A podcast listener asks:

A question I was thinking of during this market selloff: Would you recommend younger investors (say, 22-29 years old) be invested 100% in stocks or would you recommend a relatively more conservative portfolio (90/10, 85/15, 80/20, etc) to capitalize upon drawbacks like this.

Michael and I took a stab at this one on the podcast this week:

My own retirement assets have been basically 100% in stocks since I began investing in 2005-ish.1

The past 10 years or so have felt pretty good because of this but the financial crisis was another matter.

My saving grace during the equity route from late-2007 through early-2009 was I was losing a big percentage of a small amount of money.

Plus when you’re young you have a number of advantages when it comes to accepting equity risk:

- You have decades ahead of you to allow your money to grow.

- Human capital is by far your biggest asset.

- You have the ability to recover from a number of bear markets.

- You’ll be a net saver for years to come so lower stock prices are your friend (assuming they’re eventually followed by high returns at some point down the line).

In The Ages of the Investor, William Bernstein looks at investing through the lens of your investment lifecycle:

It’s virtually impossible for young workers to deploy their investment capital too aggressively, because their human capital overwhelms it. Contrariwise, in later years aggressive investing may place an otherwise secure retirement at risk.

So where you are in your investment lifecycle should play a huge role in determining your risk profile. Risk for the investor requires context. Falling stock prices are an opportunity for young investors and a potential fear factory for retirees.

Time horizon, risk profile and human capital aside, some young people simply cannot stomach the inherent ups and downs of the stock market. The problem is when stocks go down, they tend to dominate portfolio risk. So a small-ish allocation to bonds doesn’t help dampen the volatility all that much.

Bonds can play a key role in the portfolio by providing stability and dry powder during a falling stock market but when you’re young a decent savings rate can act as its own portfolio stabilizer.

Dollar-cost averaging can provide stability to a smaller portfolio because your savings will offer far greater growth in the early years of a portfolio than your investment gains.

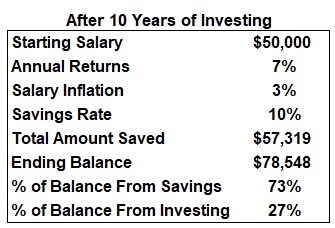

For example, let’s assume you start saving 10% of your $50k salary at age 25. Assuming a 7% annual return and 3% annual standard of living raise, 10 years into your investment lifecycle this is the breakdown of the gains in your portfolio over your first decade:

Nearly three-quarters of your portfolio’s balance in the first 10 years comes from how much you save. Even 20 years in, savings would account for more than half of your ending balance. Compounding is typically back-loaded.

And even if you’re an amazing investor, earning 12% per year instead of 7%, savings would still account for nearly 60% of portfolio growth in the first 10 years of building retirement assets in this scenario.

Dollar-cost averaging also acts as a form of risk control. Bernstein explains:

As we’ve just seen, in the savings phase there’s a large margin of safety. Absent a mass extinction in the world’s stock markets, it’s almost impossible to come out behind with rigorous adherence to a strategy of periodic investment in internationally diversified equity. To reiterate, this is not the same as saying that it’s impossible to lose real value over periods as long as 20 or even 30 years with lump-sum investing in a single national market. Such a long-term loss, however, becomes much less likely with periodic investment in a single nation and is nearly impossible, short of a global cataclysm, with an internationally diversified periodic purchasing strategy. In other words, the long-term risks (as well as the returns) of lump-sum investing are far greater than those of periodic investing.

Asset allocation is still important but periodic savings can add more stability during a falling market than most young investors realize.

Portfolio choices certainly matter. So some young investors may need to take less risk to allow them to stay invested over time. As long as you’re not sticking all of your money under your mattress, the most important decision you will make as a young investor will be your savings rate.

It’s obvious, although often overlooked, that saving money is more important than investing for young people.

A falling stock market can be a gift for young investors but only if they take advantage by deploying their savings at lower prices.

Further Reading:

When Saving Trumps Investing

Now here’s what I’ve been reading lately:

- Bring me sunshine (Monevator)

- Redirect your fear into something more productive (Abnormal Returns)

- 3 reasons you should invest in bonds (Dollars and Data)

- Larry David’s curbed sports disappointments (The Ringer)

- What dancing and investing have in common (Real Smartica)

- 7 must-read Reddit threads about finance (I Will Teach You To Be Rich)

- Some wonderful perspective on the market carnage (Albert Bridge)

- Falling knives (Irrelevant Investor)

- What if mortgage rates drop after I lock in my loan? (Basis Point)

- The global impact of the largest influenza outbreak in history (Our World in Data)

1I say basically here because I do have some trend-following strategies that will shift from stocks to bonds occasionally.