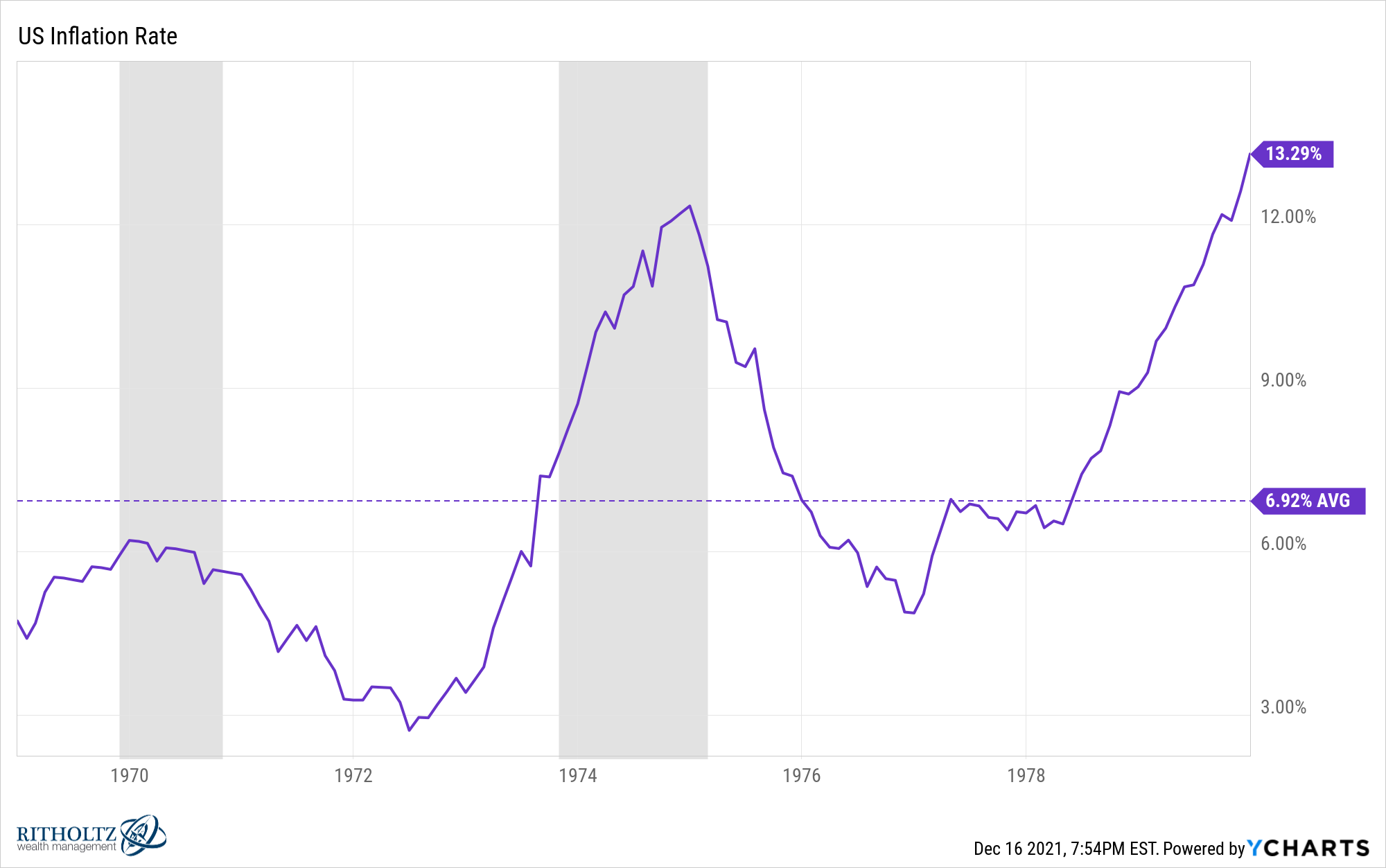

By the time Paul Volcker raised interest rates enough to throw the United States into a recession in 1980, the inflation rate had averaged 6.9% for the previous 11 years.

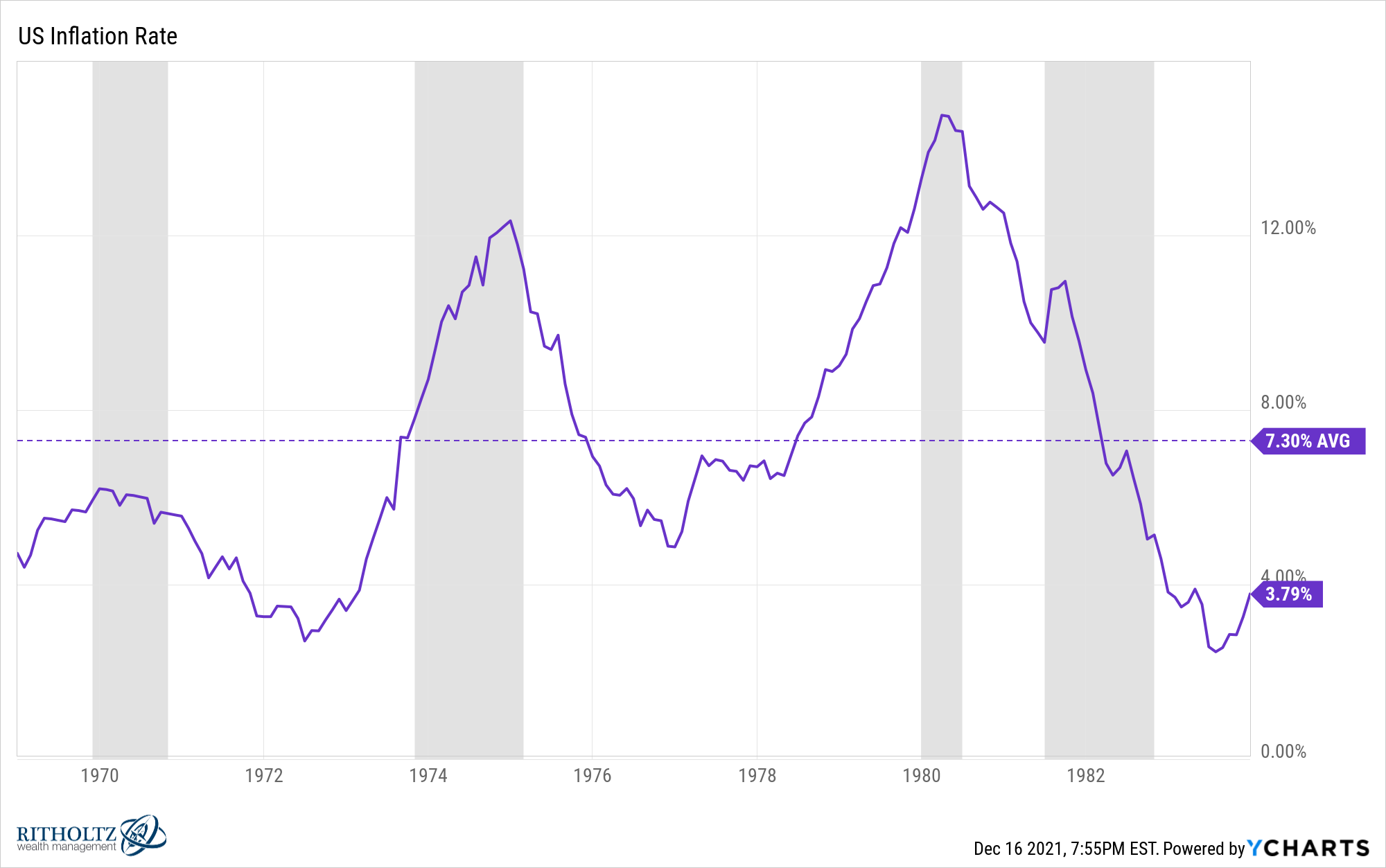

It would take another recession just a year later to finally slay the beast that was persistently high inflation:

Volcker is seen as a hero today but at the time he was public enemy number one. By the end of 1982, the unemployment rate was close to 11%.

The annualized inflation rate first went above the long-term average of around 3% in April of this year, meaning we’ve been running a little hot on prices for about 8 months now.

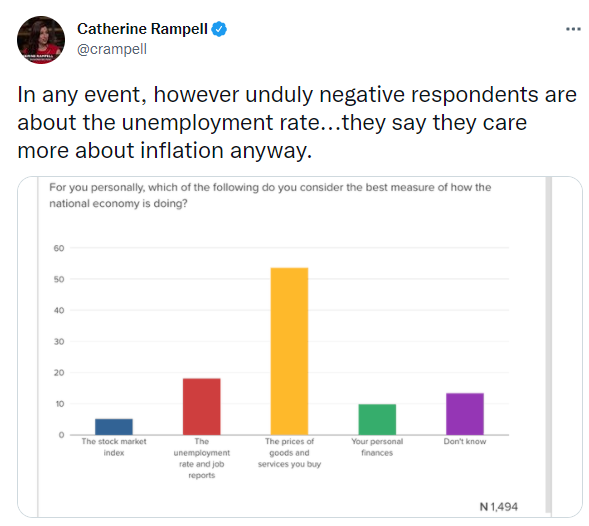

I can’t imagine what it was like to live through the 1970s because 8 months of this and people are already fed up:

There is some serious recency bias in this kind of survey because there is no way people would have answered this in the previous 3 decades or so. People only worry about inflation when it’s here.

