The 1980 NBA Finals featuring the Los Angeles Lakers and Philadelphia 76ers was the first time the three-point line was in effect for the championship series.

The Lakers won in six games behinds a strong performance from rookie Magic Johnson (42 points, 15 rebounds, and 7 assists in the closing game).

Over the course of these six games, the two teams combined for a single three-point field goal. That’s not one three per game or per team but for all six games for the two teams combined.

Last year, Klay Thompson of the Warriors hit 14 threes in a single game.

The game as it’s played today with spacing, drive-and-kick offenses, new rules, and three-point shooting is almost indiscernible from the way it was played in the past.

This makes it nearly impossible to compare teams, players, or records across different eras.

But that doesn’t stop us from trying.

Jordan vs. LeBron could carry a slow news day on sports talk shows for the next 5 decades or so.

Financial markets are similar in that comparing track records and performance numbers is nearly impossible because you have to take into account the market environment, competition, regulations, fundamentals, and economic backdrop.

There aren’t too many Jordan vs. LeBron debates on the financial markets so Michael, Josh and I decided to hash this out when I was in New York recently:

A few months ago I wrote about my choice for the most impressive investment track record of all-time, settling on Warren Buffett. Much like Shawshank being listed as the greatest movie of all-time, no one is going to argue with you if you go with Buffett.

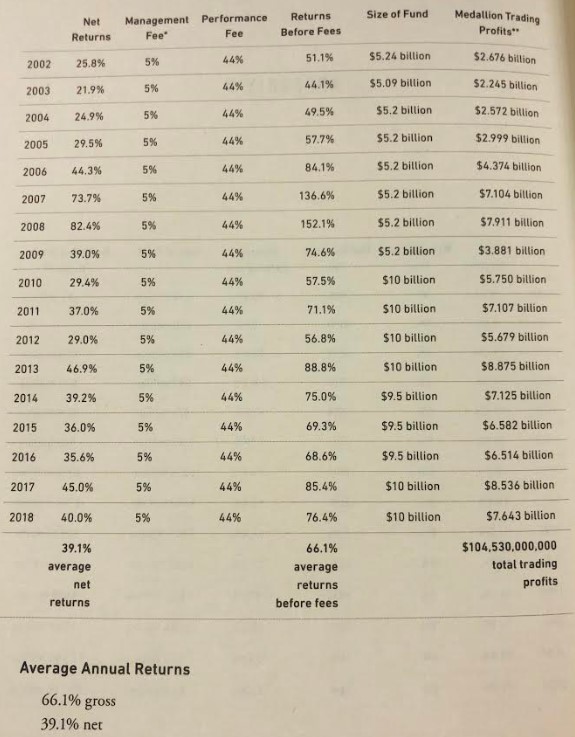

After reading about Jim Simons and his ridiculous track record at Renaissance Technologies I may need to reconsider:

Those returns have come since 1988. I’m still having trouble wrapping my head around exactly how they did it (listen to our chat with Greg Zuckerman for more on this).

Jason Zweig wrote a lovely tribute to Benjamin Graham discussing what he learned from the father of value investing after updating Graham’s classic The Intelligent Investor in 2003. Zweig described the five types of brilliance Graham exhibited:

- Intellectual brilliance

- Financial brilliance

- Prophetic brilliance

- Psychological brilliance

- Explanatory brilliance

His brilliance extended beyond the markets. Before graduating from Columbia, Graham was offered teaching roles in mathematics, philosophy and English.

Here’s a video dedicated to Graham I stumbled across a few years ago that’s worth a watch:

Here’s what I wrote about David Swensen in Organizational Alpha:

I’ve spent my entire career managing institutional portfolios so I’m often asked for recommendations on the best books to read on the subject. There’s really only one. Without question that book is Pioneering Portfolio Management: An Unconventional Approach to Institutional Investment by Yale’s David Swensen. This is the bible for many institutional investors; but that’s really it, as far it goes for books, in this space.

While Swensen’s book is certainly chock full of useful advice on how to run a successful investment program, many readers have probably taken away the wrong message after reading it; namely, that they can match Swensen’s success and imitate his spectacular results.

Over the past three decades, the Yale Endowment has grown at a rate of roughly 14 percent per year. The fund now has around $26 billion under management. In that time, they’ve outperformed the average college endowment fund by 5 percent per year.

Charley Ellis wrote, “David Swensen has done more to strengthen our educational and cultural institutions than anyone else on our planet — and he’s still developing and sharing his best thinking with everyone in a genial and inspiring illumination of how much good one very fine man can do.”

See 6 Reasons For David Swensen’s Success at Yale for more.

It’s been reported that George Soros returned 32% annually over a 26-year period with his Quantum Fund. It also helps he has some good stories that ad to his legend as an all-time great. In an early profile of the macro hedge fund manager in the 1980s, a rival fund manager proclaimed, “We’re playing tennis and he’s playing something else.”

Soros famously claimed his back pain1 could tell him when to get out of a bad position (per the book More Money Than God):

If there was trouble stirring in his portfolio, Soros would first know about it when his back seized up; believing that markets could turn against him at any time, Soros would defer to these physical signals and sell out his positions. The business of investing consumed all the time and energy he had. He thought of himself as a boxer in training who had to sacrifice all personal life for the sake of victory. He compared himself to a sick person with a parasitic fund swelling inexorably inside his body.

Going head-to-head with the Bank of England in the 1990s and coming out on top with a $1 billion profit cemented the legend of Soros.

Anyone we missed?

Further Reading:

You Are Not Stanley Druckenmiller

Would Keynes Have Been Fired as a Money Manager Today?

1The Irish Times profiled Soros a number of years ago and his son gave a funny answer about these signals:

According to his son, Robert, Soros’s trading was always influenced by more than reflexivity. “My father will sit down and give you theories to explain why he does this or that”, he once said, “but I remember seeing it as a kid and thinking, ‘Jesus Christ, at least half of this is bullshit’.

“I mean, you know [that] the reason he changes his position on the market or whatever is because his back starts killing him. It has nothing to do with reason. He literally goes into a spasm and it’s this early warning sign.”

Soros has admitted to relying greatly on “animal instincts”, saying the onset of acute pain was often “a signal that there was something wrong in my portfolio”.

His decisions, then, “are really made using a combination of theory and instinct”.