Vanguard launched its first index fund on the last day of 1975. It wasn’t exactly a hot product straight out of the gate considering they hoped to raise $150 million but instead brought in just $11 million.

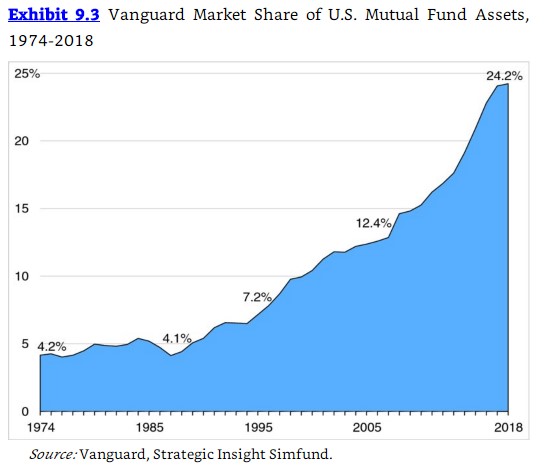

Vanguard’s share of industry assets actually fell throughout much of the 1980s, going from 5.8% in 1981 to 4.1% by 1987. By 1991 market share had grown to 6.2% of the industry but much of that growth actually came from the introduction of money market funds and the growth in the mutual fund complex itself.

By 1992, Vanguard managed $92 billion. That grew to $555 billion by 2002, $1.1 trillion by 2006 and more than $5 trillion by the end of 2018. Vanguard’s market share of industry assets doubled between 2006 and 2018 from roughly 12% to 24%:

Index funds at the firm also took some time to heat up. In fact, 98% of Vanguard’s assets were in actively managed funds in 1981. Index funds at Vanguard grew from $50 billion in 1996 to $3.3 trillion by the end of 2018, now making up around three-quarters of firm assets.

John Bogle admitted in his book, Stay the Course, that someone else surely would have come along eventually to create an index fund for the masses. But it would have taken a while:

Without Vanguard, the creation of the index fund would have occurred anyway, I’m sure. But it likely would have been delayed by another decade or two. Our mutual structure, however, has yet to be copied.

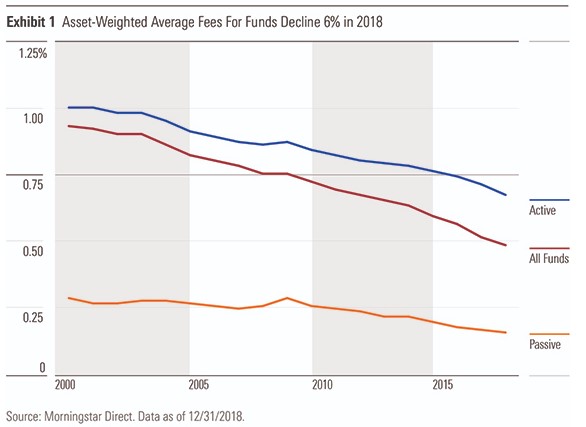

You could make the argument that Vanguard has single-handedly lowered fees across the board in the fund industry over the past couple of decades (chart via Morningstar’s annual fee study):

Considering the firm has been around for more than four decades, this change was a long time coming.

Interestingly enough, the very same year Vanguard launched their first index fund brought another sea change for investors when it came to the cost of investing. In what is now called May Day, on May 1, 1975 regulators abolished fixed-rate commissions on stock trades. This essentially allowed for competition for the first time in trading fees (investors were paying around 2% or so on every trade).

This has also taken a while to work its way through the system, but trading costs have come down exponentially ever since.

Until we get paid to make stock trades in the future (I’m holding out hope for credit card-like rewards points), this trend more or less came to its conclusion this week.

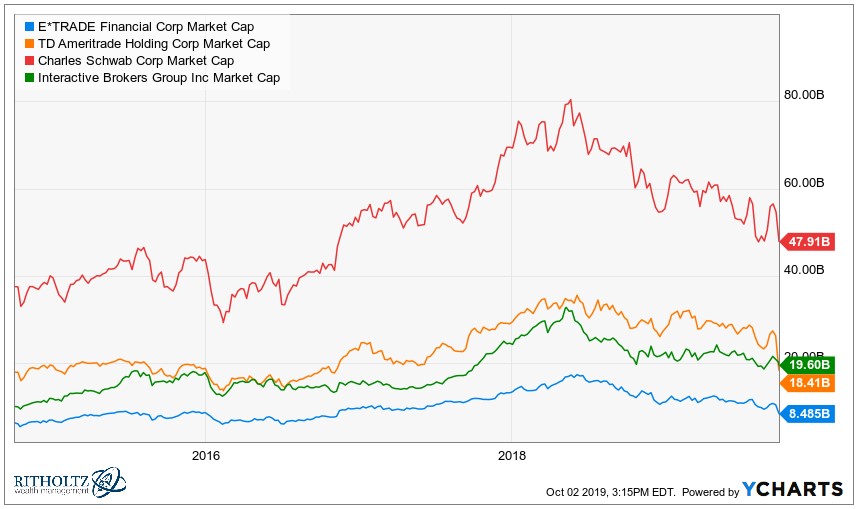

After Interactive Brokers announced they were offering free stock trades on their platform last week, Charles Schwab followed suit earlier this week, TD Ameritrade quickly made a similar move shortly after the Schwab announcement, and then E-Trade fell in line the next day.

