By the end of the 1970s inflation was out of control.

The New York Times wrote a front-page story where they interviewed a bunch of normal people to see how inflation was impacting their lives.

By that point CPI was up a cumulative 73% in the decade or nearly 7% per year. Inflation had been raging on long enough that it was finally starting to impact people’s habits:

In interviews across the country, The New York Times found that the “throwaway society” of the late 1960’s and early 1970’s is being replaced, in many cases, by a new ethic of economy. People are driving cars longer and wearing clothes more often, planting their own gardens and fixing their own plumbing.

Many Americans use the same words to describe this new attitude: “We buy only what we need, not what we want.” But this means that some of the juice of life, from new stereos to trips to the beach, is getting squeezed dry by the pressure of rising prices.

One of those interviews was with a bread salesman named Terry McLamb from Raliegh, North Carolina. McLamb said he, “feels powerless to improve his living conditions.” Here’s what they wrote at the time:

But many others are left with feelings of frustration and fear. Terry McLamb, the bread salesman, has seen his income rise from $9,000 to $15,000 a year in five years, but says: “I was getting along better on the lower income. It’s all got to come to a point somewhere, but I don’t know where.”

In the five years ending 1978, the consumer price index was up 47%. McLamb’s income rose 67% in that same period. His income outstripped inflation by 20% yet he was miserable.

Obviously, inflation isn’t the only variable that can impact how someone feels about their financial prospects at any given moment. But inflation can play head games with you, especially when it happens in big chunks.

Most people believe they deserve the higher wages that tend to accompany higher inflation. No one feels like they deserve higher prices. Plus, people get used to higher wages quicker than higher prices because you see the prices every time you spend money.

It’s been over 40 years since we’ve dealt with sky-high inflation, so it makes sense that people are thrown off by the price increases we’ve experienced these past few years.

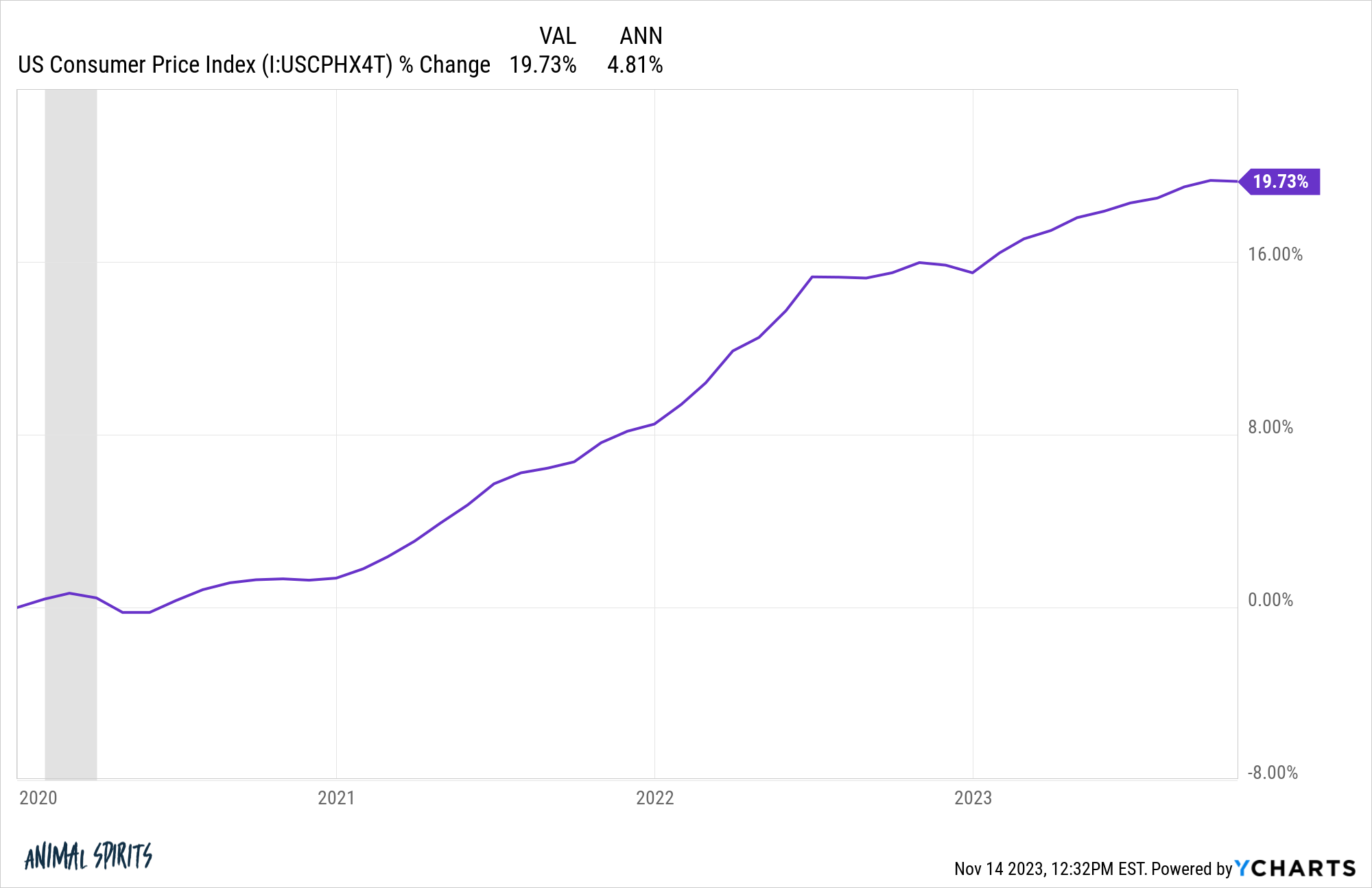

Cumulatively, U.S. CPI is up nearly 20% since the start of the pandemic:

The pace of inflation has slowed but those higher prices are now baked in.

Fed Governor Lisa Cook recently stated in a speech she thinks most people want prices back to pre-pandemic levels:

“Most Americans are not just looking for disinflation. You and I as macroeconomists are looking for disinflation. They’re looking for deflation. They want these prices to be back where they were before the pandemic,” Cook said.

“That’s my own theory,” she concluded. “But I hear that a lot. I don’t have to wait for articles about that, I hear that from my family, from lots of different people.”

I get it.

People don’t enjoy economic volatility.

But that’s not how this works. That’s not how any of this works. You don’t get to keep your higher wages while prices revert back to 2019 levels. Deflation might sound appealing regarding prices, but that also means lower wages, lower economic growth, and job loss.

Inflation isn’t a good thing, per se, but it is the lesser of two evils.

One person’s spending is another person’s income. Higher wages come from higher prices or vice versa.

As long as the economy is growing, deflation is rare.

