Here’s a wild stat from Joel Greenblatt on Masters in Business with Barry Ritholtz:

If you bought every company that lost money in 2019 that had a market cap over $1 billion, and so they’re about 261 of those and you bought every single one of those companies, you’ll be up 65 percent so far this year.

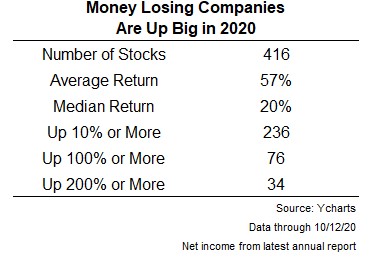

This is a crazy number so I wanted to do a deeper dive on this one. Using data from YCharts, I looked at the 2020 returns for stocks from the Russell 3000 Index with a market cap of at least a billion dollars and a negative net income from their latest annual report.

Here’s what I found:

Almost one in five of these money-losing companies is up 100% or more this year. There are some huge gainers on this list including companies like Overstock.com (+1055%), Tesla (+429%), Peloton (+348%) and Moderna (+285%).

But there are also plenty of big losers of these money-losing firms. More than one-quarter of these stocks are down 10% or more this year while almost 50 names have fallen 30% or more in 2020.

So there is a wide range of results in this dataset.

There are three different ways to think about the prevalence of big-gainers among unprofitable companies:

(1) This is ridiculous, frothy and unsustainable.

(2) This makes sense given software is eating the world.

(3) This makes sense for some companies but others are going to get their comeuppance.

Ben Thompson at Stratechery wrote a piece about the recent Snowflake public offering which was the largest software IPO ever. The company is now valued at nearly $70 billion despite losing close to $180 million in the first half of the year. Trying to square this equation makes little sense at face value until you understand why it makes sense for Snowflake to lose money right now.

Thompson describes the SaaS (software as a service) business model as, “you’re not so much selling a product as you are creating annuities with a lifetime value that far exceeds whatever you paid to acquire them.”

For this type of business model, counterintuitively, losses can be a good thing assuming they’re able to build this annuity stream of future revenues. Thompson explains:

Think about this in the context of Snowflake’s business: the entire concept of a data warehouse is that it contains nearly all of a company’s data, which (1) it has to be sold to the highest levels of the company, because you will only get the full benefit if everyone in the company is contributing their data and (2) once the data is in the data warehouse it will be exceptionally difficult and expensive to move it somewhere else. Both of these suggest that Snowflake should spend more on sales and marketing, not less:

-

- Selling to the executive suite is inherently more expensive than a bottoms-up approach.

- Data warehouses have inherently large lifetime values given the fact that the data, once imported, isn’t going anywhere.

To that end, Snowflake was an attractive investment not simply because of its eye-popping growth numbers, but also because of its eye-popping losses. That is exactly what you want to see in a business that is selling lock-in, and it isn’t a surprise that Snowflake’s IPO was massively successful.

When you look at things through this lens, it makes perfect sense that certain businesses would see extraordinary gains in 2020 despite losing money. The present value of a stock or business comes from its discounted future cash flows. So investors aren’t as worried about current cash flows but how spending now will impact cash flows in the future. Investors who focus exclusively on the current results miss the forest for the trees.

The problem for many of these stocks will come if and when some of these companies don’t meet their expectations for the future.

Greenblatt thinks it won’t necessarily be the Amazons and Googles of the world that will come back to earth but those companies people are betting on becoming the next Amazons and Googles of the world:

I don’t think the froth is in the Google, Amazon and — Amazon. Those are some of the best businesses we’ve ever seen in our lifetime.

The froth in the market is in the hundreds of companies that I was talking about before, that people will think will rhyme with the next Amazon, Google and Microsoft. And there just can’t be hundreds of companies that do that. So I think that’s where the comeuppance will be.

I tend to agree with both Thompson and Greenblatt here.

You shouldn’t be surprised so many SaaS companies are seeing huge stock market gains despite huge losses in their businesses. This is the nature of these businesses and people who are stuck using old fundamental valuation frameworks likely missed the boat on many of these companies.

But you also shouldn’t be surprised when investors set their expectations far too high for many of these stocks. Emulating Amazon, Microsoft, Google, Apple and Facebook will not be easy. These are some of the biggest and best companies in the world for a reason.

So the fear-mongering about companies with huge losses driving the stock market is misplaced but not everyone can become the next Amazon.

Further Reading:

The 2 Variables That Drive Stock Prices