In his excellent market history book, It Was a Very Good Year, Martin Fridson tells the story of the year that was in the market in 1915.

It remains one of the strongest years on record for the stock market, which was up more than 50%, even though World War I was well underway at the time.

Fridson discusses how differently stocks were viewed in the early 20th century than they are now:

Journalists commonly equated the established dividend payout with the return on the stock, giving little thought to possible appreciation. They compared the payout rate directly with bond yields; total return’s day hadn’t yet arrived. The prevailing orthodoxy held that dividend yields had to exceed prevailing interest rates on bonds to compensate for the greater uncertainty of payment. Not until several decades after the Big Board stopped quoting stocks like bonds would this mindset change.

The big changeover came in the 1950s when the dividend yield on the stock market finally dipped under the yield on government bonds. Until the 1950s, when bonds yielded more than stocks it was a clear signal that it was time to get out of the stock market.

That relationship broke down and I think one of the reasons it happened is because investors became more comfortable with the capital appreciation side of the return equation. The stock market was maturing as were investors.

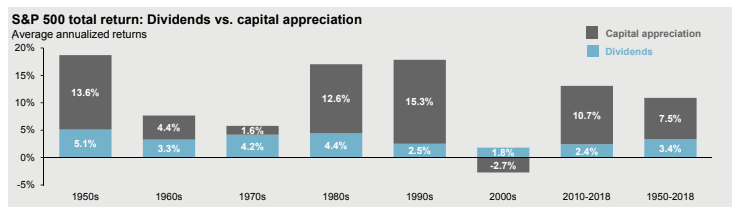

In the latest JP Morgan Guide to the Markets they compared dividend to capital appreciation by decade going back to the 1950s:

You can see dividends were still a healthy 3-5% from the 1950s through the 1980s. Now you can see a slow progression down in the importance of dividend yields since the 1990s.

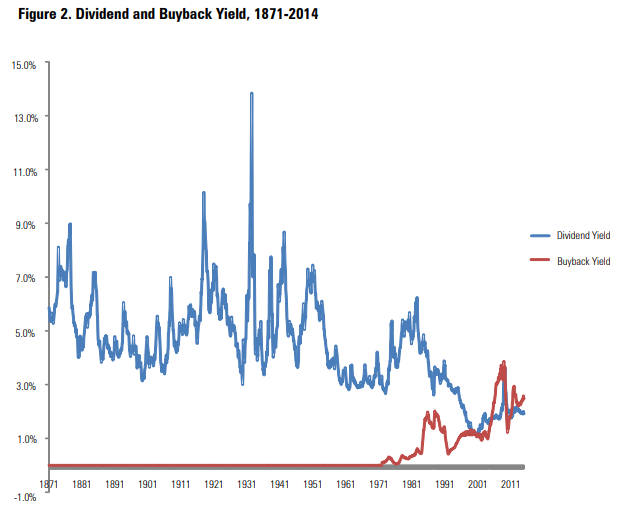

One of the biggest reasons for this shift is the increase is stock buybacks. In the early 1980s, the SEC instituted a new regulation that gave corporations incentives to repurchase their own shares. You can clearly see how this trend has changed stock yields over time:

Dividend yields were already beginning to fall but buybacks have accelerated the process as corporations have used them as another way to return money to shareholders.

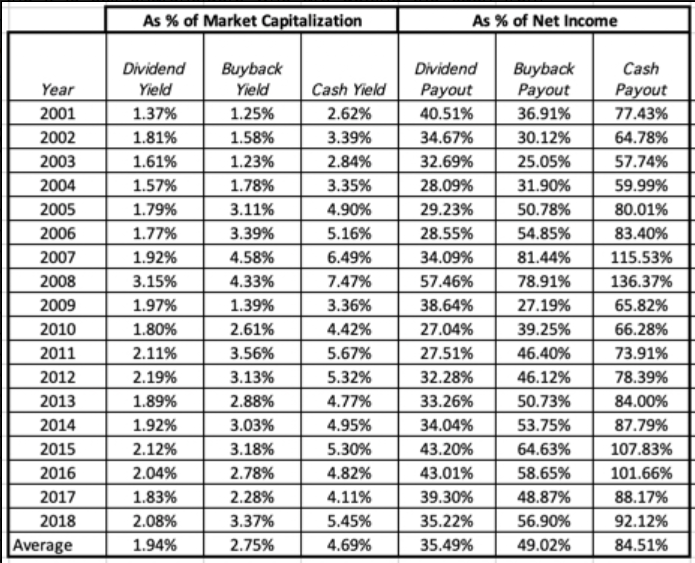

Aswath Damodaran broke these yields down by year on his blog recently:

