The United States is the envy of the world in terms of financial markets and economic performance.

Ruchir Sharma at The Financial Times outlines how this is impacting capital flows:

Global investors are committing more capital to a single country than ever before in modern history.

And the dollar, by some measures, trades at a higher value than at any time since the developed world abandoned fixed exchange rates 50 years ago.

The US now attracts more than 70 per cent of the flows into the $13tn global market for private investments, which include equity and credit.

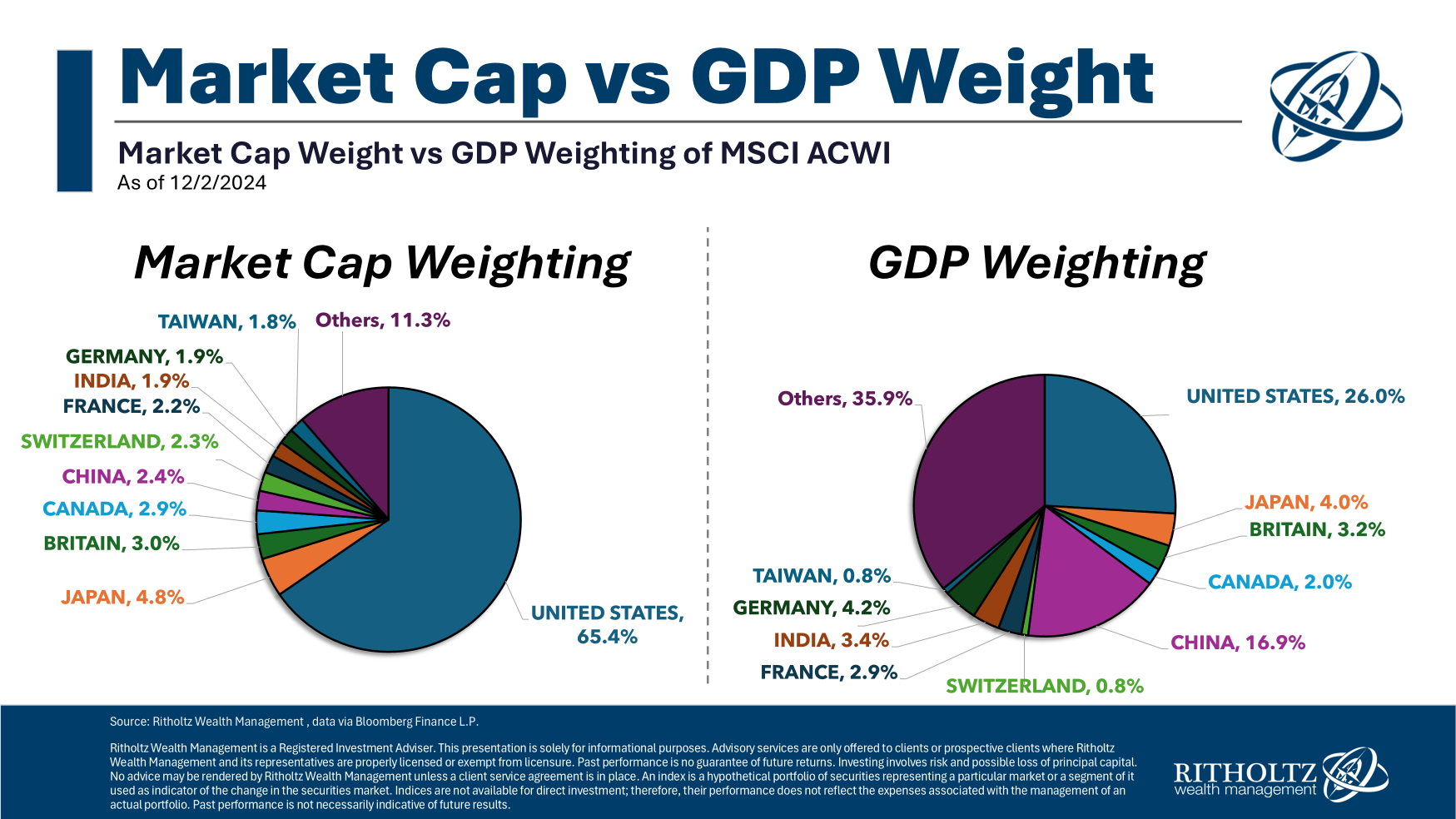

America’s share of global stock markets is far greater than its 27 per cent share of the global economy.

There are reasons for the tidal wave of money pouring into the United States.

