“Everything in life is founded on confidence.” – Ivar Kreuger

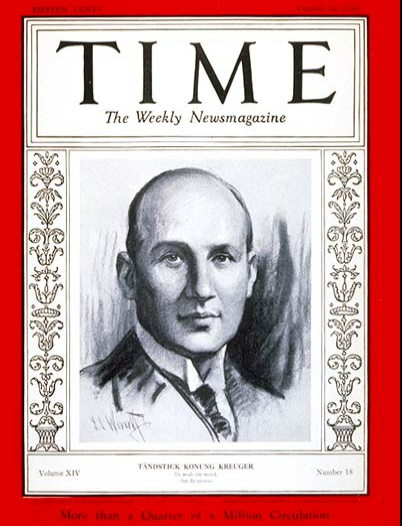

On October 28, 1929, Swedish businessman Ivar Kreuger appeared on the cover of Time Magazine.

He was one of the most talked about people in the United States at the time because he was rich, powerful and mysterious. Kreuger controlled three-quarters of the production and sales of matches, owning more than 200 match factories in 35 different countries all around the globe.1

The Match King, as he was called, owned a private island in the North Sea and apartments all over the world. He was friends with actress Greta Garbo and an advisor to President Herbert Hoover. Kreuger played a prominent role in the Nobel Prize ceremonies and had business dealings with world leaders and prime ministers.

The man was treated like a celebrity.

There were even plans to use his story to depict the American dream in a full feature-length film. That movie never saw the light of day because he shot and killed himself shortly thereafter as his empire of fraud came crumbling down in the Great Depression.

Before it all came to an end, he created one of the biggest business empires in the world.

Kreuger’s take-no-prisoners approach to business quickly allowed him to turn his match company, International Match Corporation, into a monopoly in the space.

Many countries were cash-strapped from their World War I debts. So Kreuger’s strategy for world domination of the match industry was to loan money to needy countries at favorable terms so government officials would allow him to buy up the match companies and factories within their borders.

The problem is International Match was only getting 6-8% in interest on those loans while Kreuger’s financial holding company was paying out double-digit dividends to investors, upwards of 15-30% in some cases.

It doesn’t take a genius to understand that spread does not make for a sustainable business model. But Kreuger was a master at deception when it came to the financials of his various holding companies.

He was the only one who knew what the actual profit and loss numbers looked like for International Match and all his various financial holding companies. In fact, Kreuger created some four hundred different off-the-book conduits to move money around and hide what was really going on.

He was so good at hiding what was really going on that his board and investors had no clue what was really going on. In fact, they had total faith in the Match King because he was so well-connected politically.

Percy Rockefeller, the nephew of John Rockefeller, was a member of the board of directors. Rockefeller gushed to other board members, “He [Kreuger] is on the most intimate terms with the heads of European Governments. Gentlemen, we are fortunate indeed to be associated with Ivar Kreuger.”

Little did Rockefeller know that Kreuger faked calls to prime ministers and presidents to prove how powerful he was.

He had some relationships but not nearly as many as his board thought.

Kreuger’s match business was on the way out as a profitable business once electricity became more ubiquitous but the stock market was on its way in as all sorts of new and exciting financial products were created during the roaring 20s.

Kreuger wanted to prove he belonged with the elites of the world and what better proving ground than the greatest wealth machine ever created?

He truly believed all of his lies and fraudulent activities would reverse someday if he could only hold things together for a little longer. And he almost did it too, if it wasn’t for the greatest crash the world had ever seen.

The tide has never gone out as much as it did during the Great Depression and it revealed there were a massive amount of people who forgot to wear their swim trunks.

By early 1929 investments in Kreuger & Toll, his financial holding company, were the most widely distributed securities in the world. Investor demand was so high these securities were selling at an unbelievable 730% premium to par value.

Which worked until it didn’t, when the floor fell out from underneath the market and stocks cratered in the fall of 1929 as the roaring 20s came to a screeching halt without warning.

Time Magazine immediately regretted its decision to put Kreuger on the cover. They quickly changed their tune by running a follow-up story which brought up doubts about his scheme and the company’s ability to continue to pay such lofty dividends.

Investors didn’t care just yet but they would soon enough.

