Netflix claims Martin Scorcese’s movie The Irishman was streamed more than 26 million times in the first week of release on the streaming platform. They estimate that number will jump to 40 million by the end of the first month.1

One of the reasons I was so excited for this movie is because I read the book it was based on just a few short months before it came out. I loved the book which had an even better name than the movie — I Heard You Paint Houses by Charles Brant. Brant interviewed Frank Sheeran (played by De Niro in the movie) on his death bed and got some wild stories from the former hitman.

(If you would like my ridiculously long review of the movie, just listen to the first 10 minutes of our podcast from a few weeks ago.)

The book covers the organized crime angle and the mob’s relationship with teamster extraordinaire Jimmy Hoffa just like the movie but it also provides more perspective on just how powerful those unions were back in the 1950s, 1960s, and 1970s. Sheeran felt Hoffa was as famous as Elvis or The Beatles back then.

Here are some stats and anecdotes from the book about the bargaining power these unions had in those days, which in turn, gave workers bargaining power:

- In the two years following World War II, there were a total of 8,000 union-led strikes in 48 states. That’s more than 160 a year per state.

- Truck drivers were one of Hoffa’s biggest union chess pieces. Because they could strike at any moment and basically shut down the country’s supply chain, Bobby Kennedy called Hoffa’s teamsters, “the most powerful institution in the country aside from the United States government….and as Mr. Hoffa operates it, this is a conspiracy of evil.” Another senator called the unions under Hoffa’s leadership “a superpower in this country.”

- Hoffa created a pension fund where the companies these unions worked for were forced to make regular contributions. The way Hoffa got involved with the mob is he would loan them money from this pension fund (which grew quite large) to finance the more legitimate portion of their criminal enterprises.

- In his book, The Teamsters, Steven Brill says at one point in the mid-1970s, the teamsters’ pension fund had loaned out more than $1 billion for commercial real estate projects such as casinos that were run by the mob. At the time, that was just 20% less than the amount loaned out by Chase Manhattan Bank.

- When Hoffa orchestrated the Master Freight Agreement, which covered truckers nationwide, they were all given the same (increased) hourly wage, the same benefits and the same pension. That was there was just one contract to negotiate for every trucking company in the country. This is how the threat of a strike could turn nationwide in a hurry because they were all on the same terms.

You would be hardpressed to find a period in modern history where workers had more leverage than this.

Of course, it couldn’t last because they also had the mob scaring replacement workers off when they crossed the picket lines during a strike. And the government tends to frown upon loaning money out to mobsters from your tax-free pension plan so they can start casinos to launder all of their dirty money.

But it wasn’t just Hoffa’s teamsters who held all of the bargaining power back then. The auto unions grew to be just as powerful and may have even been better negotiators.

Roger Lowenstein details the history of pension funds through the lens of the big three auto manufacturers in his book While America Aged. By 1960, 40% of American workers were covered by a pension. By the end of the decade, that number was closer to 60% for the private sector.

Either the autoworkers had the greatest negotiators on the planet or the management at General Motors, Ford and Chrysler were asleep at the wheel because the benefits they received were staggering.

Here are some details from the book:

- In the 15 years ending 2006, GM was forced to add $55 billion into its pension plan for workers compared to $13 billion paid out in dividends for the stock. And this doesn’t include the money spent on healthcare benefits for retirees.

- By the 1960s, pension benefits were rising at 3 times the rate of wages in the country. At Ford specifically, wages had risen fivefold since 1950 but pension benefits were up 10 times.

- If you retired from GM in 1950 you were paid an average pension of $45/month. By 1980 that same retiree was collecting $435/month. That growth was triple the level of inflation over that time.

- Because of the onerous benefits being paid out, by 1990, GM’s stock price was exactly the same level it had been 25 years earlier.

- GM invested so much money into its pension plan in the mid-1990s that it could have acquired half of Toyota Motor Corp with that money.

