A reader asks:

I cannot predict the future, but if I needed to assign a probability that in the next 10 years the United States joins many other advanced economies in the negative interest club, I would put it at 75 percent or better.

My question is: Where can someone such as myself put my retirement money if indeed we are headed to negative interest rates here in the US?

First of all, it’s impossible to know exactly what to make of negative interest rates in government bonds around the globe for the simple fact that it’s never happened before. There is no historical precedent for this. Anyone who tells you they know how this will transpire is a maniac.

Predicting interest rate moves is notoriously difficult but I’m increasingly coming around to the idea that it’s only a matter of time until the U.S. joins much of the developed world with negative nominal interest rates in government bonds. We discussed on the podcast this week:

The 10-year treasury yield began the year at roughly 2.7%, so it’s fallen about 1% this year already:

Rates still haven’t taken out the lows of 2016 but it’s closer than anyone could have imagined at the start of the year.

The Fed still has its short-term interest rate pegged at a range of 2.00% to 2.25%. If I had to guess (and this is only a wild guess), the only way we would see negative rates would be during the next recession, whenever that may be. The fact that other countries are already there would seem to make it easier for it to happen in the U.S.

This is worth considering if for no other reason than scenario analysis can be helpful when planning for the future. That way you’re not as surprised when you’re surprised by what happens.

Some thoughts:

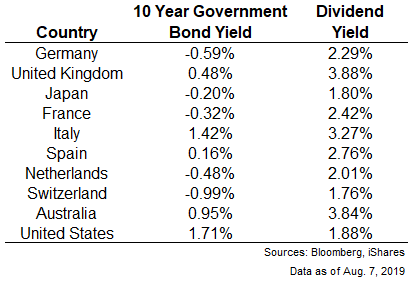

You have to accept volatility in some form to earn decent returns on your capital. Here’s a look at 10 year government bond yields in much of the developed world in comparison with the dividend yield1 on the stock market in those countries:

I’m not suggesting you should consider stocks as a perfect alternative to bonds. That’s too big of a leap. Stocks and bonds are inherently different asset classes with much different risk profiles. There are other places you could chase yield if you’re so inclined (corporate bonds, mortgage bonds, junk bonds, preferred stocks, etc.).

But yields in those assets are also falling and all fixed income, save for TIPS, suffers from the same big risk — inflation.

Sooner or later, these rates are going to force investors in theses countries to (a) wildly readjust their return expectations or (b) become more willing to accept volatility in their portfolio.

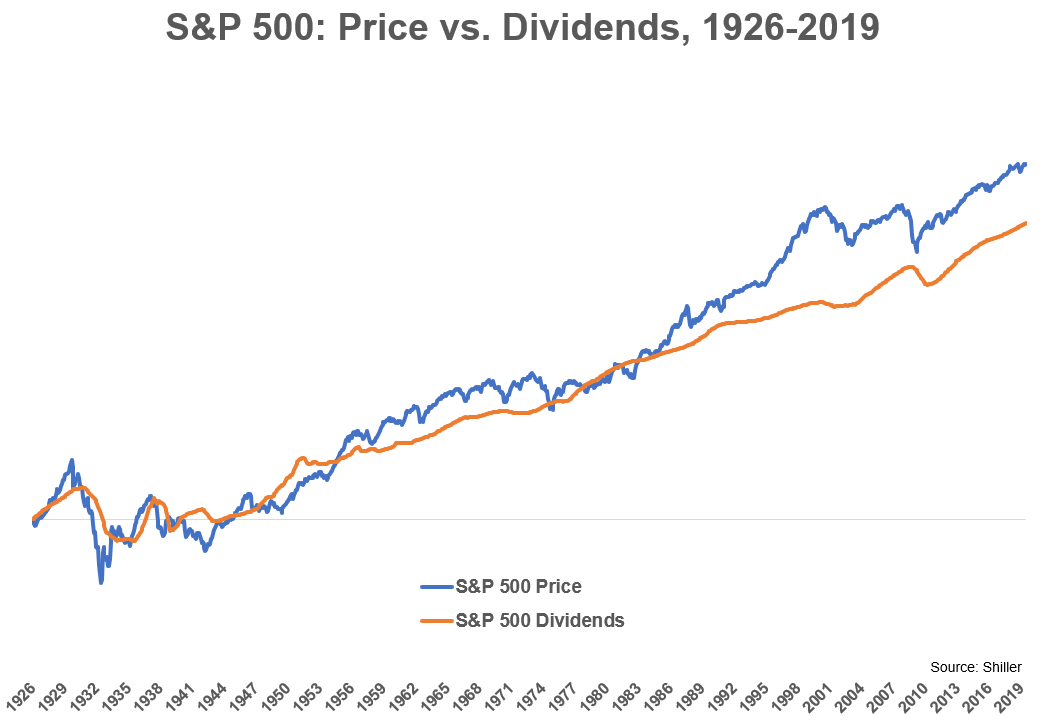

Re-thinking stock market volatility. Dividends are one of the most underappreciated aspects of the stock market. They offer investors a unique income stream if you’re able to get over the mental accounting of separating price from dividends in the total return calculation.