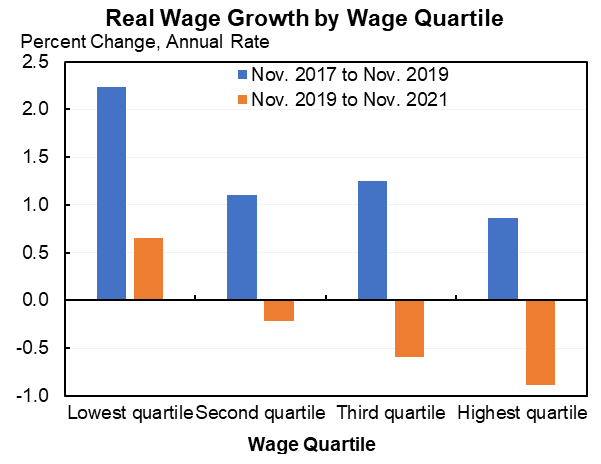

Of course, people dislike inflation for good reason:

Not only are we all paying more at the gas pump and grocery store, but wages are falling on a real basis for everyone except those in the lowest quartile of the income scale. If this persists, people are not going to be happy.

It certainly feels like it’s time for the Fed to normalize monetary policy (if there is such a thing as normal in the economy). If we can’t handle 3 or 4 rate hikes with inflation and economic growth running hot, a shortage of workers and generationally low interest rates, when can we?

The problem is it’s not like taking interest rates from 0% to 0.75% or 1% is all of the sudden going to fix the supply chain issues. The Fed can’t make more semiconductors. They can’t unpack container ships at the LA ports. They can’t create more houses out of thin air.

The Fed kept rates at 0% from the end of 2008 all the way through 2015 and we didn’t even come close to sniffing high inflation. In fact, from 2009-2020, the average inflation rate in the U.S. was just 1.5% per year.

The big change this time around was a combination of the pandemic and massive fiscal policy. Those two factors are having a far greater impact than the Fed “printing” money.

Sure, the Fed can’t fix the supply chain problems but they can dampen the demand side of the equation. That’s basically what Volcker did by raising rates to double-digit levels.

This is why there is a growing chorus of financial pundits who would like the Fed to raise rates high enough to cut off demand and perhaps throw us back into a recession.

Call me crazy but I would rather avoid a recession if possible and find some middle ground between Volcker and Powell.

The government has done a terrible job with both its policies and messaging behind inflation.

The messaging part should be easy. The government spent so much money and handed out so many checks because the alternative was 25% unemployment rates for months on end. We stopped a depression in its tracks.

The fiscal damage to households and municipalities would have been far greater than the current inflationary environment.

