The first investment I ever made was a boring old certificate of deposit.

I’m such a rebel.

I took some of the money I made from my summer job bussing tables at a restaurant and put it into a CD at the local bank. I remember being disappointed they were only paying me 5% on the $1,000 I handed over. Fifty bucks a year wasn’t all that exciting.

Investors would kill for $50 a year for every $1,000 in savings right now.

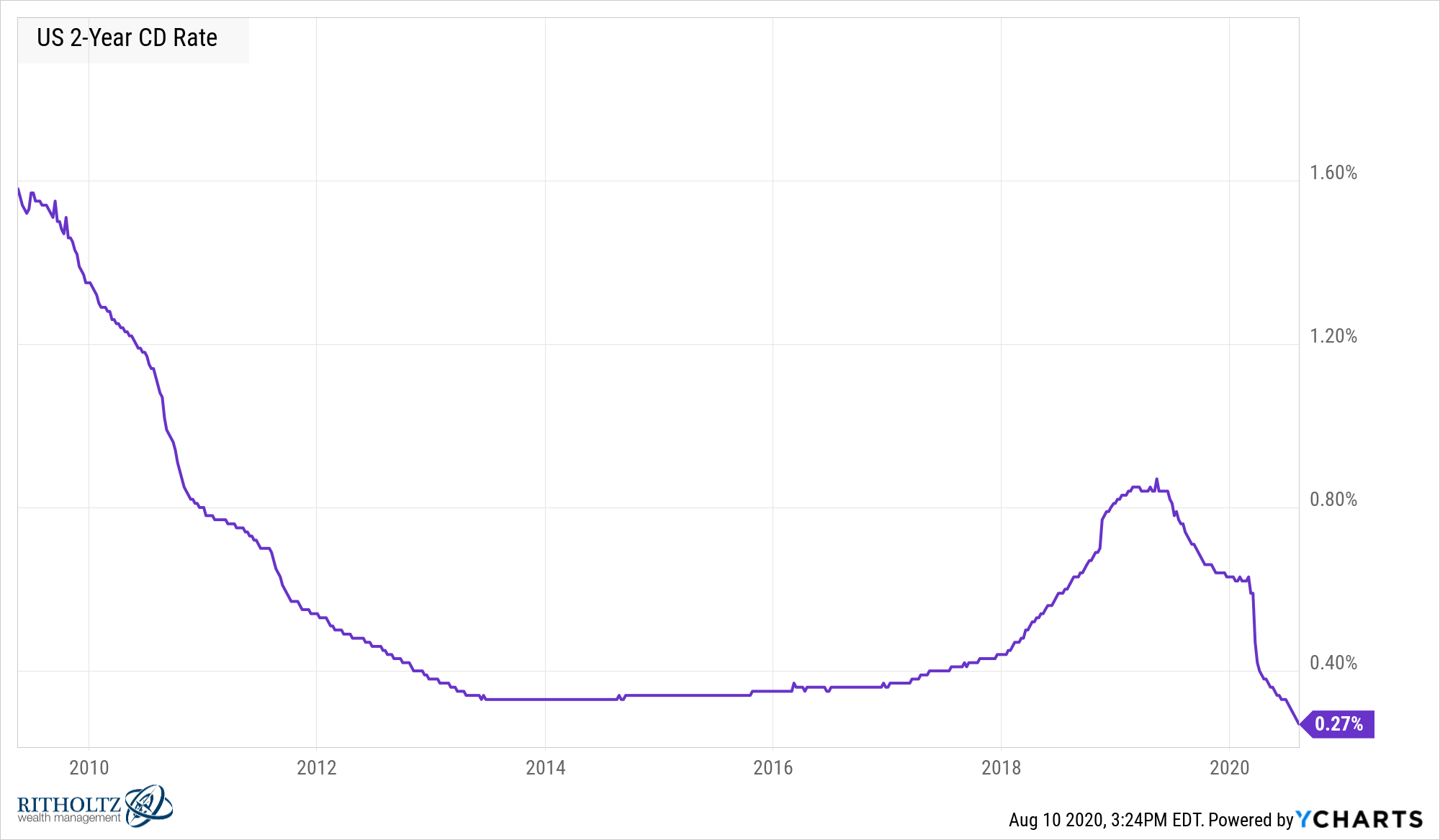

The current average for a 2-year CD pays more like $2.70 per $1,000 invested:

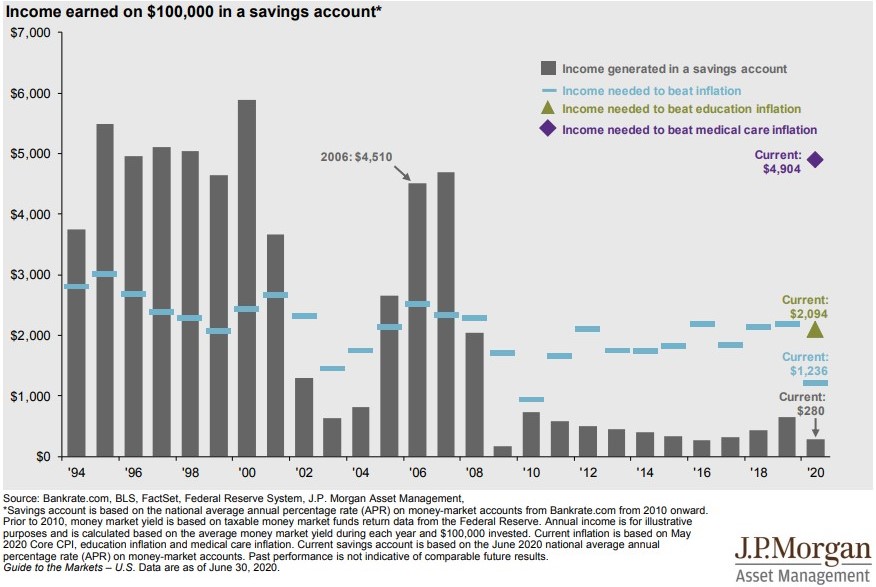

Savings account yields don’t exactly stack up when measured against historical rates either. This chart from JP Morgan shows income earned on $100,000 in a savings account going back to the early-1990s:

Throughout the 1990s you could earn around 5% on a money market or savings account held at your bank. Yields were close to this as recently as 2007. Then the Great Financial Crisis hit and yields have been in the penalty box ever since.

Here’s what the annual payout would have been on $100,000 in savings over time:

1996 – $5,000

2000 – $6,000

2006 – $4,500

Now – $280

Today’s paltry yields don’t come close to covering taxes and inflation.

Looking at these number brings up some questions:

What if we never go back to the halcyon days of risk-free income on our savings?

Why should people earn so much money on money that takes no risk?

How do retirees find safe income from their investments in a world with no safe yield?

Which one would you rather have — a higher yield on your savings account or a lower yield on your debt?

The first question is unanswerable because we don’t know what the future holds. Maybe we find ourselves in a situation in the years ahead where interest rates rise because of higher economic growth or rising inflation.

I also think it’s possible low rates could be with us for a long time so it’s important to plan for that possibility as a saver.

The second question is more theoretical in nature. As societies mature and gain more wealth, interest rates tend to come down. This happened to the Romans. It probably happened to the Lannisters and Starks too.1

There is a glut of both savings and debt in wealthier nations right now so it wouldn’t surprise me to see interest rates stay low for a very long time, even if there are some spikes along the way.

The last two questions are all about context and circumstance.

If you’re someone in or approaching retirement you’re not thrilled at the prospect of earning less than 1% on government bonds or FDIC-insured savings account.2

There are no easy answers when it comes to finding income in your portfolio these days. While it would be nice if retirees had the option of stashing their cash in a money market earning 5%, we have to invest in the markets as they are, not as we desire them to be. So today you pays your money and you takes your choice.

Young people look at today’s minuscule savings account yields and scoff at the fact older generations could actually earn something on their cash above the rate of inflation. Young people are certainly at a disadvantage in a number of ways to their parent’s generation.

But I don’t think savings account yields should be a place Millennials and Gen Z direct their ire. The other side of low savings account yields is low borrowing rates:

You can’t have generationally low mortgage rates without generationally low savings account and bond yields.

The average 30 year mortgage rate in 1996 was 7.8%. In 2000 it averaged 8.1%. By 2006 the average going rate was 6.4%.

The spreads between savings and mortgage rates were much closer back then but younger people as a whole will see far more benefits over time from lower borrowing rates than high savings rates.

Let’s be realistic — most people don’t keep six-figures in a savings account but plenty of people have six-figures in mortgage debt.

The median average home price right now is $320,000. Assuming a 10% down payment, taking on a 30 year mortgage for $288,000 at 3% would mean roughly $150,000 of interest payments over the life of the loan.

That same mortgage using a 6% borrow rate would lead to more than $333,000 in interest payments (meaning today’s rates lead to a savings of more than $180k). At 7%, it would be more than $400,000 in borrowing costs ($250k in savings). An 8% mortgage is closer to $475,000 in interest payments ($325k in savings).

Let’s say you keep $25,000 in your rainy-day savings account. Assuming you never touched this money (not realistic for a savings account but just go with it) for 30 years, at a 5% interest rate you would make around $80,000.

Lower borrowing costs will benefit young people far more than a higher yield on their savings account.

How you feel about the current rate situation has a lot to do with where you are in life.

If you’re a retiree who has their mortgage paid off and just needs their portfolio to throw off some income, you’re none too pleased with where rates are.

If you’re a young person who is borrowing money to buy a home, you should be thrilled with where rates are.

Yes, it’s harder to earn risk-free interest on your savings but the amount you can save over the lifetime of a loan can more than make up for lost interest income.

Further Reading:

How Millennials Can Close the Generational Wealth Gap

1Game of Thrones was historically accurate, right?

2You can find higher yields at online banks but those rates will continue to come down as long as the Fed keeps short-term rates low. And you can find higher rates at credit unions as well but those balances are typically capped. For example, I can earn 3% on checking at my local Lake Michigan Credit Union but only up to $15,000. The difference between 3% on $15,000 and 1% on $15,000 is $300 a year, not exactly life-changing money.