- When these pensions were enacted, GM simply didn’t factor in the fact that people would be living longer in the future. There was one employee who lived to be 111 years old. When he died he had been collecting pension and healthcare benefits for 48 years! When this employee first entered the plan in 1926, there’s no way GM was planning on nearly 5 decades of benefit payments.

As with most things in life, the unions took things way too far, got way too greedy and the script has flipped.

Bargaining power for labor declined substantially from the 1970s onward. Union membership fell. Globalization took over the economy as access to cheap labor made it easier to produce in other countries (and those countries didn’t have legacy pensions to deal with). Workers also began switching jobs more often, making it harder to use pensions as a bargaining chip.

As people began living longer and pensions became woefully underfunded, companies saw the writing on the wall. The advent of the 401k in the 1980s was the final nail in the coffin. Today the number of private-sector workers with a pension plan is closer to 15%.

A couple of months ago I wrote about the idea that World War II was an economic anomaly. A confluence of events more or less created a burgeoning middle class, cheap housing, and rising wages. This period during the 1950s and 1960s also happens to line up with Jimmy Hoffa’s reign as king of labor unions, the mob making sure no one crossed the picket line during a strike and autoworkers retiring at age 55 with healthy pension and healthcare benefits.

Over the past 4-5 decades things have swung in the other direction as capital (read: financial markets or corporations) regained the upper hand over labor (read: workers).

The pension/union system of old was far better for stakeholders because it meant employers were forced to take care of their own. But the unions got greedy, people started living longer, and the workforce changed.

I wonder if the events that caused labor to gain so much power in the 1950s and 1960s was a flash in the pan. I hope I’m wrong but it feels like employers still have the upper hand over employees and it’s hard to envision a scenario where that changes any time soon what with the efficiency gains from technological innovation.

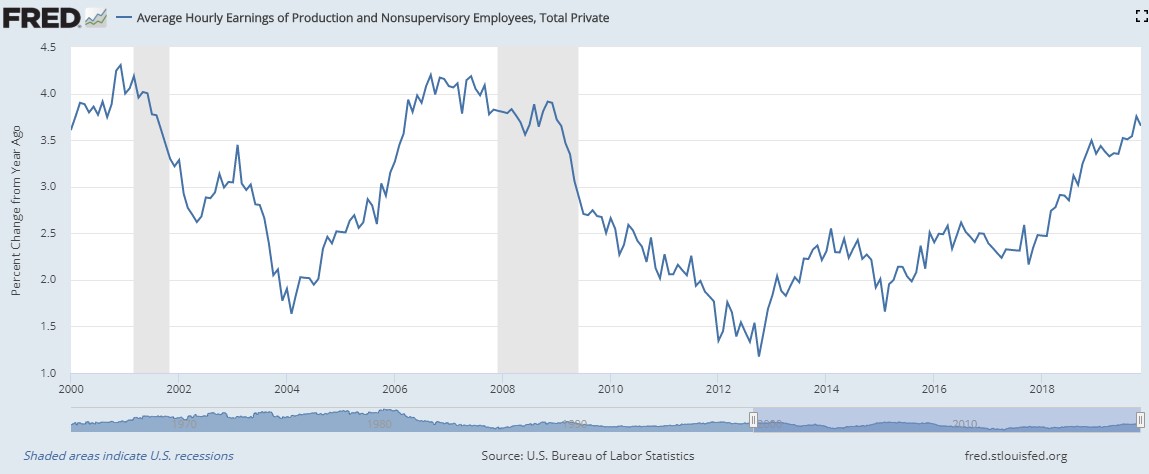

On the positive side of the equation, wage growth is finally accelerating now that the unemployment rate is well below 4%:

A prolonged environment of full employment, if there is such a thing, may be the only set up that can give labor more power for an extended period of time.

Again I hope I’m wrong, but it feels like the heyday of Jimmy Hoffa was the anomaly.

Further Reading:

Wage Growth vs. the Stock Market

1It’s also estimated only 18% of viewers made it to the end. The Irishman is the Thinking, Fast and Slow of movies. Everyone says they read (watched) it but barely anyone actually finished it.