It didn’t take long for the buyback yield to supplant the dividend yield on the S&P 500. In fact, the buyback yield has now been higher than the dividend yield for the past 9 years in a row.1

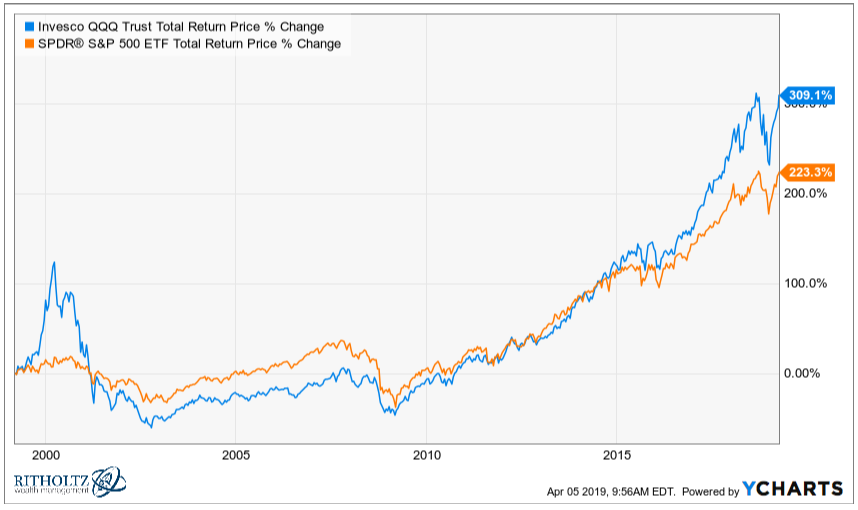

Another way of thinking about the shrinking importance of dividends is by looking at the yields on both the S&P 500 and more tech-heavy Nasdaq over time:

The Nasdaq 100 has barely sniffed 1% in dividends but has still managed to outperform the S&P handily:

You could claim recency bias here but the Nasdaq has actually beaten the S&P over the long haul as well.

From its inception in 1973, the Nasdaq Composite Index has returned roughly 11% per year. In that same time, the S&P 500 has returned around 10.4% annually.

Beyond buybacks, one of the biggest reasons for the lower dividend yield on the S&P 500 is the change in sector composition over time.

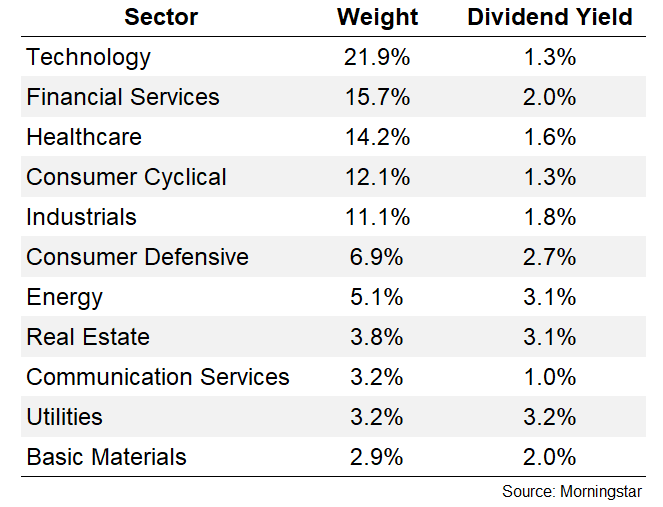

Here are the current sector weights of the S&P 500 along with the corresponding dividend yields:

The average dividend yield for the top 5 sectors by weighting (which make up over 75% of the index) is 1.6%. The average dividend yield for the bottom 6 sectors (which make up less than 25% of the index) is 2.5%.

