Vanguard and iShares basically killed the star mutual fund manager in recent decades.

But if anyone deserves that title right now it has to be Cathie Wood from ARK Investment Management.

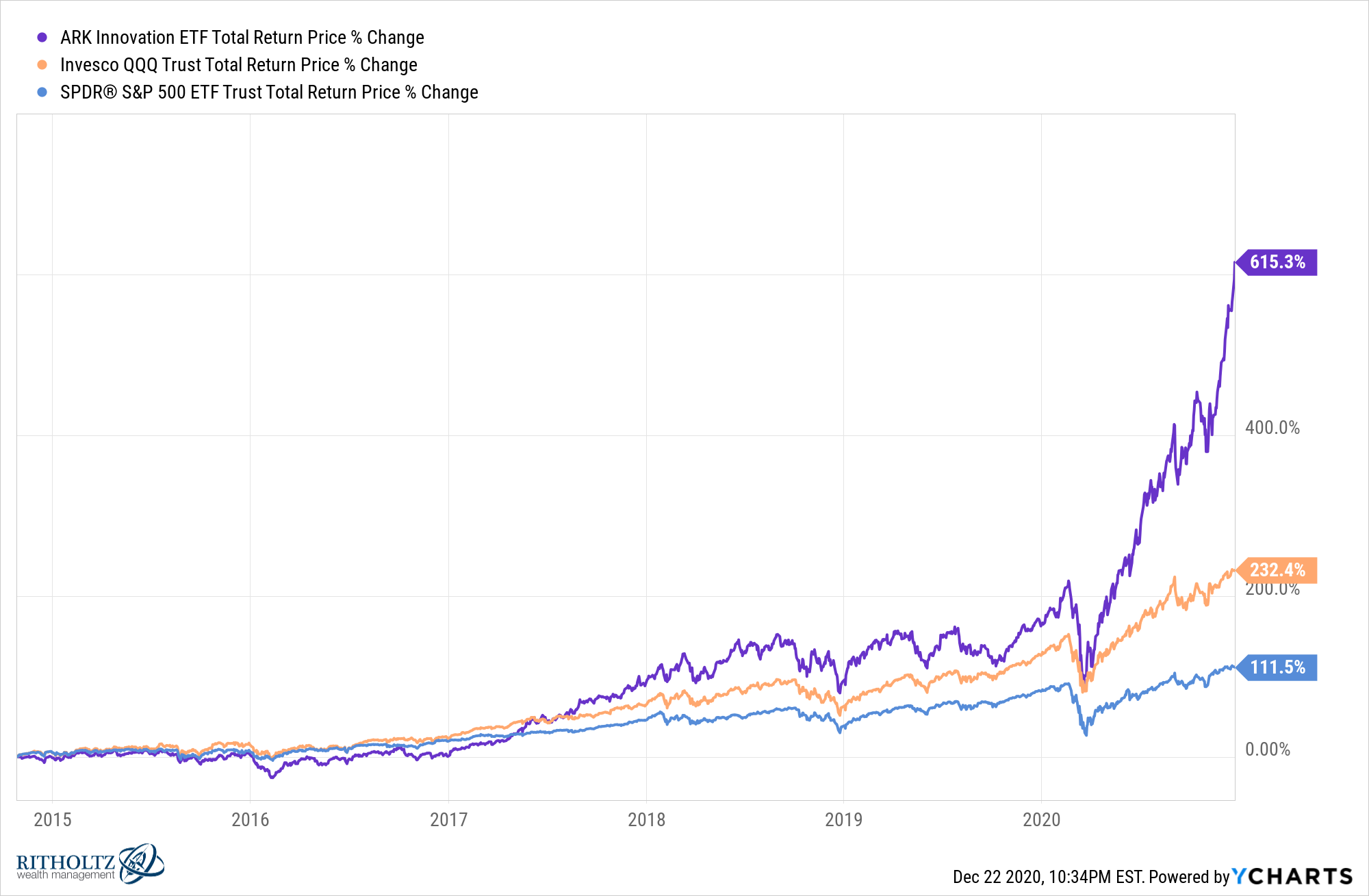

The track record for her ARK Innovation ETF is unreal:

The Nasdaq 100 has been next to impossible to beat these last few years because of the heavy concentration in big tech yet ARK’s performance makes it look quaint by comparison.

