Once the shutdowns began in mid-to-late March and the economy was effectively put on ice, predictions began pouring in about the potential unintended consequences.

Some people assumed there would be a replay of the Depression Babies which saw an entire generation of people change their spending and saving habits to a more frugal lifestyle following the epic meltdown in the Great Depression.

It was impossible to be certain about anything at that point but one of my strongly held opinions at the time was the eventual continued strength of the U.S. consumer. If there’s one thing we can agree on in this country it’s spending money.

We consume.

Even with that strongly held view, I wouldn’t have predicted just how resilient the consumer would be in their willingness to keep spending.

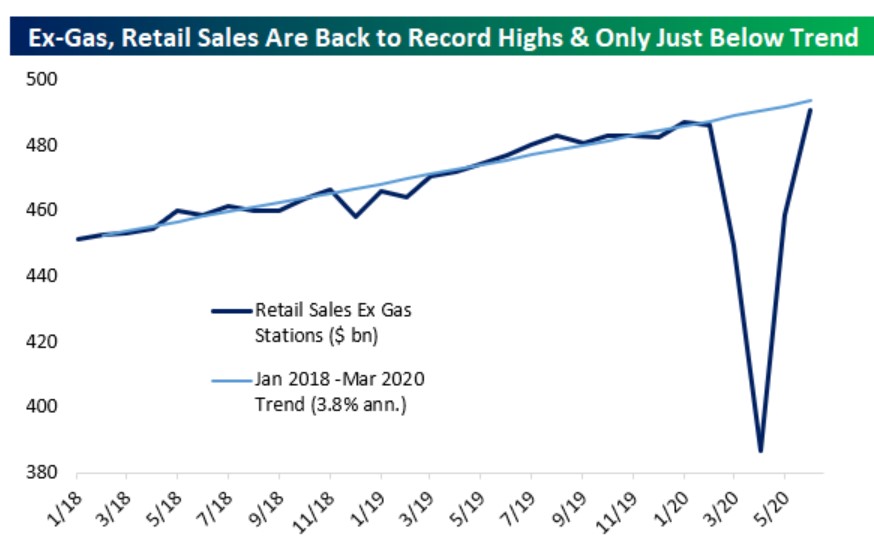

Take a look at the retail sales ex-gasoline stations (which are driven exclusively by the price of oil) via the folks at Bespoke Investment Group:

Retail sales are now at all-time highs and are up nearly 1% from the January peak.

Obviously, this spending had been aided by colossal government stimulus but it’s amazing how people have continued to spend even as we live through an unprecedented economic situation.

We’re not out of the woods just yet when it comes to this crisis but even if we take two steps forward and one step back for a while I wouldn’t bet against the American desire to spend.

So how did we get here? How did the consumer come to dominate the biggest economy on the planet?

A number of major events and shifts in the way the global economy operates created the beast that is the U.S. consumer.

The Nature of Work Changed

In the late-19th century more than 80% of the labor force was employed in work that was hazardous to their health and generally unpleasant.

In 1901, one out of every 400 railroad employees were killed on the job while one out of every 26 was injured.

The average worker spent 10 hours a day on these difficult jobs and worked for six days a week.

There was also little mobility among the working classes. In 1870, nearly three-quarters of those working in manual labor attained no upward mobility in their career even after two decades on the job.

People didn’t have time to spend money even if they had it and there really wasn’t much to spend it on anyway. Life was hard and there were few material possessions or experiences to spend your money on in the late-19th and early-20th centuries. And even if there was, few people could afford them.

It wasn’t until the 1920s that average workdays went down to eight hours and that was still six days a week. It took until the 1940s for the standard five days per week to take hold.

Another reason most people didn’t consume back in the day is because it was so difficult to do so.

The majority of the country didn’t have access to much beyond a general store before Sears and Roebuck rolled out their mail-order catalog to rural areas in the early-1900s.

The Sears Wish Book offered rural households the ability to choose from more than 200,000 items at a savings of roughly 50% of what they would spend at their local store.

More leisure time and the ability to finally have a wider selection of cost-effective goods gave the population their first taste of consumerism.

The Roaring Twenties

Following World War I and the Spanish flu pandemic of 1918 people were looking for a pressure release valve. They just wanted to have a good time and spend some money after living through years of pain and stress.

Enter the Roaring Twenties.

Innovation ushered in the second phase of consumerism by offering households new technologies previous generations could only have dreamed of.

There was so much more to buy and so much more to do.

Refrigerators, washing machines, dishwashers, irons, private indoor toilets, electricity throughout the house, showers, central heating and automobiles all became more prevalent for most households.

Motion pictures and the radio offered large groups of people genuine entertainment options.