Kreuger worried investors would abandon ship so he raised the dividend yield to 30% and prayed the downturn would end in short order.

It didn’t.

From June 1931 until December of that same year, his securities fell in value by as much as 80%.

Not only was business slowing during one of the worst economic downturns of all-time, but Kreuger had margined up the securities for his businesses to an unimaginable level, often faking the collateral to do so.

When the house of cards finally came crashing down, Krueger shot and killed himself on March 12, 1932.

An audit after the fact revealed his companies were bankrupt. Claims against his estate were more than $1 billion.

After he took his own life, few people realized the size and scale of the fraud Kreuger had pulled off. This was one of the most well-known, wealthiest, and respected businessmen in the world.

Why would he do such a thing?

Many frauds start out as a legitimate business or idea that simply gets taken too far through some combination of greed, loose morals, and overconfidence. Once the ball gets rolling, money begins pouring in, and a certain amount of power is obtained it becomes difficult to stop the train.

People will do just about anything they can to ensure the money and power continue indefinitely.

The 1920s were a breeding ground for financial fraud and malfeasance but Kreuger wasn’t running a Ponzi Scheme in the traditional sense.

If anything the scale of his operation was much larger and lasted much longer than Charle Ponzi’s. Kreuger raised fifty times as much money and his business dealings lasted ten times as long.

It was running legitimate businesses, at least when he started out. When that didn’t last he went off the deep end.

The problem is he wasn’t allocating capital very well and made promises he couldn’t possibly hope to keep because each of his enterprises was so heavily indebted.

Plus, the Match King had complete control over the funds in his collection of businesses and did what he pleased with that money.

Kreuger kept the books for his vast enterprise but chose not to share that information with the investors or any of his employees. The books were fudged in both good and bad years to balance things out so no one would notice. His belief was he just needed profits to grow enough to be able to continue paying high dividends to pay off the debts.

But when your burn rate exceeds your revenue by a factor of almost five-to-one, eventually you’re going to go broke.

To keep the auditors at bay he would simply tell them his deals with governments were politically sensitive and couldn’t be disclosed.

A year after congress called him “the greatest swindler in all history,” the SEC was created. He wasn’t the sole reason for greater consumer protection but definitely played a role.

One of the hardest things to do as a human being is to keep your wits about you when everyone else is seemingly going mad.

This is especially true when there’s an enigmatic figurehead overseeing the operation.

A well-known British writer at the time called Kreuger, “The best-liked crook that ever lived.”

One of his closest colleagues said, “There was an odd air of greatness about Ivar. I think he could get people to do anything. They fell for him, they couldn’t resist his peculiar charm and magnetism.”

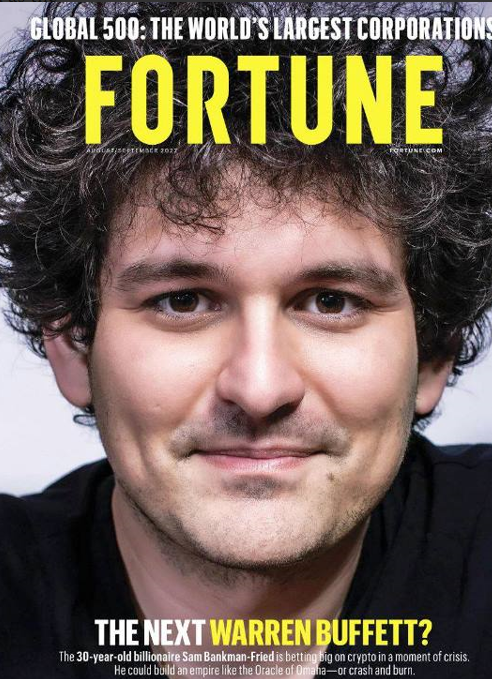

Which brings us to Sam Bankman Fried.

He too had a glowing cover story just before going bust in spectacular fashion.

The boy wonder of crypto may have just experienced the fastest destruction of wealth in history.

The founder of crypto exchange FTX went from being worth $16 billion to being worth $0 (probably less than $0) in the span of a day.

According to the Wall Street Journal, FTX had $16 billion in customer assets but lent out more than half of those assets to his crypto trading arm, Alameda.