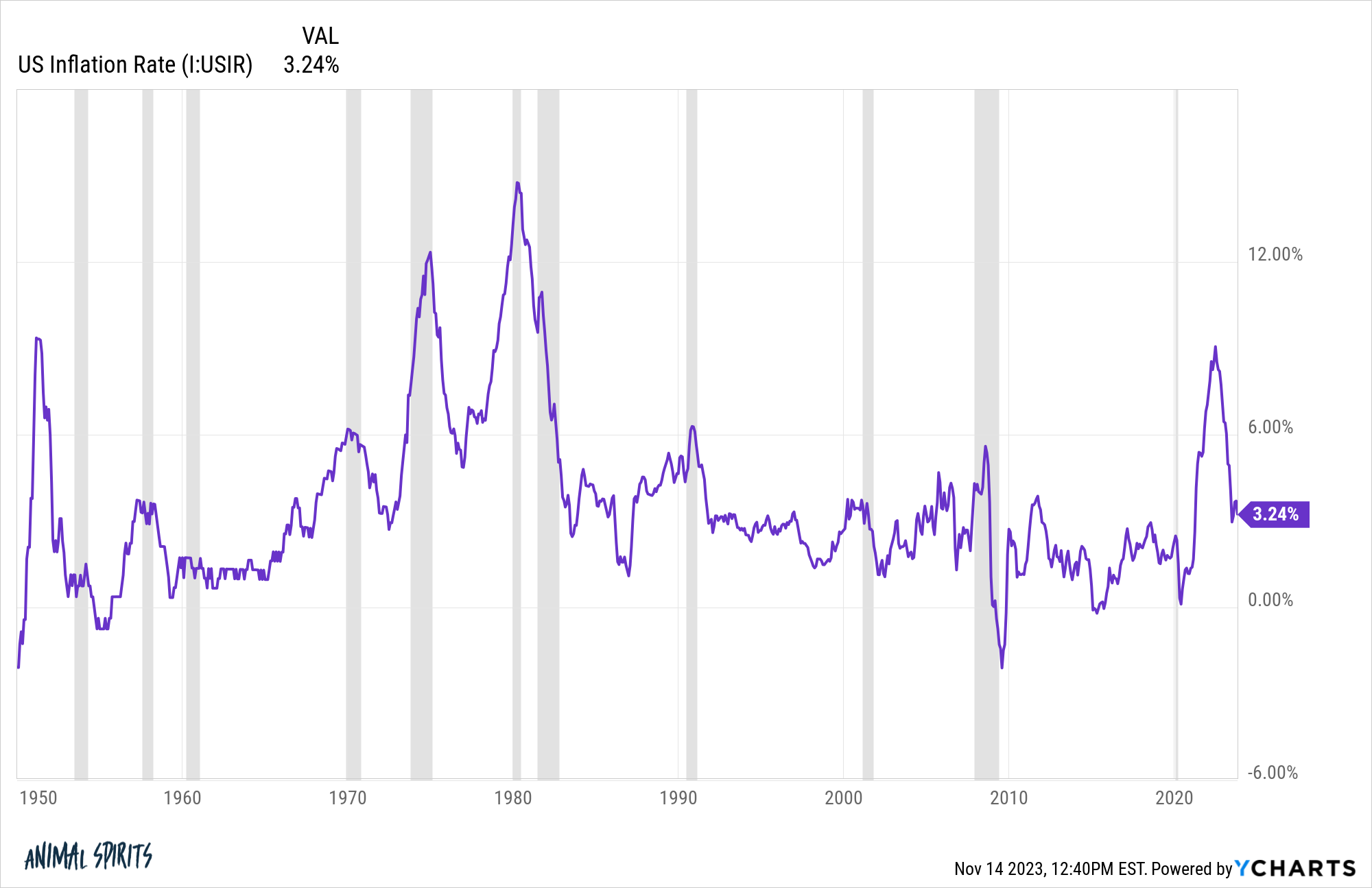

This is the annualized inflation rate in the U.S. going back to 1950:

Out of the nearly 900 monthly inflation readings in this time frame there have been just 33 monthly deflationary numbers. So prices have declined less than 4% of the time since 1950.

Deflation occurred in the 1950s coming down from the post-WWII sugar high, during the Great Financial Crisis and briefly in 2015. That’s it. The rest of the time, prices rose.

Look at what happened following the 1970s inflationary spike. We never had deflation. Prices never fell in the 1980s or 1990s. They kept moving up, just at a slower pace.

The biggest difference between now and the 1970s is that people began changing their habits back then. That doesn’t seem to be the case for the American consumer yet.

Matthew Klein wrote about our current spending habits at The Overshoot recently:

Spending on U.S.-made goods and services rose at a blistering 9% yearly rate in 2023Q3. Even after subtracting inflation, real production rose at a 5% yearly rate. Some of that exceptional performance was likely a fluke, and should be discounted accordingly. But even before the most recent blowout quarter, total spending has consistently been growing at a yearly rate of a little over 6% since the middle of last summer. Moreover, inflation-adjusted spending by Americans–U.S. GDP excluding the impact of changes in inventories and the trade balance–has consistently been growing slightly faster than 3% a year in 2023Q1-Q3. By comparison, real domestic demand was rising just 0.8% a year on average in 2022Q1-Q4, even as total nominal spending and incomes were rising about 7% a year.

In other words, while there has been a significant deceleration in the rate of price increases from around 6% a year to 3% a year, the growth rate of the dollar value of spending and incomes has slowed by much less (from 7% a year to 6% a year). So far, this has translated into a massive acceleration in the growth rate of Americans’ living standards.

This is probably one of the biggest reasons Americans are so annoyed with higher prices — they keep right on paying them.

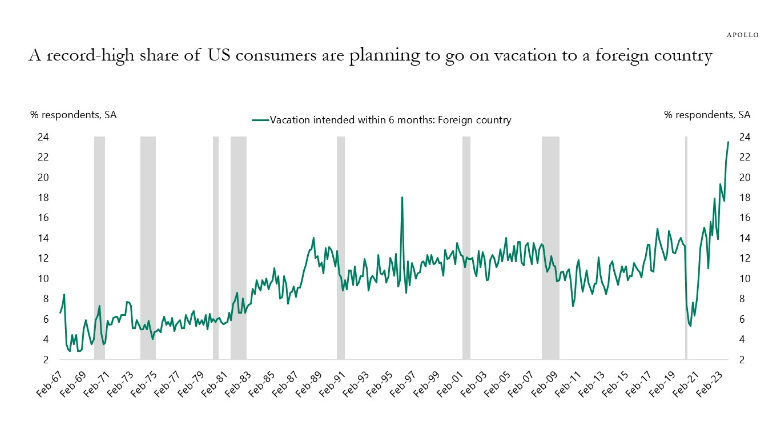

Torsten Slok at Apollo highlighted a survey this week that shows a record number of consumers plan on vacationing to a foreign country within the next 6 months:

Cruise bookings are running at a rate that’s 25-30% higher than pre-pandemic levels. Cruise ships are running out of inventory.

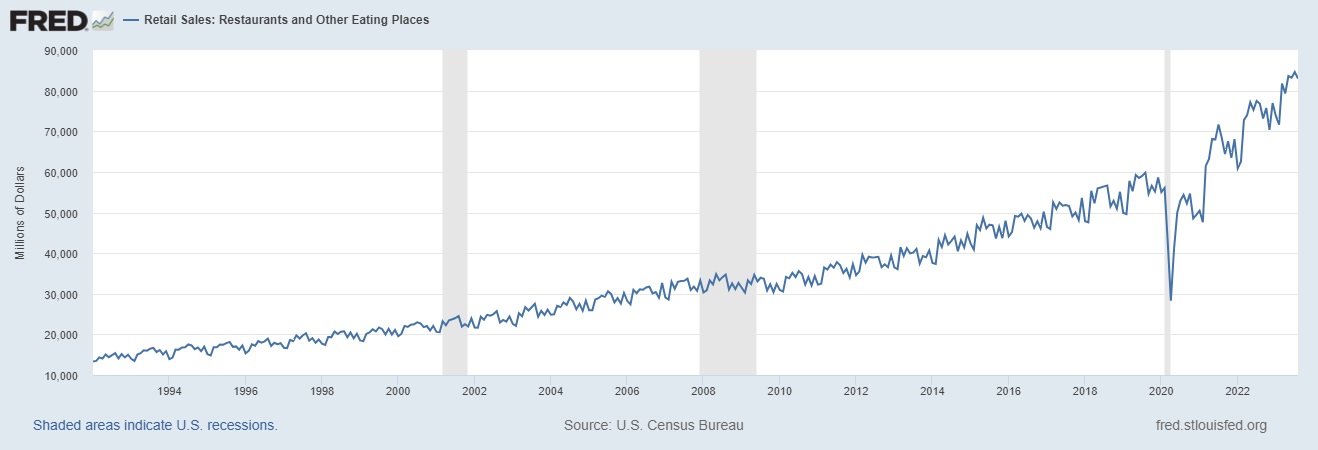

Look at the sales numbers for restaurant spending in America:

It’s way higher than the pre-pandemic trend.

The best-selling vehicles in America in 2022 were the Ford F-150, Chevy Silverado and Dodge Ram.

People are still spending $50-60k on new trucks, going out to eat, taking cruises and going on European vacations.1

This is not everyone and there are certainly instances where people are cutting back. But collectively, the biggest impact inflation has had on consumer habits is we all complain more than we used to. Maybe that’s because everyone is spending more too.

Luckily, the rate of inflation is slowing. We’ll see if our rate of spending catches up eventually.

Further Reading:

Complacency in the U.S. Economy

1This might be a get off my lawn moment for me but I feel like no one I knew ever traveled to Europe when I was growing up. Now, it’s commonplace to hear about European vacations.