The assembly line not only brought higher wages for manufacturing workers but the cost of an automobile fell by almost 65% in the first two decades of the 20th century. The number of cars on the road soared from a little more than 13,000 in 1900 to 3 million by the early 1920s and more than 44 million by 1950.

To pay for all of this stuff the Roaring Twenties also introduced installment payment plans. The phrase “buy now, pay later” became part of the popular nomenclature during this time.

Robert Gordon estimates by the end of the 1920s consumer credit financed 80-90% of furniture sales, 75% of washing machines, 65% of vacuums, 25% of jewelry and 75% of radios.

Previous generations attached a social stigma to borrowing. The 1920s chipped away at this idea as people purchased products that didn’t exist for those generations.

And while the country as a whole achieved a level of prosperity from 1923-1929 like never before, farmers were decimated. The depression of 1920-1921 cut the price of farm products in half and they regained just a fraction of those losses by the end of the decade. Incomes for farmers fell more than 60%.

The end of agriculture as the dominant career choice in the early part of the 20th century led to an urbanization boom. The first Sears store opened in Chicago in 1925. By the time the expansion was coming to an end in 1929 they were up to 300 stores, mainly in big cities.

The Great Depression

One of the reasons the worst economic downturn in our country’s history led to a generation of cautious, frugal consumers is because there was no social safety net to protect the general public.

It’s estimated more than nine thousand banks went under. The unemployment rate reached around 25% at the depths of the depression but stayed in the double-digits for the remainder of the 1930s.

The majority of the population had no financial backstop.

Even though all of the effects weren’t felt right away, the programs established in the New Deal by FDR would help protect the unemployed, the investor class, workers, the young and the old like never before.

The government established the Social Security Administration, the SEC, the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, the Civil Works Administration, the Civil Conservation Corps, the Civil Works Administration, the Agricultural Administration Act and more.

Although the economy stagnated throughout the 1930s, productivity skyrocketed over this awful decade. Output per hour worked increased by an estimated 12% from 1900-1910, 8% from 1910-1920, 21% from 1920-1930 and a stunning 41% from 1930-1940.

A combination of fewer workers and better technology increased efficiency during the worst economic crash in history.

The economy wasn’t awoken from its Great Depression slumber until WWII spending kicked into high gear.

World War II

The majority of the gains from the prosperous Roaring Twenties went to the wealthy class.

By the time the stock market and economy peaked in 1929, just 2.3% of American families had incomes of more than $10,000 a year while more than 70% of families lived on less than $1,000 a year. Nearly 60% of American families had incomes that placed them below the poverty line.

The massive defense spending from the war and GI Bill more or less created the middle class.

The U.S. economy was almost three times as large in 1945 as it was in 1939 because of the wartime spending. Incomes also exploded, up almost 90% in this same period. Even after accounting for inflation, the disposable income of all Americans rose by almost 75% from 1929 to 1950 and the majority of the gains went to the lower and middle classes.

Frederick Lewis Allen describes the sea change from the Great Depression to post-WWII:

What do these figures mean in human terms? That millions of families in our industrial cities and towns, and on the farms, have been lifted from poverty or near-poverty to a status where they can enjoy what has been traditionally considered a middle-class way of life: decent clothes for all, an opportunity to buy a better automobile, install an electric refrigerator, provide the housewife with a decently attractive kitchen, go to the dentist, pay insurance premiums, and so on indefinitely.

Once the war was over people were ready to settle down in the suburbs, start a family and begin the American dream, which had been destroyed during the previous 20 years or so.

The New American Dream

Housing starts fell from one million a year to fewer than one-hundred thousand from the onset of the Great Depression through the end of the war.

A federal housing bill, a baby boom, and large number of soldiers returning from war looking to settle down helped the number of new single-family homes built grow from 114,000 in 1944 to 937,000 by 1946 and 1.7 million by 1950.

The post-WWII boom meant owning a home and buying material possessions became the embodiment of the American dream. And the growing affluence of the country during the 1950s meant most Americans could afford a house on just one income.

The number of families moving into the middle class was increasing at a rate of more than one million households a year by the mid-to-late 1950s. Virtually half the country was in the middle class by the end of the 1950s and consumerism was one of the main offshoots of this.

Fortune reported in 1956, “Never has a whole people spent so much money on so many expensive things in such an easy way as Americans are doing today.”

Credit cards opening up to a large swath of the population in the 1950s also planted the seed for consumers to ramp up their borrowing.

Globalization

The economic tranquility of the 1950s and 1960s is looked back fondly by many people because of the burgeoning middle class in America but it’s possible that period was an anomaly.