Everyone is still trying to figure out what the hell happened but it appears he was using customer deposits to cover losses in his hedge fund along with a bunch of other nefarious actions.

Not great.

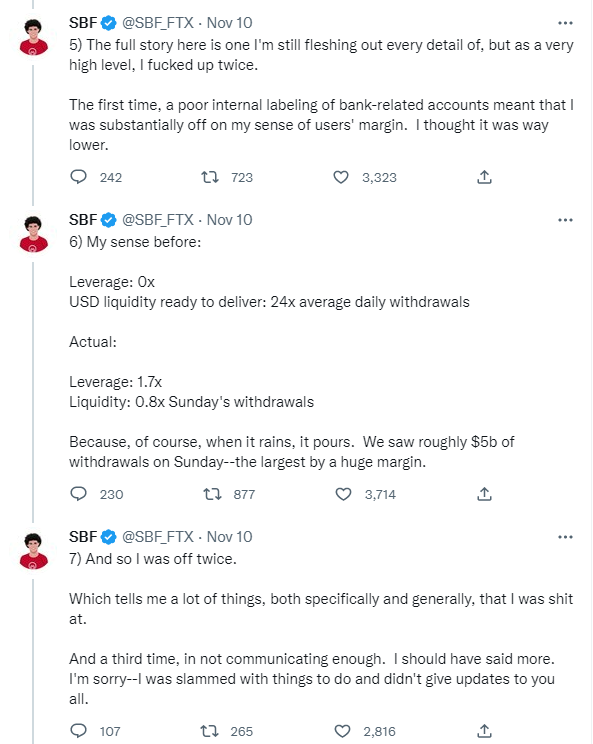

Much like the Match King, SBF seemed to have total control over the books at FTX:

I can’t believe he admitted this.

Don’t pass Go, straight to jail.

It’s estimated FTX had more than 130 affiliate companies spread across the globe.

I guess he was basically keeping track of margin accounts in his head? On the back of a napkin? I can’t tell if he’s telling the truth here or not but there was obviously a lack of internal controls at FTX.

FTX seems to have started out as a legitimate crypto exchange. And when losses started piling up at his trading arm the misallocation of resources went to ludicrous speed.

This is a classic example of too much, too soon.

Too much money. Too much control. Too much leverage. Too much attention. Too much power. Too much everything.

The way I see it, there are two types of charlatans.

Type I charlatans are the visionaries who are more or less sincere but wind up ruining their followers anyway because they take their ideas to the extreme or fail to account for the unintended consequences of their actions.

These false-positive charlatans are so passionate that it becomes difficult for their victims to see any downside. When you combine intellect, passion, and people in search of money and/or power, it’s easy to become blinded by the potential risks.

Once a Type I charlatan gets a taste of success, it’s tough to pull in the reins when things go wrong.

Type II charlatans are the out-and-out fraudsters who blatantly set out to take people for all they’re worth. These hucksters are only interested in making as much money as possible and don’t care who gets hurt in the process.

These charlatans are false negatives because they lie to persuade you to part with your money. It’s difficult to see through this type of charlatan because they know exactly how to sell you. They understand human behavior and tell you exactly what you want to hear.

The strange thing about both Kreuger and Bankman-Fried is it seems they each started out as Type I charlatans and ended up Type II once they got in too deep.

When technology moves forward by leaps and bounds, as it did in the first part of the 20th century, people prefer betting on the future more than betting on the past.

It appears the same thing happened with crypto.

For Krueger, the past was selling matches while the future was selling financial securities. No one really knows why but something shifted in his business strategy once greed became the currency of the 1920s.

It appears the same thing happened to Sam Bankman-Fried.

The more things change the more they stay the same.

Enigmatic charlatans are as old as time.

Further Reading:

Type I & Type II Charlatans

The Golden Age of Fraud is Upon Us

1Matches were used in a variety of ways before everyone had electricity — to light kerosene lamps, gas heaters, candles for light, fires for warmth, stoves for cooking, and for everyone’s favorite deadly habit back then — smoking. Cigarette production in the U.S. doubled in the 1920s so matches were used for both needs and desires.

The Kreuger details are adapted from my book, Don’t Fall For It: A Short History of Financial Scams. It feels as though I could write an entire new volume base exclusively on the past 3 years.