On a recent episode of the Odd Lots podcast, Tracy Alloway sat down with her Bloomberg colleague Eric Weiner to discuss the history of Wall Street.

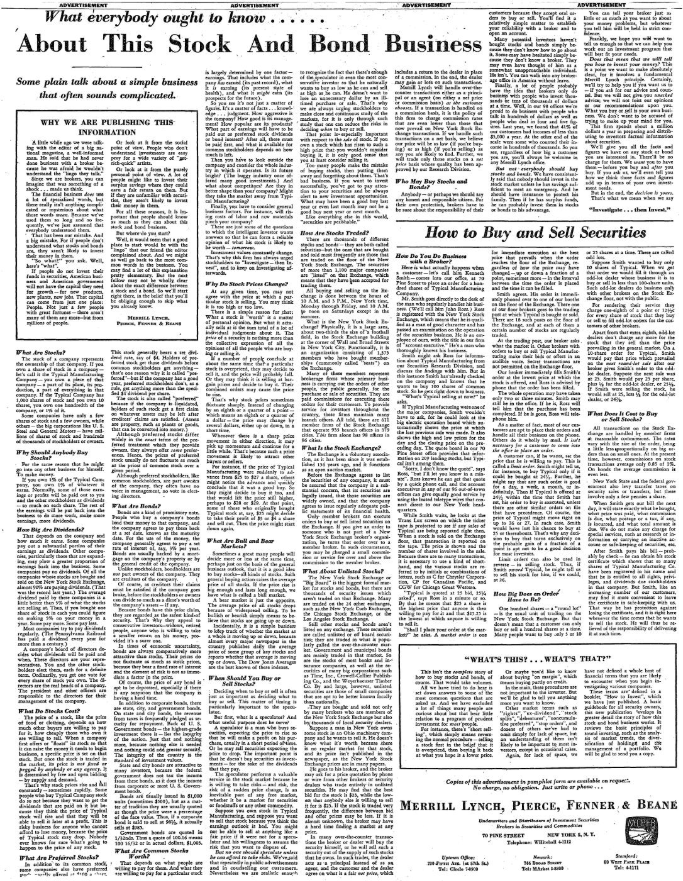

They tell the story of Louis Engel, an executive for Merrill Lynch who created the first modern advertisement for an investment firm in 1948.

Following the Great Depression, most people wanted nothing to do with the markets or Wall Street because the scars ran deep from the carnage of the market crash. Merrill Lynch was the first firm to feel comfortable enough to dip their toe back into the water by placing an ad in the New York Times.

I went to the handy New York Times archive and pulled up the paper from October 19, 1948, and found the ad on the very last page:

It’s not what I expected.

This isn’t an ad like we’re used to seeing today, but more of a full-length article. It was close to 7,000 words but apparently, that’s what founder Charles Merrill wanted.

It was expensive but it was a huge success. Merrill said they received more than 3 million responses to the ad, which gave their brokers millions of prospective clients.

I went through the entire piece to see how they approached the markets in the 1940s. The one thing that stands out is how little selling is involved. It’s more of an explainer piece than a typical advertisement pitching services.

For instance, I like how they explained the importance of understanding how investments work:

Some things never change.

They also talked about the importance of viewing stocks from the perspective of a business owner:

The behavioral component of the moves in stock prices was also explained nicely:

There’s been a lot of talk lately about the shrinking number of companies listed on the U.S. stock exchanges. Today there are roughly 3,400 publicly traded stocks (and another 10,500 that trade OTC) but back then there were just 1,100 names:

It’s also interesting to note the when the buying and selling was done back then. The stock market was open for a half day on Saturdays most of the year (I believe until the 1950s or so).

Merrill wasn’t exactly preaching a buy and hold approach but I guess I can’t blame them since they were selling brokerage services that make money from trading:

They did touch on personal finance which you don’t see from too many asset managers these days:

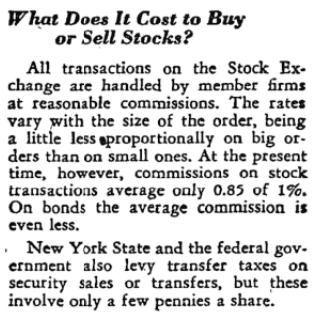

One of the biggest differences between now and then is the cost of doing business in the stock market. Look at the fees charged:

They were charging 85 basis points per trade in 1948 (along with a transaction tax I’ve never heard of before). I’m sure other brokers charged even more.

This gets back to my point that while gross returns very well may be lower going forward, investors are so much better off on a net basis, after accounting for all costs, that the end investor may come out the same on an overall net basis.

I would venture to guess few, if any, retail investors will pay for trades in 5 years or so. Brokerages will earn money elsewhere but it won’t come through retail trading commissions.

Source:

How Wall Street Started Selling You Financial Products (Odd Lots)

Further Reading:

“The market is rolling simply because it’s rolling”

Now here’s what I’ve been reading lately:

- Hubris always seems ridiculous until it’s our own (Financial Bodyguard)

- A portfolio is not a plan (Reformed Broker)

- The courage to fix the NBA’s mental health problem (ESPN)

- 5 writing tips to sound more eloquent (Dollars and Data)

- Thaler, Fama and the Freakonomics guy all golf together (Golf Digest)

- Chasing yield is as old as financial instruments (Jamie Catherwood)

- What are your investing superstitions? (Belle Curve)

- Will indexers cause the next crash? (Big Picture)