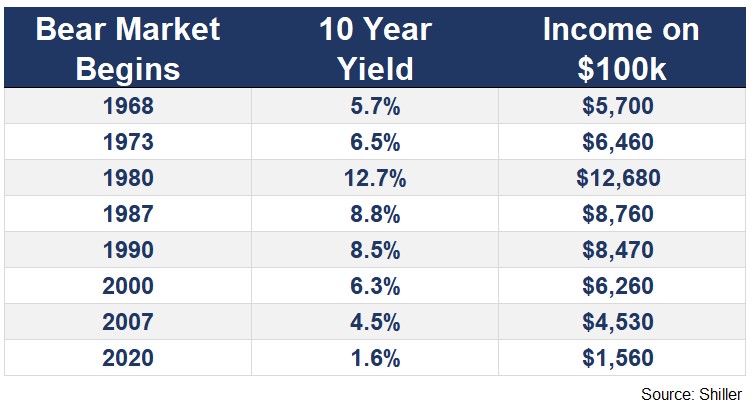

The peak of the stock market before the 1987 Black Monday crash came in August even though the pummeling itself didn’t occur until October.

When the S&P 500 peaked that August the 10 year treasury yielded 8.8%. By the time October rolled around the benchmark U.S. government bond was yielding 10.2%.

Can you imagine earning more than 10% on a “riskless” government bond today?!

Prior to falling more than 36% from 1968-1970, the 10 year yielded close to 6%.

Before the S&P 500 was cut in half in 1973-1974, government debt yielded 6.5%.

In the nasty recession that began in 1980, which saw the S&P 500 fall close to 30% by 1982, you could have gotten nearly 13% for simply buying a 10 year treasury bond.

Stocks fell roughly 20% in 1990. Heading into that bear market bonds paid almost 9%.

Bond investors could have lent to the government at more than 6% when the dot-com bubble blew up in early-2000.

Even before the Great Financial Crisis in October 2007, high-quality bonds were fetching almost 5%.

When the stock market peaked in late-February earlier this year the 10-year was paying less than 1.6%.

U.S. stocks have never gone into a crash with lower rates than we had this year. And, as with most bear markets, the flight to safety has pushed those yields even lower (currently less than 0.7%).

To get a better sense of the difference between market crashes over the past 50+ years and the current iteration, here’s a comparison of the rates at prior peaks along with the annual income being paid out on a $100,000 investment for 10-year treasuries:

I’m stating the obvious here but maybe people are overcomplicating things when it comes to looking for reasons the market has been so resilient during this crisis. What if interest rates are the Occam’s razor here?

I’ve looked at all of the other reasons the stock market has held up better than expected during a massive economic contraction:

- Concentration in tech stocks at the top of the market

- Massive stimulus from the Fed and federal government

- The forward-looking nature of the markets

These factors are likely all playing a role but the fact that bond yields are so low may be the simplest of all explanations as to why the stock market hasn’t fallen further.1

All of the world’s investable assets have to go somewhere. Every portfolio in the world is made up of some combination of stocks, bonds, cash and other assets.

Investors can always go to cash and the numbers show there was a record surge in money market inflows last month. But think about all of the money invested by pensions, endowments, foundations, sovereign wealth funds, family offices, highly paid corporate executives and wealthy individuals. Do you think all of those investors are going to sell their risk assets to move into government bonds or cash that’s yielding nothing?

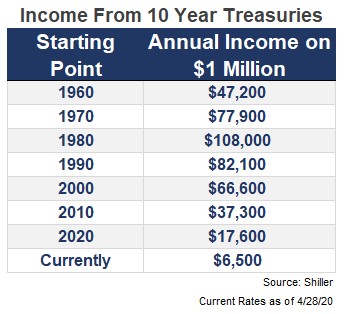

Just look at the paltry income provided by 10 year treasuries on $1 million now versus the starting point of every decade since 1960 and where we stand today:

In the past, you could legitimately move to the beach and live off the interest of default-free government bonds.

I don’t know too many people who can live on 65 basis points of income a year.

There are many reasons interest rates are so low right now other than the flight to quality. Demographics, the Fed, low inflation, a huge number of retiring baby boomers, negative rates in other countries, lower economic growth from a maturing economy and a host of other issues help explain why rates have been falling for 4 decades and are fast approaching 0% (or lower).

Does this mean stocks can’t or won’t go lower?

Of course not. The market fell nearly 35% in the blink of an eye at the outset of this crisis. I’m not suggesting low interest rates can prop up the stock market forever or completely abolish volatility.

In fact, just the opposite. I think interest rates on the floor will invite even more volatility into the fray, both to the upside and the downside. We could see many more booms and busts because of the interest rate environment, they just might be smaller in magnitude than they were in the past.

Low rates will also likely lead to a market that doesn’t always make sense.

Valuations aren’t always going to make sense in this environment.

The stock market’s ups and downs aren’t always going to make sense in this environment.

Investor actions aren’t always going to make sense in this environment.

Risk appetites aren’t always going to be aligned with portfolio allocations in this environment.

The fact that investors no longer have a safe haven where they can earn decent rates of interest will have many unintended consequences.

I’m not the first person to discuss a possible TINA (there is no alternative) marketplace. But I think people underestimate how a dearth of yield in high-quality bonds has changed the incentives and risk equation for numerous investors.

We have never seen interest rates this low. Don’t be surprised if this leads to more surprising outcomes because investors have never navigated markets like this before.

Further Reading:

Why I’m More Worried About the Bond Market Than the Stock Market

1…yet (just covering all my bases here).