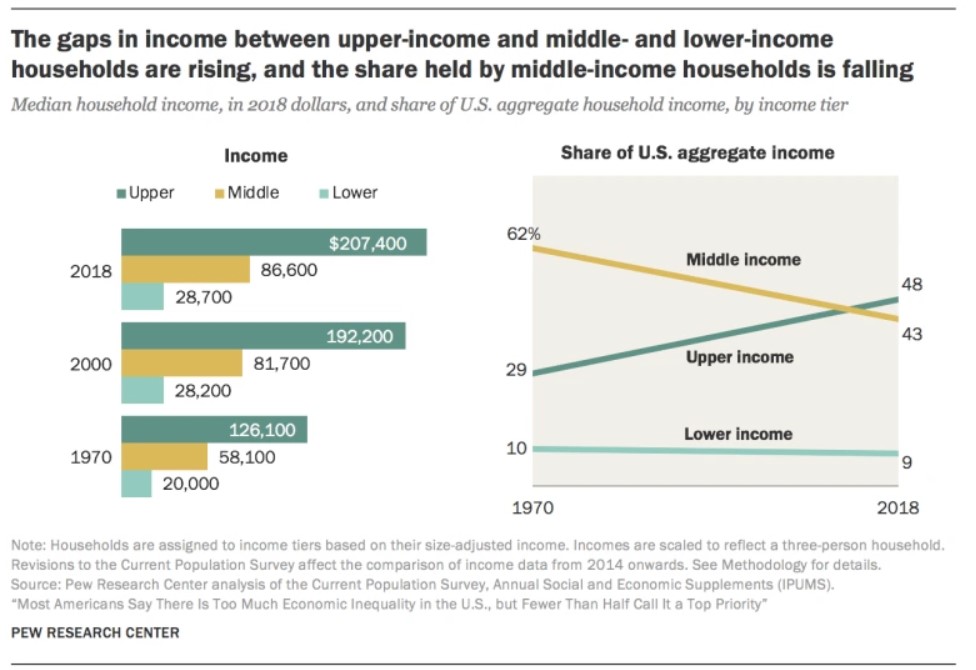

Inequality persisted before WWII and has come back with a vengeance in the decades following the post-war boom.

Incomes have stagnated for a large percentage of the population over the past 50 years or so while the gains have gone mostly to the highest-earning households:

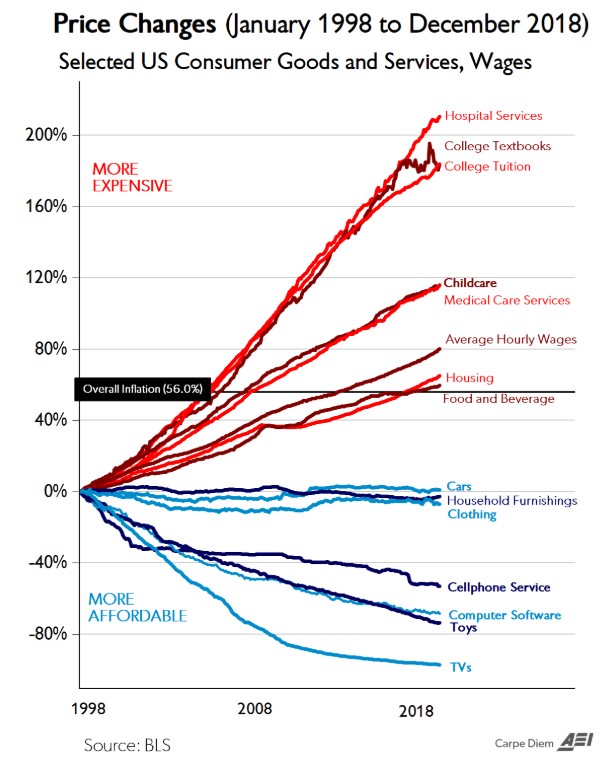

This hasn’t slowed our appetite for consumption even as we’ve experienced inflation in many necessities but deflation in the things we desire:

The fall of the Berlin Wall and globalization that’s ensued in the intervening decades have made it more difficult for many in the lower and middle classes.

Previous generations could find jobs out of high school for decent-paying jobs with good benefits that allowed them to support their families and buy affordable housing. Those opportunities are now few and far between as most of that work has been shipped overseas to places with lowers wages or eaten up by advances in technology.

In exchange for those jobs, we’ve gotten back cheaper TVs and computers and stuff to buy.

Consumer spending now accounts for roughly 70% of the U.S. economy.

We spend and we borrow and we enjoy material possessions and experiences.

Are things going to change because of the pandemic? Certainly.

Are consumers going to become more frugal with their spending habits because of this crisis?

I wouldn’t bet on it.

Sources: