Attention investors: We are now raising capital for a new distressed fund to take advantage-

[markets rise 35%]

-never mind

— Ben Carlson (@awealthofcs) April 30, 2020

In my endowment fund days we invested with a distressed fund manager who set up two different funds structures.

Fund A was a standard distressed fund that would invest in various credit structures in higher-yielding areas of the debt markets. Fund B was set up as a back-up to Fund A in the event that things became so dislocated that the fund manager could call in whatever money you pledged so they wouldn’t have to go through the fundraising process before swooping in to scoop up any deals that would potentially come out of nowhere.

Both funds were created in the aftermath of the financial crisis so Fund B sat dormant for many years and was never called in since there was never enough distress in the credit markets. Fund A had a hard enough time finding distressed assets to purchase.

So you better believe many investors who hang their hat on buying assets at distressed prices had to be licking their chops when markets when haywire in March. I’m sure there were a number of fund managers who were getting ready to back up the truck in hopes of seeing dislocations of 40%, 50%, maybe even 60%-70% in the markets.

That may have been the case for some of the worst-hit segments of the stock market but the markets moved so quickly in both directions there really wasn’t time to wait for the fat pitch. If you didn’t act swiftly you missed the worst of the bear market.

For weeks investors were speculating when Warren Buffett would step up to the plate to unload his billions in cash waiting patiently on the sidelines. That moment never came, most likely because markets fell, then rallied so quickly.

Buffett talked about why this was the case in his four-and-a-half-hour annual meeting that streamed live on the Internet last weekend:

There was a period right before the Fed acted. We were starting to get calls. They weren’t attractive calls, but we were getting calls and the companies we were getting calls from after the Fed acted, a number of them were able to get money in the public market. Frankly terms we wouldn’t have given it to them.

Now it makes more sense why Buffett wasn’t buying.

The worst of the downturn was over so quickly he didn’t have time to negotiate more favorable terms with companies he was interested in. The Fed stepped in before prices could reach the distressed levels he was used to seeing that would force company management to offer Buffett investment terms others could only dream of.

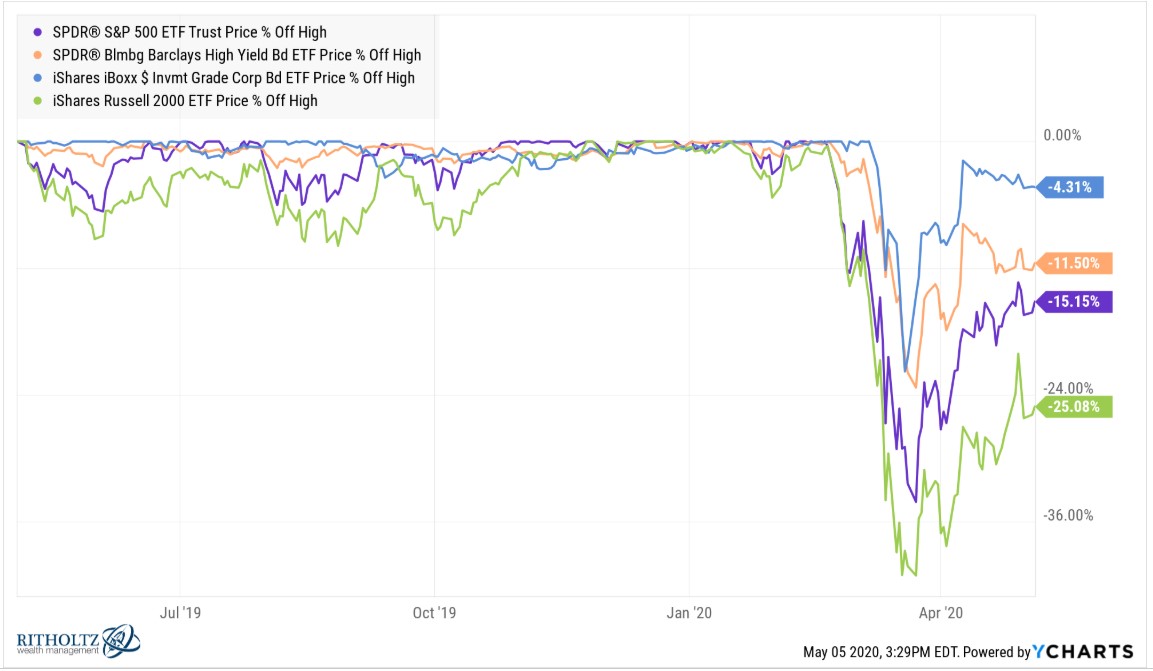

The broader markets are still down but you can see how vicious both the sell-off and rally was in stocks and corporate credit:

It was a blink and you missed it scenario for many investors.