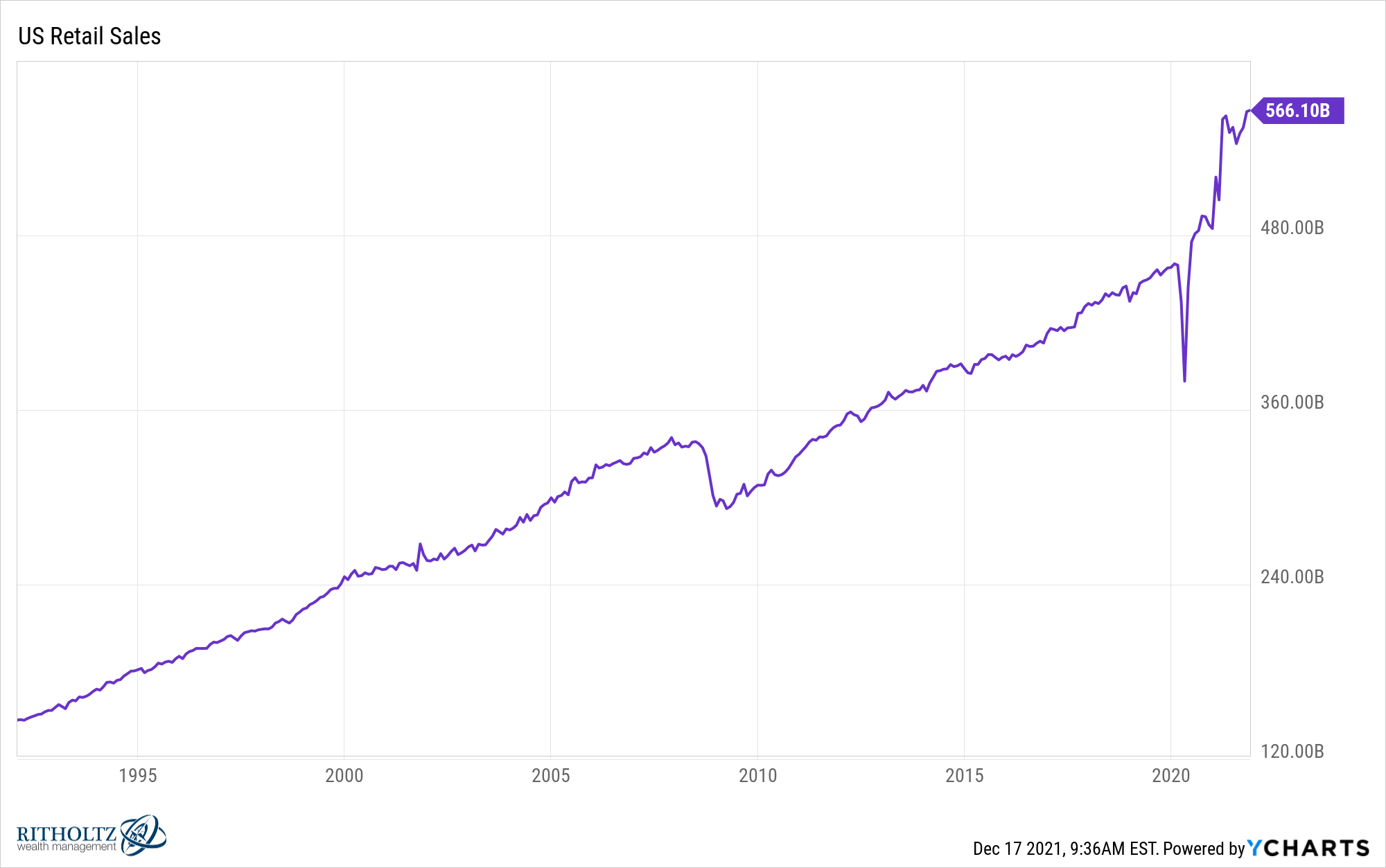

The good news for the demand side of the equation is this can’t last forever:

There are no more stimulus checks coming. Yes, the pandemic is still here but there is no way the politicians are signing off on more money to households with inflation where it is.

The message should be “we don’t want to kill off strong demand in the economy but we’re going to do whatever we can to make things easier on you until we can get the supply constraints figured out.”

How about the tariffs the Trump administration enacted? Why don’t we lift those or at the very least put them on hiatus for 12 months? Wouldn’t that immediately lead to lower prices for many products and input costs?

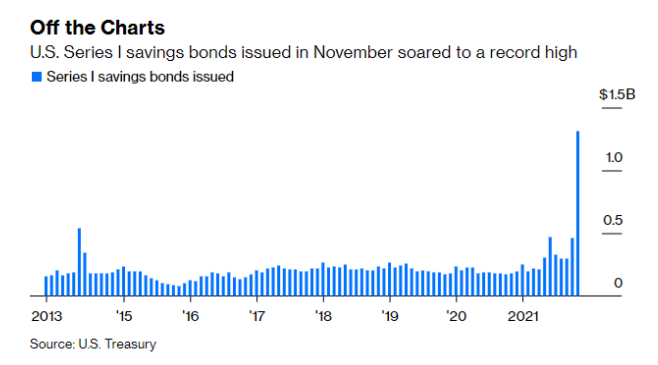

Savers outside of the stock market are also experiencing a double-whammy of low rates at a time of high inflation, leaving real yields squarely in negative territory. During inflationary spikes in the past, at least people could bank on higher nominal yields.

Just look at the demand for Series I savings bonds which have yields that are indexed to inflation:

These bonds are currently paying more than 7% annualized yields until rates reset (which happens every 6 months). The problem is each individual is capped out at a maximum of $10k a year in these bonds.

Why not throw retirees a bone and lose the cap until inflation comes back down?

Sure, not everyone has that much money but it seems like these kinds of moves could help people psychologically until inflation subsides a bit.

And if people are really worried about too much money sloshing around in the system the government could always raise taxes.1

We don’t need a recession for a sake of a recession. Putting millions of people out of a job so we can tame inflation seems a tad premature. That nuclear option is always on the table. There’s no reason to play that card 8 months into an economic situation we’ve never seen before.

The government should do whatever it can to fix the supply imbalance to keep the economy strong.

Michael and I talked about inflation, Series I bonds and more on this week’s Animal Spirits video:

Subscribe to The Compound so you never miss an episode.

Further Reading:

Some Thoughts on the Highest Inflation Rate in 30 Years

Now here’s what I’ve been reading lately:

- When is enough money, enough? (Female in Finance)

- Looking long (Humble Dollar)

- The remarkable evolution of Tom Wambsgans (The Ringer)

- Yes, sabermetrics ruined baseball (FdB)

- The age of financial misinformation (Of Dollars & Data)

- How not to invest (Irrelevant Investor)

- 6 rules for avoiding market panic attacks (A Teachable Moment)

1Ok, no one would go for this but it is an option.