Wood has made even more concentrated bets in certain areas of tech and it’s paid off handsomely.

ARKK has been outperforming for a number of years now but you can see things have really ramped up since the bottom earlier this year in late-March.

Investors have taken notice based on the flows into the fund:

These numbers are massive for a non-Vanguard/iShares fund provider and an active one to boot.

The growth in AUM is even more striking than the fund performance:

While the fund is up 170% this year, the assets under management are up nearly 900%.

Investors have an awful track record when it comes to chasing the hottest funds of the day.

Let’s take a stroll down mutual fund lane to see how this has played out in the past.

In Big Mistakes, Michael Batnick profiles Fidelity’s Jerry Tsai, who was basically the first star fund manager in the Go-Go Years of the 1960s.

Investors went crazy for mutual funds in general as total fund assets grew from a little over $1 billion in 1946 to over $35 billion by 1967.

But Tsai stood out from the crowd. After a run of outperformance that began in 1958, Tsai saw the number of shareholders in his fund sextuple from 6k to 36k from 1960 to 1961.

After leaving Fidelity in the mid-1960s to start his own fund, Tsai got crushed in the bear market of 1968-1970 which saw momentum stocks get killed.

Assets fell 90% over the next few years and Tsai’s fund would go on to have the worst 8-year track record of any mutual fund in history to that point.

Peter Lynch ruled the 1980s and for good reason. From the late-1970s, when he took over the Fidelity Magellan Fund, through his retirement in 1991, Lynch returned close to 30% annually.

Unfortunately, the majority of investors in the fund received far less than Lynch’s 29% annual gains. It’s been said the average investor in his fund earned just 7% per year, far less than the returns of the fund itself or the overall market because they rushed in after performance was good and redeemed the fund whenever it underperformed.

By the tail end of the 1990s, the biggest star fund manager was anyone managing a tech concentrated growth stock fund because investors became enamored with Internet companies.

Maggie Mahar profiled an individual investor in one of these funds in her book Bull; A History of the Boom and Bust, 1982-2004:

Ed Wasserman took the bait only at the very end of the decade. In the spring of 2000, the 50-year-old business writer finally broke down and invested in a hi-tech fund. “By disposition, I’m a value investor,” said Wasserman. “I had a lot of skepticism–but finally, I succumbed. In the spring of 2000, I went into my local brokerage firm and said to these guys: “‘Why did I only make 12 percent last year, when other people are making 40 percent.’ And they said, ‘We have this very aggressive fund…’

That aggressive fund would go on to lose two-thirds of its value once the market went into a freefall. Other Internet funds fared even worse.

Ken Heebner’s CGM Focus Fund was the best performing U.S. stock mutual fund from 2000-2009. He was named Morningstar fund manager of the decade for the aughts.

CGM was up more than 18% annually during a lost decade which saw the S&P 500 lose close to 1% per year. The problem is investors tended to add money after a huge year like 2007 when the fund was up 80% and pull their capital after it was down like the 48% loss in 2008.

That sell low, buy high strategy led to an average investor return of a loss of 11% annually. The best performing fund of the decade saw its own investors underperform the fund by nearly 30%.

When asked what went wrong Heebner replied, “A huge amount of money came in right when the performance of the fund was at a peak. I don’t know what to say about that. We don’t have any control over what investors do.”

Following the dot-com flameout and 2008 crash, investors became enamored with hedge fund-like strategies that could “make money in any environment.”

It’s a great sales pitch, especially when investors are so focused on environments where they can lose money.

