It seems bizarre to worry about inflation during the sharpest, more severe economic contraction of our lifetime.

But the sheer amount of government spending and monetary policy being instituted by the Federal Reserve means it’s something that’s on people’s mind as a potential risk in the not-too-distant future. The “worry” is once the virus is contained the economy could potentially overheat through a combination of pent up demand and government spending.

My initial read on this is if we do get inflation from all of this spending that’s a good thing — it means we beat the virus and things are back to normal (if there is such a thing).

The Fed would have a much easier time fighting inflation than the current predicament.

Here’s former Fed chair Janet Yellen in the WSJ discussing this idea:

Bigger federal borrowing needs will make it costly for the Treasury should interest rates eventually rise. “If the economy recovers and inflation is a problem, that will be the test,” says former Fed Chairwoman Janet Yellen. That isn’t a problem now. If it ever is, she says, “I think the Fed is going to win out on that.”

You have to be thinking 12 moves ahead to start planning for higher inflation at this point but there are likely some areas of the market that would benefit more from an inflationary spike than others.

Earlier this week I posited that low interest rates may be the simplest explanation for the stock market’s resiliency. A few people pushed back with the fact that rates have been low in Japan and Europe as well and their markets haven’t been quite as strong.

Japan is on another planet when it comes to market relationships in general but there is an explanation for this. Because of the differences in the sector make-up of the underlying markets, U.S. stocks are more heavily weighted towards growth stocks while European and Japanese stocks are more in the value camp.

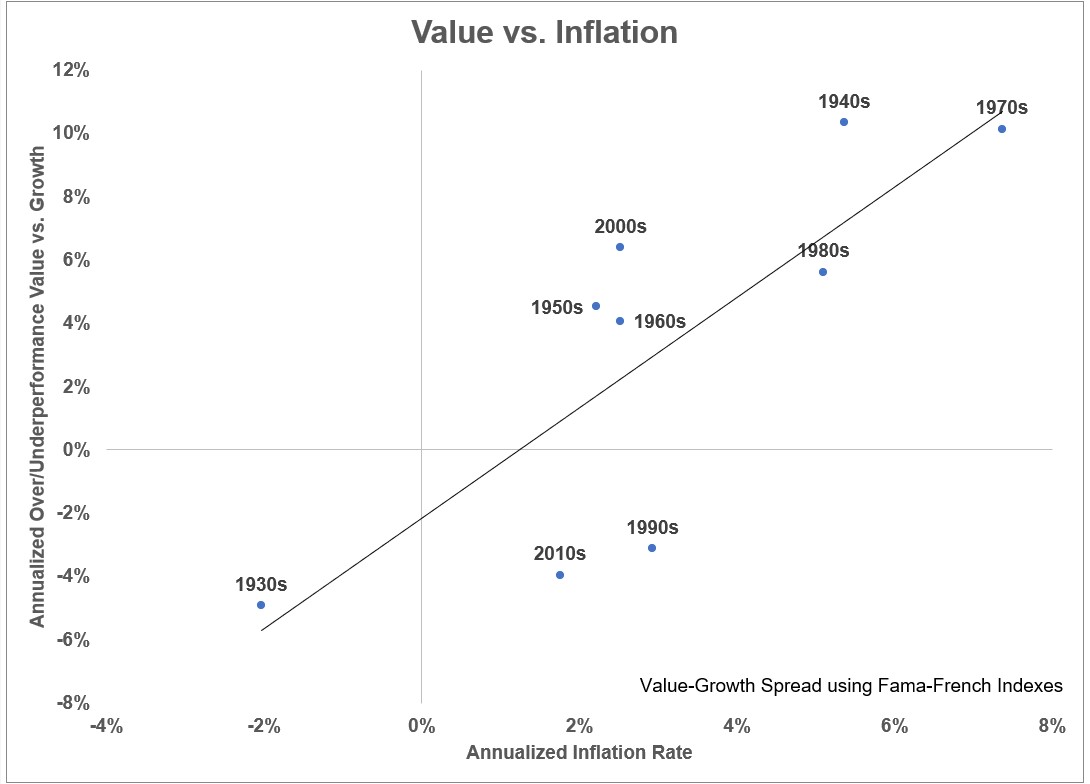

In a low rate, low inflation world, growth stocks tend to perform better while value stocks tend to do better when inflation is higher:

Think about growth stocks like they are a bond. The reason inflation is such a big risk for bondholders is because the purchasing power of your fixed rate income payments is eroded over time by inflation.

The same thing is true of promised future growth in revenue or profits for growth stocks. Value stocks likely already have cash flows now that will likely decrease into the future. Thus, higher interest rates should hurt value stocks less than growth stocks since the higher hurdle rate makes future growth not worth as much.

William Bernstein described this relationship in a piece from his blog in the early-2000s called Who Killed Value:

The original Fama-French paper covered a period of very high inflation, the years 1963-1990, and consequently showed a robust value effect. Towards the end of that period, interest rates and inflation commenced a long and powerful decline, which continues to this day—just the sort of environment expected to favor growth stocks. […]

In an investing state-of-nature—say a Grover Cleveland world of unfettered capitalism, gold standard, and zero inflation—growth and value stocks have equal returns. The slope of HmL on inflation is 1.1, so each one percent of inflation adds about one percent of HmL. Thus, if inflation stays at 2% to 3%, we can expect an HmL [value premium] of similar size. And not coincidentally, the HmL for the full 74 years from July 1926 to June 2000 was 3.36%, while inflation was 3.12%. As long as there is fiat currency, there will be inflation; in the long-run, the value premium seems assured.