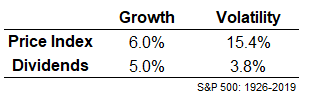

This chart shows the growth of the S&P 500 in terms of price and dividends since 1926. You can see a much smoother ride in dividends. Here’s the breakdown:

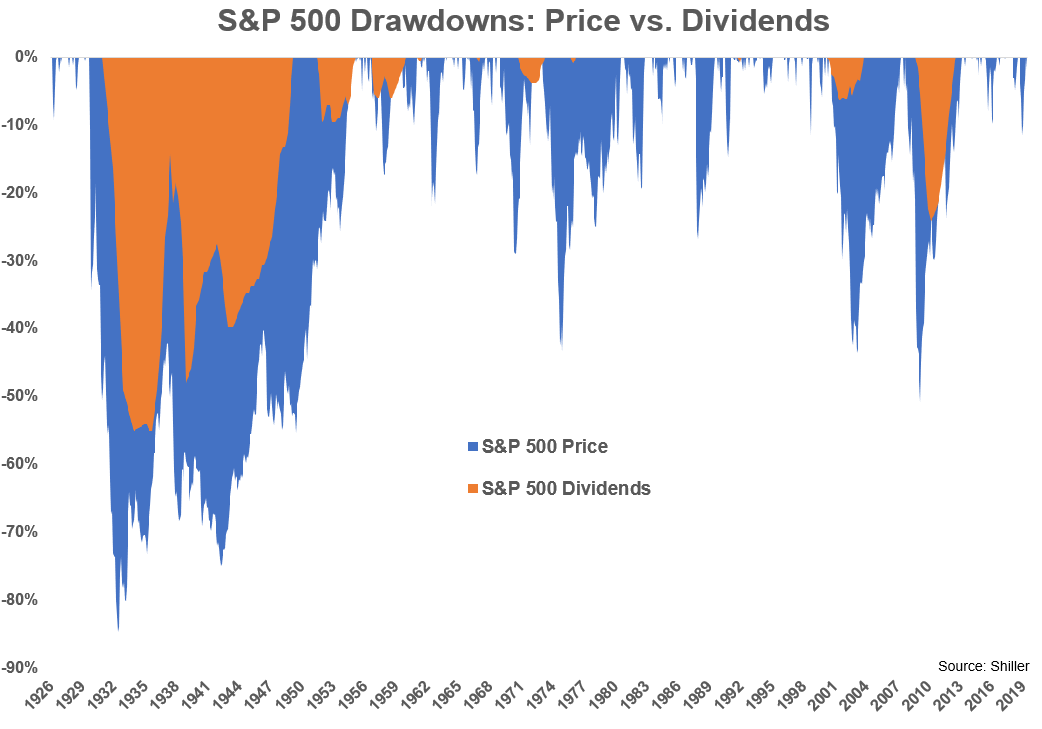

The growth of the two subsets of stock market returns is similar but the volatility of prices were four times higher than the volatility of dividends. Here’s another way to view this:

Dividends don’t fall nearly as much as stocks when the market gets crushed. This is another way of saying prices can go far beyond the fundamentals. Taking out the Great Depression, there has only been a single instance where dividends fell double-digits (2007-2009). And that drawdown of 24% pales in comparison to the 56% or so shellacking in prices.

Stock market dividends are one of the few income streams that have consistently delivered rates of return well over the inflation rate over time. Since 1926, S&P 500 dividends have grown at a rate of roughly 5% per year while CPI has grown at around 2.9%.

Obviously, that higher growth in dividends has come with higher volatility than what an investor could expect to see in the bond market.

But if you’re able to think about the dividends from the stock portion of your portfolio as a source of income, they are much more stable than the price movements in the stock market.

Think about bonds in terms of protection, not yield. The stock market becomes more important when rates are on the floor but that doesn’t mean you can forsake bonds or cash altogether.

Most investors think about bonds in terms of yield or income. And why shouldn’t they? The vast majority of returns in bonds over time come from the starting yield, not price appreciation.2

In a negative interest rate world, you have to change the way you think about bonds. Bonds have always acted as a shock absorber to stock market declines but this becomes even more important when the yield is more or less taken out of the equation.

Bonds can provide dry powder to rebalance into the stock market or pay for current expenses when the stock market inevitably goes through a nasty downturn. Bonds keep you in business even if they don’t provide high returns as they have in the past.

Understand this is not an easy world to invest in. No one knows the implications of a negative yield world because it’s never happened before to this extent. Market environments are always different but this one might be even more so than most.

There are no easy solutions. To earn higher returns, you’re going to have to accept more volatility in some form or another. To have more stability, you’re going to have to accept lower returns.

This risk-reward relationship has always been in place but the returns paid for stability are drastically lower than they’ve been in the past. If bond rates in the U.S. go negative there can still be some decent price returns squeezed out in the meantime. But eventually, yield wins out and long-term bond investors will see paltry returns on their capital.

I wish investors could earn easy 5-6% risk-free rates of return but it appears those days are behind us. You have to invest in the markets as they are, not as you wish them to be.

This may require a re-framing in how investors think about risk in their portfolio.

Further Reading:

My Questions About Negative-Yielding Debt

1Using the iShares country ETFs as a proxy.

2Jake from EconomPic estimated the portion of returns from price (falling rates) on the Barclays Aggregate Bond Index since 1973 to be just 6%. That means 94% came from the starting yield.