Ever since the financial crisis investors have been bombarded with books, blog posts, articles and advice about how to survive the next bear market/Lehman Brothers/black swan/recession/subprime/1987/big short moment in the markets.

And don’t get me wrong, preparing yourself mentally for market downturns can be a helpful exercise. These things are inevitable so planning for a wide range of outcomes that includes the potential for large losses in risk assets is a decent way to ensure that you don’t panic when markets do fall.

But there’s another risk in the markets that most investors don’t spend too much time worrying about — a melt-up in prices.

It would seem to me that all of the ingredients are in place for a potential U.S. equity bubble. Interest rates are extremely low, central banks around the globe are almost accommodative across the board, there is a substantial need for returns from pensions and retirees and a general lack of alternatives elsewhere to invest. That doesn’t mean it has to happen, but the pieces are in place for upside volatility, something very few investors believe could occur these days.

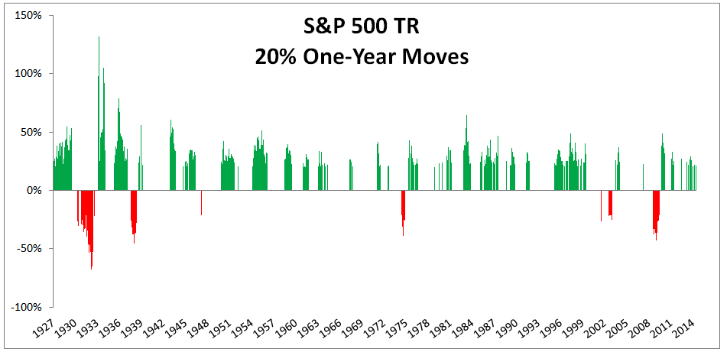

In fact, if you look back historically at how stock markets have generally performed, they are much more likely to rise substantially than fall substantially in a given year. My colleague Michael Batnick ran those numbers this week and found that since 1926, “U.S. stocks were nearly six times more likely to be up twenty percent one year later than they were to be down twenty percent.” Here’s his chart:

Very few investors would consider further gains in the stock market to be a risk, but there is always the chance that greed can take over your decision-making process when unexpected gains occur. The other side of those gains can be painful if you’re not careful. The switch can flip from the fear of being in to the fear of missing out pretty quickly in the markets.

In a recent white-paper, Michael Mauboussin explains that one of the traits that great investors share comes from knowing the difference between information and influence:

…investing is an inherently social exercise. As a result, prices can go from being a source of information to a source of influence. This has happened many times in the history of markets. Take the dot-com boom as an example. As internet stocks rose, investors who owned the shares got rich on paper. This exerted influence on those who did not own the shares and many of them ended up suspending belief and buying as well. This fed the process. The rapid rise of the dot-com sector was less about grounded expectations about how the Internet would change business and more about getting on board. Negative feedback ceded to positive feedback, which pushes a system away from its prior state.

Great investors don’t get sucked into the vortex of influence. This requires the trait of not caring what others think of you, which is not natural for humans. Indeed, many successful investors have a skill that is very valuable in investing but not so valuable in life: a blatant disregard for the views of others. Success entails considering various points of view but ultimately shaping a thesis that is thoughtful and away from the consensus. The crowd is often right, but when it is wrong you need the psychological fortitude to go against the grain. This is much easier said than done, especially if it entails career risk (which is often the case).

Other than a “blatant disregard for the views of others,” here are a few more thoughts on surviving a potential melt-up:

Don’t change your strategy. The worst time to completely change your strategy is following huge gains that you missed or huge losses that you didn’t. It’s rarely a good idea to do a portfolio overhaul during emotionally-charged markets.

Stay within your comfort zone. You never want to invest in new or exciting products or strategies just because everyone else is doing it. You always have to know what you own and why you own it, but this becomes even more important when markets are screaming higher.

Avoid chasing yield and substitutes. I’m looking at you bond substitutes.

Don’t own more stocks than you’re comfortable holding during a bear market. My rule of thumb for most long-term investors is never own more stocks in a bull market than you’re comfortable holding during a bear market.

Have a plan. You always have to have an idea about when you will buy or sell or do nothing in a number of different market scenarios. Take yourself out of the equation as much as possible.

Above all else, know yourself. How you choose to invest should always come down to the type of person you are and what you can and cannot handle in the markets in terms of risk.

To be clear, I’m not predicting a melt-up and saying it has to happen. But you always have to prepare for the possibility that something like this could be in the cards.

Although I do get the sense that investors today don’t want another bubble. They’ve been burned twice in the past two decades already so that euphoria hasn’t quite kicked in just yet, even as prices have continued to rise.

It would be interesting to see what would happen if investors became optimistic for once since the financial crisis.

Sources:

Reflections of the 10 Attributes of Great Investors (Credit Suisse)

The Next Twenty Percent (Irrelevant Investor)

Further Reading:

How to Preserve Capital During a Bear Market

Now here’s the stuff I’ve been reading lately:

- Paper trading is obsolete (Abnormal Returns)

- Here’s a bunch of data to show how great the world is doing (Tyler Hogge)

- Charley Ellis on the index revolution (Institutional Investor)

- The power of negative thinking (A Teachable Moment)

- How volatile is the market compared to history? (Steward Wealth)

- Why Twitter is a marketplace of ideas (Fortune Financial)

- Nothing recedes like success (Reformed Broker)

- Auto loans aren’t a repeat of the subprime crisis (Prag Cap)

- Invest & relax (Evidence-Based Investor)

- The upside of losing half your money (Motley Fool)