Pockets of the market are flirting with silly territory.

SPACs, IPOs, and electric vehicle companies are all sprouting up like weeds.

I’m not intelligent enough to sort through the winners and losers in these areas but the fact that there are currently winners means there will be a flood of losers to follow. That’s how these things work. When speculative investments are in demand, the supply ramps up to meet it.

And many of those losers will be pushed relentlessly by hucksters and charlatans who flock to rising markets like me to a new Tom Cruise movie.

Charlatans tend to flourish when some or all of the following characteristics are present:

- When there’s an “expert” with a good story

- When greed is abundant

- When capital becomes blind to risk

- When individuals begin taking their cues from the crowd

- When markets are rocking

- When innovation runs rampant

There are two types of charlatans you need to watch out for when trying to avoid getting taken advantage of during these types of market environments.

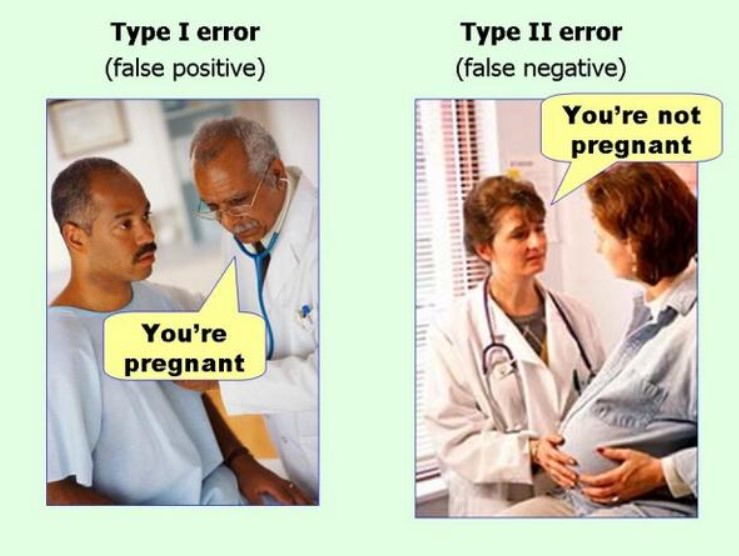

When testing a hypothesis using statistics, there are two types of errors a statistician can make. A type I error is when you reject a null hypothesis that is actually true. A type II error is when you accept a null hypothesis that is actually false.

This meme is the best explanation of this concept I seen:

Type I charlatans are the visionaries who are more or less sincere but wind up ruining their investors anyway because they take their ideas to the extreme or fail to account for the unintended consequences of their ideas.

These false-positive charlatans are so passionate that it becomes difficult for their victims to see any downside. When you combine intellect, passion, and people in search of money and/or power, it’s easy to become blinded to potential risks.

And once a Type I charlatan gets a taste of success, it’s tough to pull in the reins when things go wrong.

Type II charlatans are the out and out fraudsters who blatantly set out to take people for all they’re worth. These hucksters are only interested in making as much money as possible and don’t care who gets hurt in the process.

These charlatans are false negatives because they lie to persuade you to part with your money. It’s difficult to see through this type of charlatan because they know exactly how to sell you. They understand human behavior and tell you exactly what you want to hear.

They move the goalposts and shift the blame when it appears they’re wrong and understand how to massage your ego to keep you in line.

Bernie Madoff is a type II.

Elizabeth Holmes likely started out as a type I and slowly morphed into a type II once she realized Theranos was never actually going to happen.

My favorite example of the two types of charlatans comes from perhaps the biggest double-bubble in history which occurred in the 18th century with the Mississippi and South Sea companies.

A Scotsman named John Law was basically the Magellan of the modern monetary system and France was his test case for a relatively new paper currency system.

France was on the verge of financial ruin from a combination of excessive debt levels from multiple wars and a corrupt King who spent far too lavishly.

To dig them out of this debt burden, Law proposed a shift from hard currencies such as gold and silver to paper currency. Paper money was rare at the time so to get buy-in from citizens Law set up a system to back that cash with government debt which could be converted into equity shares of a new exploration company.

That exploration venture, the Mississippi Company, was supposed to explore the Louisiana Territory and strike it rich by finding more gold and other precious metals (bringing the whole thing full circle).

The problem is the company never lived up to its hype and more or less didn’t do what it was supposed to do. Investors didn’t really care because share prices were rising based purely on speculation of what the company could become.

Unfortunately, this debt for equity swap was more advantageous for the French government than its citizens. Speculation ran rampant, shares went parabolic and eventually crashed as bubbles are wont to do.

Today’s equivalent would be convincing holders of U.S. treasuries to convert their bonds into shares of Nikola to help the U.S. government pay off its debts…and then lopping on some margin to buy those shares for good measure.

Law is a prototypical type I charlatan. He had complete faith in the system he was creating, going so far as reinvesting his own money into the scheme.

John Law was a visionary who was sincere but wound up ruining investors anyway, failing to take into account real-world dynamics or consider how his ideas could go horribly wrong. Encouraging investors to use borrowed money to buy shares of a fraudulent company didn’t help matters.

Great Britain took notice of the overnight riches being created in the Mississippi Company (pre-crash) and the Brits did not like seeing their neighbors and seldom enemies getting wealthy.

Enter the personification of the type II charlatan, John Blunt. Blunt had one aim in life – to become fabulously wealthy by any means necessary. And not only did he want to become rich, he wanted to become rich as fast as humanly possible.

It just so happens a bubble is the perfect environment to make this happen.

Unlike Law, Blunt’s plan had no intellectual underpinnings. He made up for a lack of book smarts through a combination of self-confidence, charisma and an ability to sell. Blunt saw an opportunity to use the government, the public, and the South Sea Company to his advantage to both create the illusion the government could erase their debts and enrich himself in the process.

The South Sea Company was set up as a similar exploration scheme to the Mississippi Company to relieve England of their excessive war-time debts.

The biggest difference is Blunt essentially ran it as a pump-and-dump, spreading false rumors, bribing the courts, allocating shares to friends and family, pushing “investors” to utilize margin and forcing a lack of oversight as a director to the company.

The South Sea Company likely ushered in the word “bubble” to the lexicon as it pertains to financial markets because so many copycats popped up to soak up the speculative demand it created.

It flamed out just like its predecessor but not before investors collectively lost their minds in the process.

Blunt and Law were both shunned and more or less died penniless in lives of exile following the failure of their respective schemes.1

I’m not calling for a repeat of this bubble (yet) but the combination of extremely low interest rates and a speculative fever all but guarantees the presence of charlatans to make promises of easy riches in the current environment.

Types I charlatans are harder to spot because they actually believe in what they’re selling whereas type II charlatans just tell you what you want to hear.

The antidote to either type I or type II is a healthy dose of common sense and the understanding that there is no such thing as easy money or overnight riches.

People can and will make money in speculative investments today.

Just be careful because the higher these investments go the more likely it is certain investors will get taken for a ride.

This piece was adapted from Don’t Fall For It: A Short History of Financial Scams.

1If they were around today they would likely get another shot running a hedge fund or venture operation.