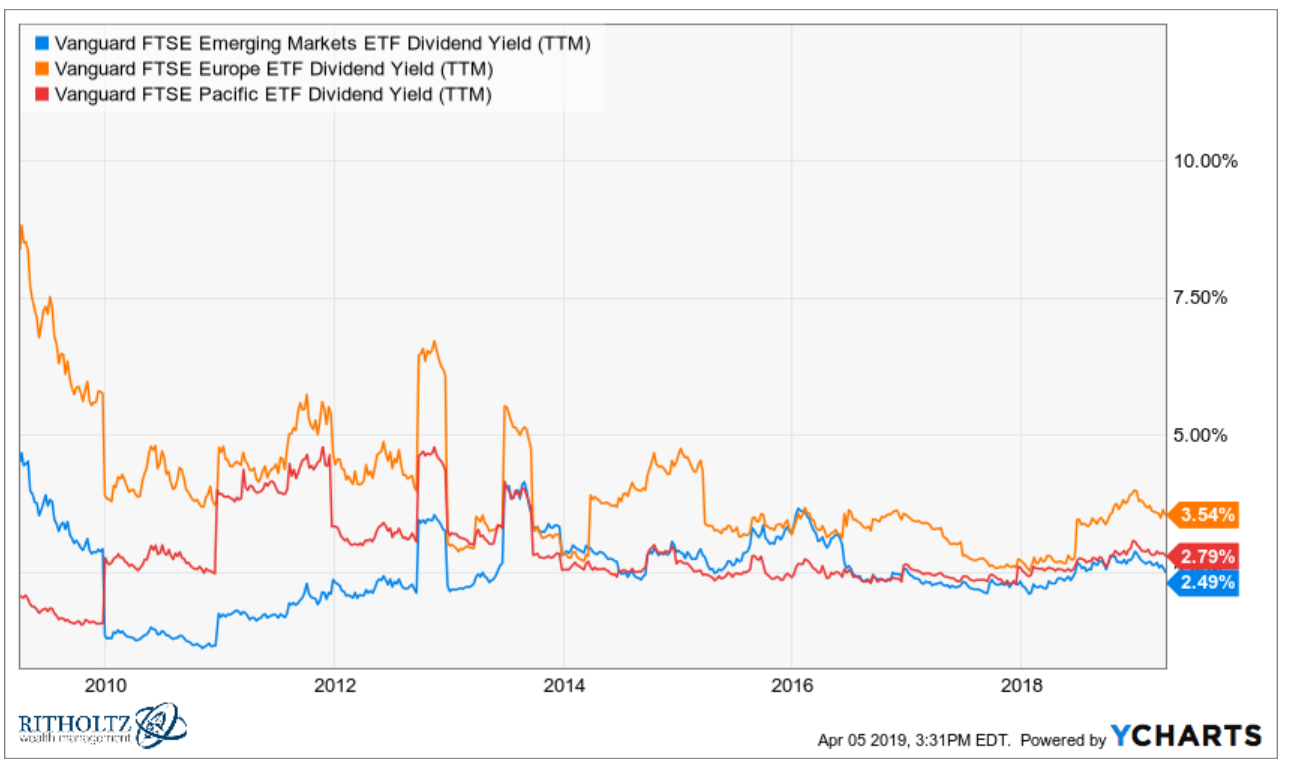

This is mostly a U.S. phenomenon. International stocks still have higher dividend rates:

This is partly buybacks, partly sectors, and partly the stronger performance in the U.S.

I’m not saying dividend strategies don’t matter anymore; just that dividends don’t play as big of a role in market cap weighted U.S. indexes as much as they used to.

It’s certainly possible dividend-based strategies or even those sectors with higher dividends could do better from here, especially given the strong run in tech stocks over the past decade or so.

But it is fascinating to witness the structural changes in the way dividends are viewed over time.

In the past, dividends were the only reason investors placed their money in equities. Now, dividends play a much smaller role, for better or worse, in the overall stock market.

Further Reading:

The Half-Life of Investment Strategies

1Cue the conspiracy crowd who will complain the market has been manipulated by buybacks.