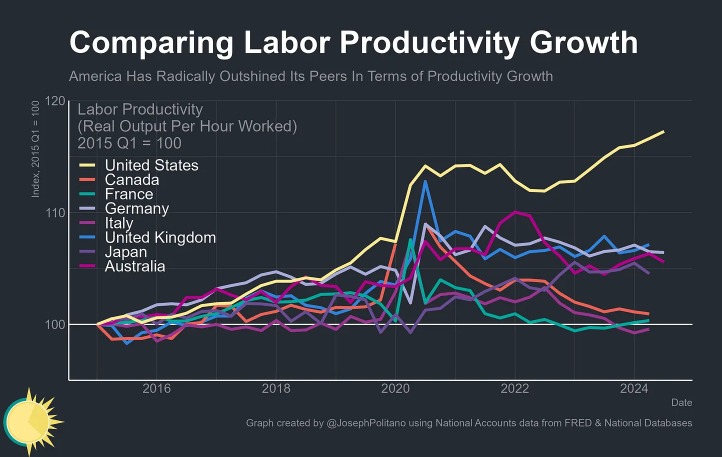

Joey Politano breaks down the productivity boom in the U.S. and how it compares to the rest of the developed world:

He explains:

Productivity growth is nothing short of the bedrock of progress–in the long run, creating more with the same amount of labor is the only way to durably increase wages, consumption, and society’s overall prosperity. That makes it such a historic achievement that American economic output per hour worked has risen 8.9% over the last five years–faster than the five years prior or any point in the 2010s–in spite of the COVID-19 pandemic.

We’re on an economic heater at the moment.

You can’t offer a single variable as a reason when dealing with the complexities of something as large as the global economy. But one of the main reasons for our success boils down to being more comfortable taking risk.

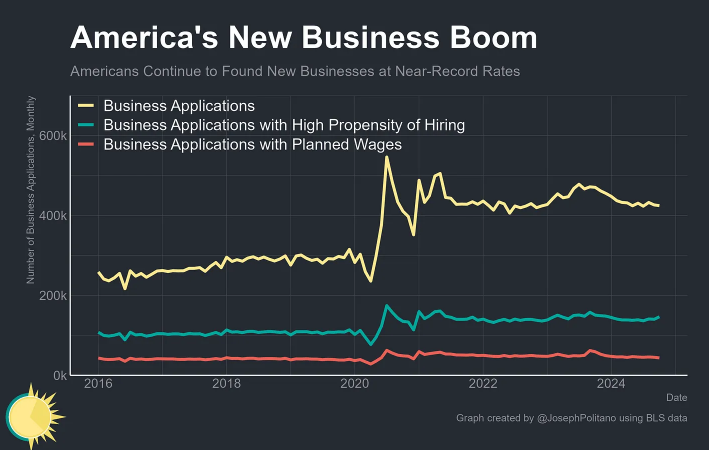

Just look at all of the new businesses that have been formed since the pandemic:

Risk-taking is part of our culture just like spending money, investing in stocks and gambling.

The stock market is not the economy but it is pretty wild that the United States makes up around a quarter of global economic output but nearly 70% of the worldwide stock market:

You’ll notice most other countries have relatively similar weightings for stocks and GDP — Canada, Japan, Britain, France, Germany, etc. The two outliers here are China and the United States.

China makes up 17% of world GDP but less than 3% of the MSCI All-Country World Index. These numbers aren’t static of course.

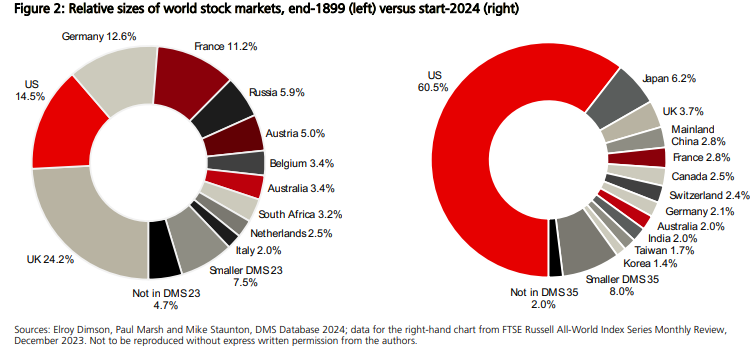

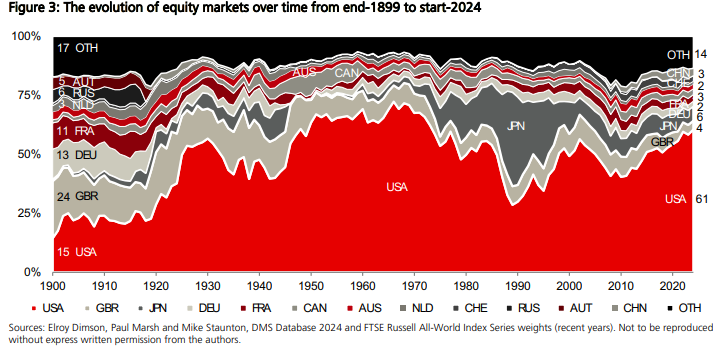

UBS Global Investment Returns Yearbook annually updates one of my favorite charts that shows the differences in country weights between 1900 and now:

The United States was less than 15% of global equity markets in 1900. Now it looks like we’re slowly swallowing the rest of the world.

These moves don’t occur in a straight line though:

In the 1950s and 1960s, the U.S. had an even higher share of world equity markets. Japan nearly caught up to us by 1990 but that reversed just as quickly. The U.S. shot up again in the 1990s but fell in the first decade of this century. Now it’s back on the upswing.

I’m not all that concerned with the current weightings. These things are cyclical but the cycles tend to play out over multi-decade timeframes.

My biggest question for the future is this: Can anyone challenge the United States in terms of economic might?

It sure doesn’t seem like it in the current environment.

Further Reading:

The New Normal of Negativity