The most interesting feature of these data is that HmL is much more dependent on the absolute level of inflation than its rate of change. Why, in an efficient market, does a statically high (or low) rate of inflation produce high (or low) HmL? After all, one would assume that a static high or low inflation rate would be discounted into prices. This gets to the heart of the value premium. For if markets are truly efficient, this premium can only be compensation for some sort of risk. An alternative explanation is that markets are not efficient in the value dimension; that in fact, investors overestimate the magnitude and persistence of earnings increases for growth stocks, thereby overpricing them, and underpricing value stocks.

You can see from the chart that the middle ground of 2-4% inflation has lead to mixed results in the value vs. growth leadership so this relationship isn’t foolproof. But inflation isn’t the only factor necessary for value to outperform.

The growth rates of the biggest tech stocks could also become so inflated that these companies can’t possibly hope to live up to inflated investor expectations.

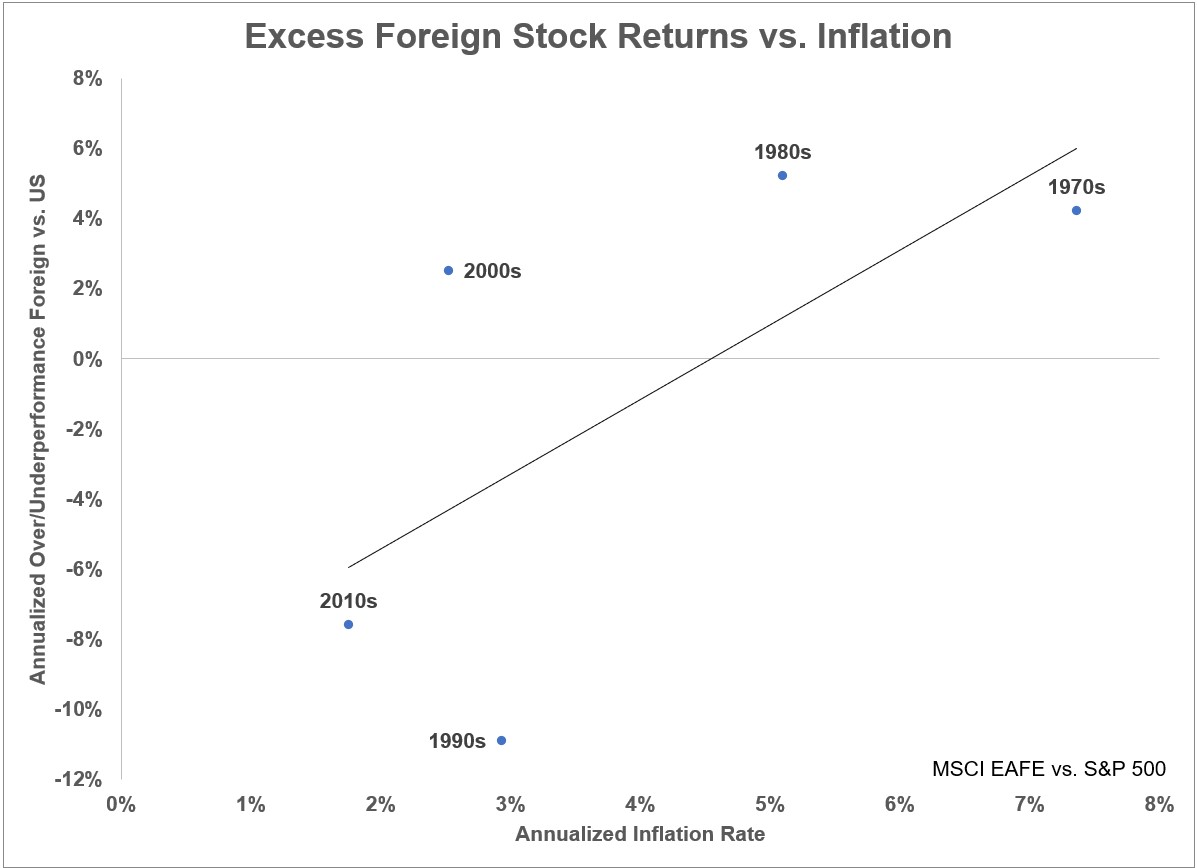

Now back to Japan and Europe — foreign stocks have a similar relationship to inflation:

Foreign developed stocks have tended to outperform U.S. stocks when inflation is higher and underperformed when it is lower.

There are far more factors at play with this relationship (including the direction of the U.S. dollar) but this may help explain why lower rates haven’t led to better stock market performance overseas. Those countries may need higher rates (caused by higher inflation) to outperform regularly.

Again, not a perfect relationship but this makes sense when viewed through the lens of how growth and value stocks typically perform in different inflation environments.

You may have noticed I’ve been working through a number of theories in my writings of late.

I wrote about how the Fed could be altering the risk-return spectrum of U.S. stocks and valuations. Then there’s the idea that interest rates may be causing the confusing moves in the market. And how the biggest stocks in the S&P 500 are making it harder for stocks to fall as far as some investors would like.

These theories aren’t all-encompassing to explain what’s going on in the markets because you can never narrow these things down to a single variable. There are simply too many moving parts when it comes to reasons markets do what they do.

But I find it helpful to keep an open mind when it comes to market moves that sometimes make no sense. Markets don’t always have to make sense but often times there are underlying reasons that can help provide some context so you’re not just beating your head against the wall.

Further Reading:

Occam’s Razor on Interest Rates and the Stock Market