This trend was likely pushed into overdrive by a company founded in 2013. Commission-free trading app Robinhood likely forced the issue for these other firms to lower fees to the floor much like Vanguard’s push into index funds forced the hand of other fund firms to lower their fees.

Fees for stock trading have been heading to zero for some time now but Robinhood likely sped up that process. I don’t know what it means for Robinhood as a company going forward but I do believe they gave the entire segment of the market a kick in the pants to lower fees.

Some other random thoughts on the great fee wars of the 2010s1:

The benefit of all the money sloshing around in private markets. If the private markets were in a bubble they are now slowly starting to deflate, especially in high profile tech names.2 If that’s the case, so be it. The legitimate businesses will stand the test of time while the posers will eventually fade from public consciousness.

All that money sloshing around in private markets has been wonderful for consumers. Uber and Lyft reinvented the transportation industry. Airbnb changed the home rental industry. WeWork has made it easier for entrepreneurs and small businesses to find nice co-working spaces. And Robinhood has made it cheaper and easier to invest in stocks.

The most recent funding round places the valuation of the company at nearly $8 billion. That’s not bad considering it’s equivalent to the market cap of E-Trade and roughly half the market cap of TD Ameritrade or Interactive Brokers:

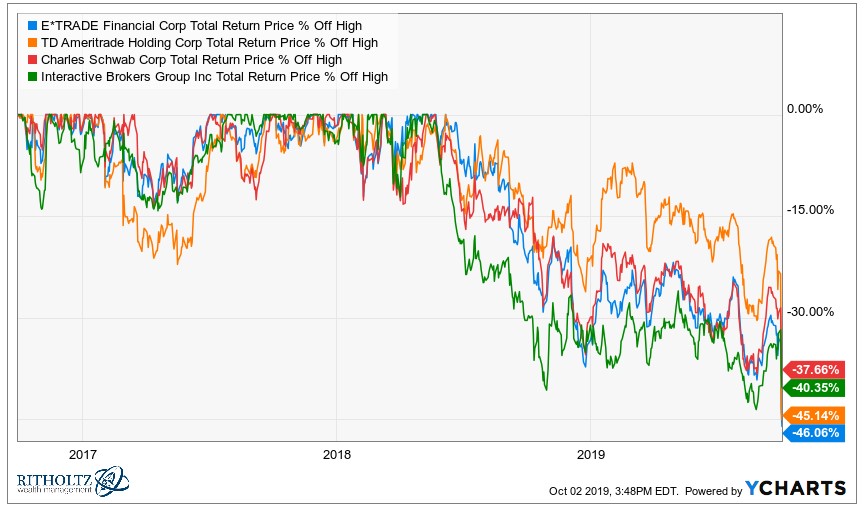

I’m guessing you can throw that $8 billion valuation out the window as you can see from the returns in these very same stocks this week:

So even if Robinhood doesn’t become the financial hub of the future for the avocado toast generation, they’ve provided a great service for financial consumers by forcing the issue for the more established players.

These firms will figure out ways to make money in other ways. Robinhood is not a charity. They need to make money or they go out of business eventially. So they sell order flow to high frequency trading firms. A letter from one of the founders last year explained how this works:

The revenue we receive from these rebates helps us cover the costs of operating our business and allows us to offer commission-free trading. Robinhood earns ~$0.00026 in rebates per dollar traded. That means if you buy a stock for $100.00, Robinhood earns 2.6 cents from the market maker. Other brokerages earn rebates and charge you a per-trade commission fee.

The hope here is that passing these trades along to the HFTs will allow for better prices than they would on another exchange but it’s hard for customers to know for sure if they’re truly getting better execution.

These firms can also make money on interest rate spreads for what they pay out on cash balances, margin loans, fund fees (for the ones that have their own line-ups) and financial advice. They’ll figure something out.

I’m surprised the market was surprised. Most of the carnage has come following this week’s announcements but these stocks have all been in a state of drawdown for over a year now:

I assumed everyone knew where these fee wars were heading. Maybe the market didn’t think it would happen this fast. It would seem to me not all, but many, investment firms are going to have difficult business decisions to make in the years ahead as their margins slowly erode.

I’m not that worried about the behavioral ramifications of this. A number of people have commented on the idea that completely taking away the barriers to entry and exit when trading stocks or funds will lead to worse investor behavior.

My take is those who are going to panic/over-trade are going to panic/over-trade whether they’re paying $19.95, $4.95 or nothing on their trades. Plenty of investors overtraded and made behavioral errors before discount brokerages existed. I don’t think zero commissions are going to turn us all into a bunk of junkie traders.

I actually think investor behavior is slightly improving on the margins.

There has never been a better time to be an individual investor. I’ve probably said or typed this three-dozen times over the past 4-5 years but it continues to be true (and continues to get better).

Fund fees get lower by the year. We now have access to more strategies, fund types, and geographies at a low cost than any investor class in history. Technology in the space has improved by leaps and bounds. And the frictions of creating and managing a portfolio continue to fall.

These are all wins for the investment consumer at the expense of the investment producer (Wall Street).

Source:

Stay the Course by John Bogle

Further Reading:

Trading Costs and the New Market Averages

1What’s the right name for this decade? Can we start calling it the tens? I’m excited for the next decade when the 20s makes an appearance in the lexicon.

2Or if there was a bubble in that space the public markets certainly aren’t taking the bait.