation will stay subdued for decades.

It’s possible these things will carry on for some time but the idea that the current state of affairs will remain in place would be a mistake. Nothing lasts forever in the markets.

Peter Bernstein once wrote:

All of history and all of life is stuffed full of the unexpected and the unthinkable. Survival as an investor over that famous long course depends from the very first on recognition that we do not know what is going to happen. We can speculate or calculate or estimate, but we can never be certain.

Bernstein says diversification provides the only dependable way to survive the unexpected and unthinkable.

It’s also worth reminding yourself on a regular basis that nobody knows anything when it comes to the future.

Further Reading:

No One Knows What Will Happen

1I found this research in an old Peter Bernstein piece and re-created the results on my own.