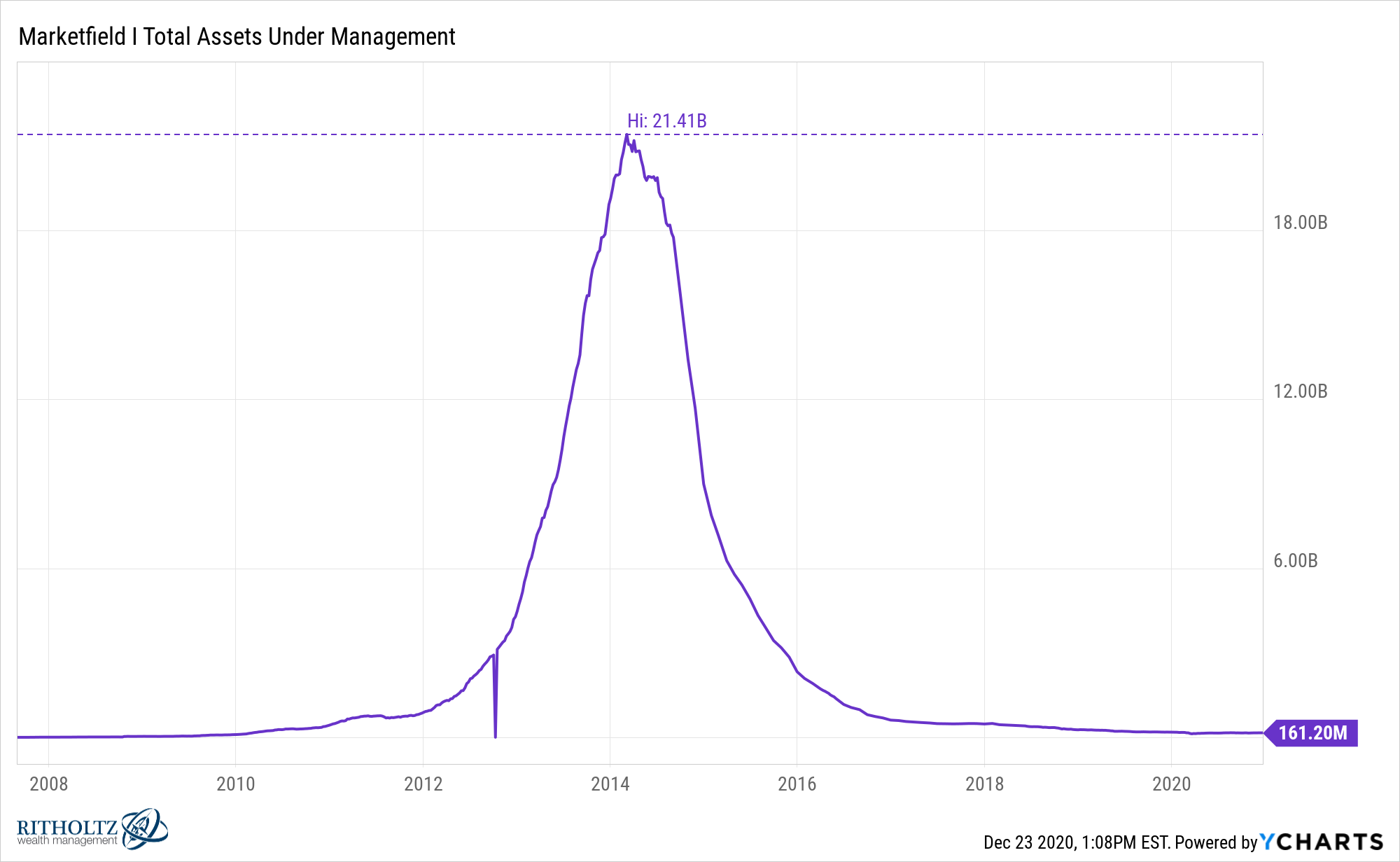

The Mainstay Marketfield Fund was a huge beneficiary of this investor demand after losing just 13% in 2008, a year in which the S&P 500 lost close to 38%. And when the fund beat the S&P 500 by 9% during the 2009 snapback rally (35% to 26%), investors piled in at an alarming rate.

Assets in the fund ballooned from just $34 million at the start of 2009 to more than $21 billion by 2014.

That money poured in just in time for the fund to underperform the market by more than 25% from 2014 through 2016. Assets left as quickly as they rushed in.

I don’t know if Cathie Wood will experience a similar drop off in performance as these examples. Size is the enemy of outperformance but you never know with these things.

However, I am fairly confident those investors now piling into her fund will almost certainly underperform the actual fund’s performance.

ARKK cannot outperform at this pace forever. There is bound to be a misstep or the style will simply fall out of favor for a period of time. Many of the investors chasing the hot dot will head for the exits at that point.

Investors don’t have a great track record when it comes to chasing the hottest fund of the day.

I hate to be that person, but I’ve seen this movie before and it ends with a behavior gap.

Further Reading:

When Performance Leads Assets