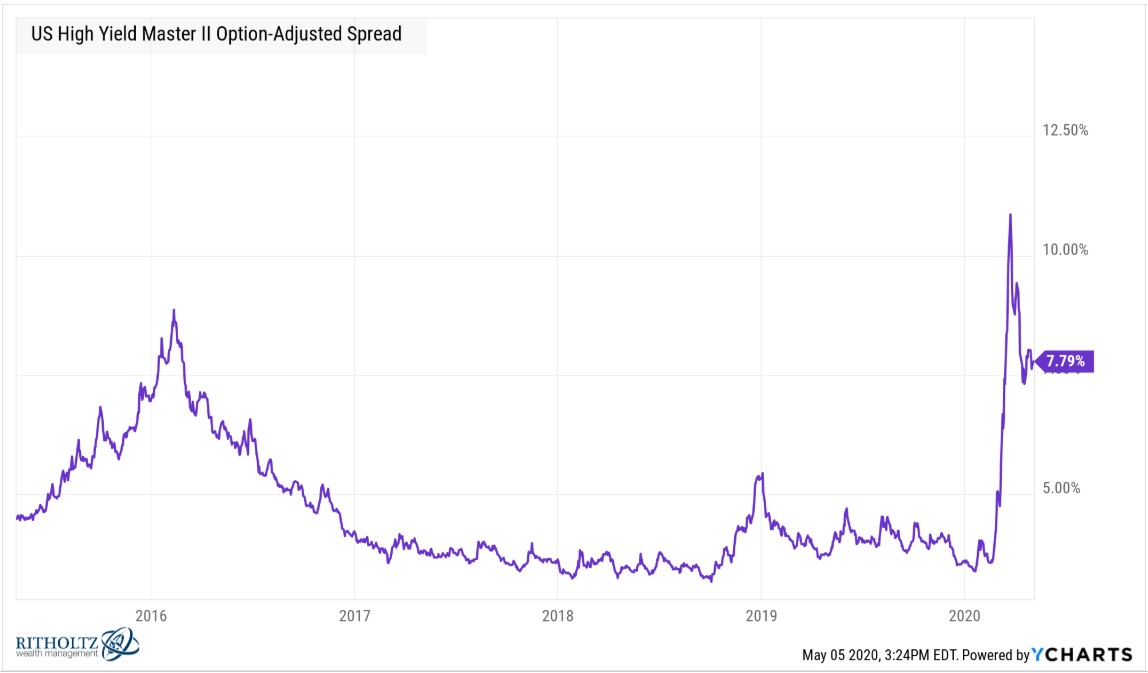

High yield spreads blew out very quickly but have contracted to levels last seen in 2016, which was a forgettable correction that no one really remembers anymore:

