In my last piece we looked at how things are going in the bond market. In summation — rates are up and bonds are down.

There are plenty of market prognosticators who are more informed than me predicting interest rates will rise further from here. The 10-year treasury yield currently stands at 3.3% or so. I’ve seen predictions that peg the 10-year at 4%, 5%, even greater than 6% yields before all is said and done.

That’s one scenario and it’s certainly a possibility. The economy could overheat. The Fed could continue to raise rates. Inflation could get out of control. Housing could go nuts. All of these things have happened in the past and could potentially happen again.

In this scenario bonds would have a tough go at it. Interest rates are much higher than they were just a couple years ago, but another 100-300 basis point increase in yields would be painful in bond land, especially if it’s coupled with higher inflation.

I find it’s always helpful to look at a variety of scenarios when thinking through any investment outlook because no one knows what the future holds. The case against bonds is one scenario.

To see the other side of this one, I want to make the case for bonds to think through what that scenario could look like.

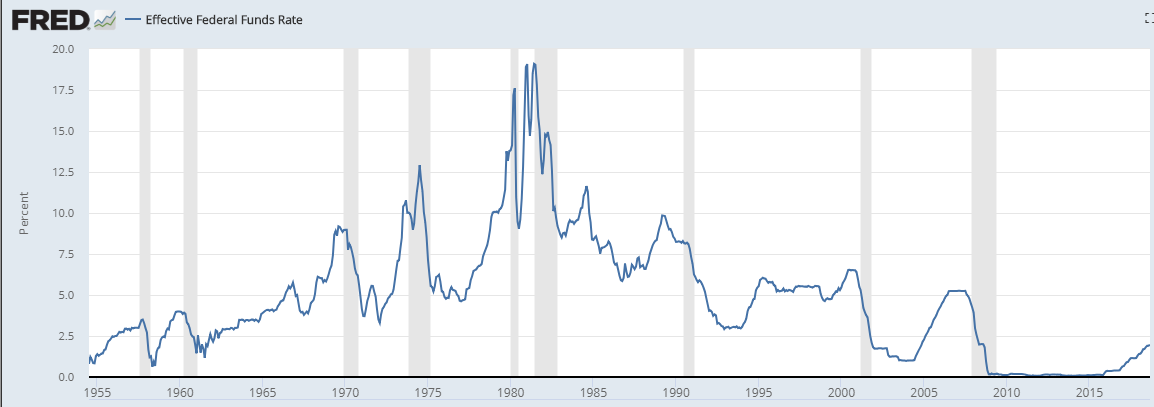

This is a historical graph of the Fed funds rate, the short-term interest rate the Fed uses for monetary policy:

Rates are still coming off the floor and there’s no historical precedent for that so where things go from here is anyone’s guess. The Fed may continue to raise rates for the foreseeable future.

There’s also the possibility the economic expansion slows down, the Fed raises rates too fast, or some other economic catastrophe comes out of left field that causes Jerome Powell and crew to stop hiking or even lower rates yet again.

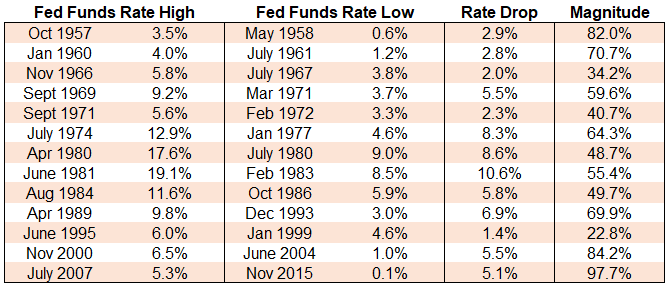

To gain a better understanding of what a potential rate drop could look like, I calculated the previous rate drops using historical Fed funds data1:

The average rate drop since the late-1950s has been 5.2%. The reason that number is so high is that the starting yields were so much higher in the 1970s and 1980s. So I also looked at the magnitude of the rate drops which shows how much the Fed lowered rates as a percentage of the peak yield. The average drop was 60% from the previous peak, with a range in the decline from a low of 23%1 to a high of 98% (hello Great Recession).

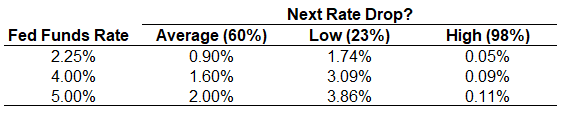

The current Fed funds rate is just 2.25%, still low by historical standards. To show how things would look from a future Fed rate drop, I took the average, low, and high fall in rates to give a range of outcomes from the current Fed funds rate, a 4% rate, and a 5% rate in the event we get to those levels:

A few years ago many Fed watchers wondered if they needed to raise rates simply to give themselves a lever to pull in case of emergency in the next economic downturn. Well, they’ve given themselves some breathing room but it would be crazy if another downturn were to hit in the coming years which forced them to unwind all the hikes they’ve done in this cycle.

If the economy were to contract, you would expect stocks to fall since recessions aren’t a great thing for the stock market. Were stocks to fall, you would expect to see a flight to the relative safety of high-quality bonds. The Fed only controls the short end of the yield curve but under these conditions, one would assume bonds would do well from a combination of falling rates and increased fund flows into the asset class from investors who still have scars from the last financial crisis.

It may seem at odds with the current environment to start thinking about the Fed lowering rates again considering they’re in the midst of a hiking cycle. There’s still talk of the two more rate hikes next year. Avoiding excesses versus snuffing out the expansion is a balancing act I wouldn’t want to perform.

Things are still humming along. The unemployment rate hit 3.7% last week, the lowest number since 1969.2 It feels unnatural to begin thinking about the other side of an expansion, low unemployment, and high stock prices since it was so difficult to work our way back to this point.

Is it a little early to be talking about rates falling? Most likely.

I’m not sure when the next recession will hit or what the path of interest rates will look like in the meantime.

Bonds could still be setting up for more pain in the short-to-intermediate-term if rates continue to rise and economic growth/inflation get out of control. There’s a case to be made for avoiding bonds in the years ahead but that case was much stronger when rates on the 10-year were sub-1.5%. There’s a bigger buffer now, especially in the short-to-intermediate maturity range, in terms of the yields.

This is probably a couple years too early but there is a case you could make for bonds to rally.

As with most things in the markets, the timing is the tricky part of this equation.

Further Reading:

What Happens to Stocks and Bonds When the Fed Raises Rates?

1Some of these cycles were harder to pinpoint than others because rates were being raised and lowered at a ridiculous pace in the 1970s and 1980s so I did the best I could to break out the individual rate drops.

2The shallowest rate drop came at the tail end of the dot-com bubble. I still can’t believe the Fed cut rates at that time because of Y2K fears but that’s partly why it happened.

3The lowest on record is 2.5% in 1953.