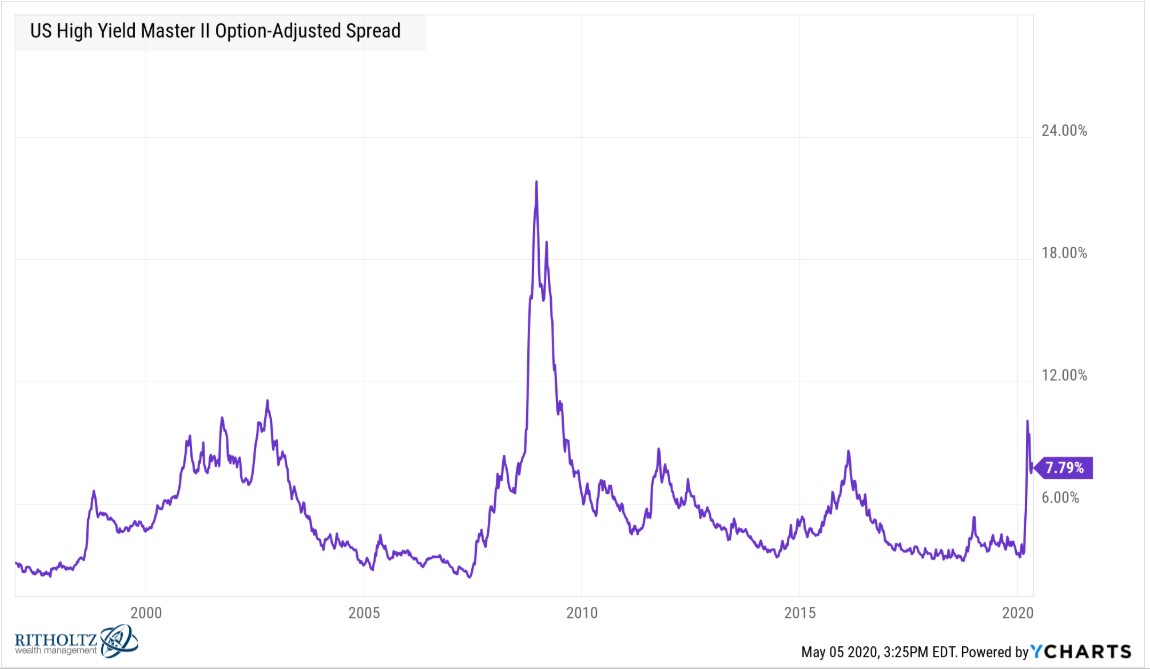

Spreads between high and low quality debt never got anywhere near as wide as they were during the Great Financial Crisis:

I’m sure a number of investors were hoping for a similar blowout to that unbelievable 20%+ spread of 2008.

Buffett sang the praises of Jerome Powell and the Fed for acting so swiftly but this helps explain why so many professional investors are so critical of the Fed. The Fed is making it much harder for them to see attractive marks to invest in during this crisis.

The Fed’s balance sheet has ballooned to well over $6 trillion which is obviously [checks notes] a boatload of money.

But you could also make the case that much of what the Fed has done in terms of moving markets is psychological.

Bond fund manager extraordinaire Jeffrey Gundlach tweeted the following this past week:

I am told the Fed has not actually bought any Corporate Bonds via the shell company set up to circumvent the restrictions of the Federal Reserve Act of 1913. Must be the most effective jawboning success in Fed history if that is true.

— Jeffrey Gundlach (@TruthGundlach) May 1, 2020

A number of investors were left scratching their heads when the Fed announced they would begin buying up corporate bonds and potentially junk bond ETFs. Maybe they still will at some point but if they don’t it’s impressive that all it took was their stamp of approval to move the markets. They didn’t even have to buy the actual bonds, just say it was in their arsenal.

Obviously, things are happening so fast in the markets these days that we could still see distressed prices crop up at some point during this crisis. This thing is a long way from being over.

I do wonder if this situation could change the way investors think about investing during bear markets in the future:

- Will fund managers be quicker to react during a downturn?

- Will investors be more willing to buy the dip?

- Will this lead to fewer opportunities to buy at severely distressed prices?

- Will more investors exhaust their dry powder too early during a prolonged bear market?

- What if the window for swinging at fat pitches is much smaller than it’s ever been?

- Will the Fed be able to retract their tentacles from the markets or will they play an ever-larger role going forward?

- What if the Fed’s psychological power over the market eventually wanes?

- How will this impact investor risk appetites going forward?

No one knows the answers to these questions because they are psychological in nature and human beings are tough to predict in terms of their over- or under-reactions based on their experiences.

I’m fascinated by the potential behavioral changes this crisis could bring in the months and years ahead. No one knows for sure how long-lasting many of the changes will be from this virus.

Human nature doesn’t change overnight but investors are often driven in many ways by their memories and past experiences with markets.

I wonder if this crash will change the way some investors think about investing in distressed assets in the future.

Further Reading:

My New Theory About Future Stock Market Returns