My column for Bloomberg this week looked at how the lump sum vs. dollar cost averaging decision may be impacted by the current higher-than-average valuation levels.

Investing a large slug of cash is never an easy decision. Investors worry about investing all their cash right before a market crash or not investing it all at once and missing out on further gains. So it goes.

There is no right or wrong answer, so the most important thing to do is have a plan of attack and stick to it no matter what. This is easier said than done since emotions often override analytics in the markets.

There was some research from this piece that was left on the cutting room that I thought was worth sharing.

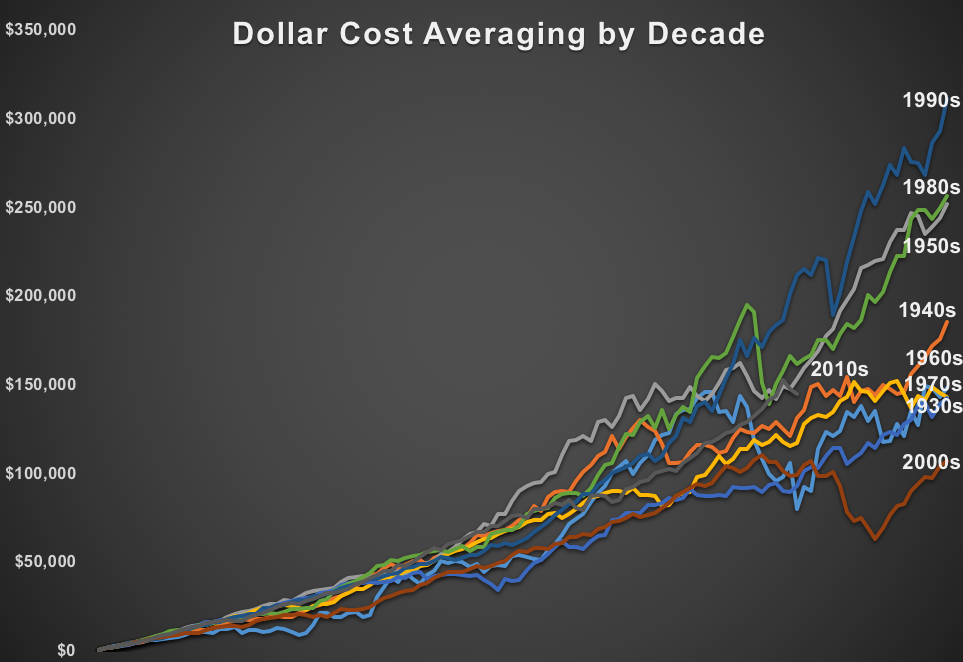

I wanted to show how market conditions can affect the end results of an investor who periodically invests in the stock market over time. Leaving aside taxes, costs, inflation, etc., I ran the numbers by decade going back to the 1930s to see how much money an investor would have ended up with by investing $10,000 each year on a monthly basis (or $833/month) in the S&P 500.

Here are those results (stating the obvious, the 2010s still have a couple years to go):

You can see how well things went in the high-flying 1950s, 1980s, and 1990s. On the other hand, the 1970s, 1930s, and 2000s weren’t as kind to investors. There is obviously a wide range of results depending on the starting point.

I found it surprising that the numbers worked out better in the 1930s than they did in the 2000s. Maybe this is one of the reasons so many investors have been skeptical of the entire stock market recovery since early-2009. We had just witnessed the worst decade of investing since the Great Depression.

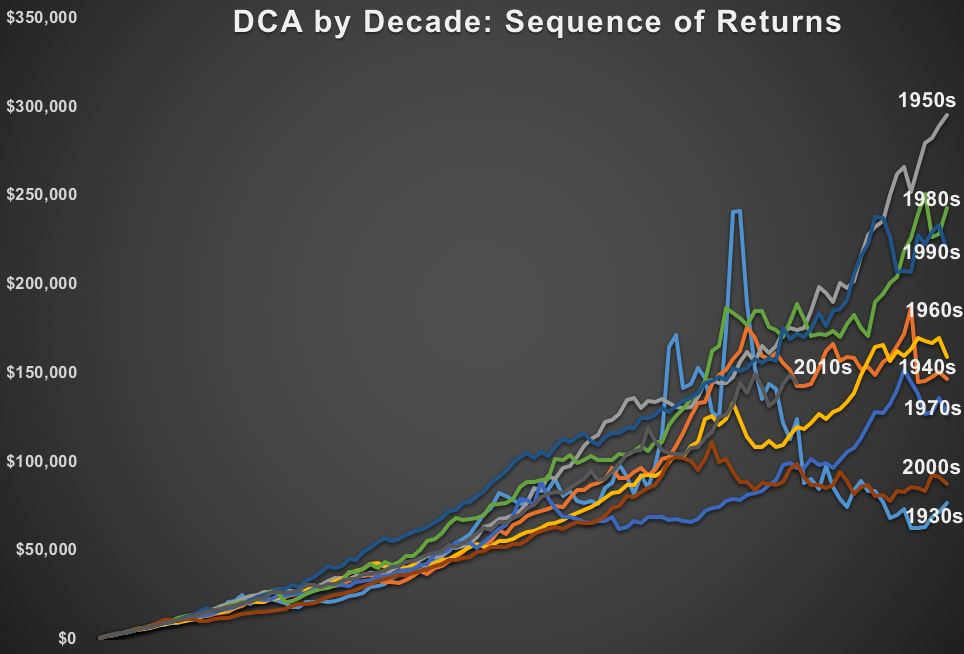

So much of any investor’s experience in the markets can be the result of the luck of the draw. Not only do the returns matter when investing periodically (or taking distributions) in the markets, but the timing of those returns matters, as well.

This sequence of returns risk can be illustrated by performing this same exercise by dollar cost averaging into the market but simply reversing the return stream (so showing what would happen if you simply reversed the order of monthly returns each decade):

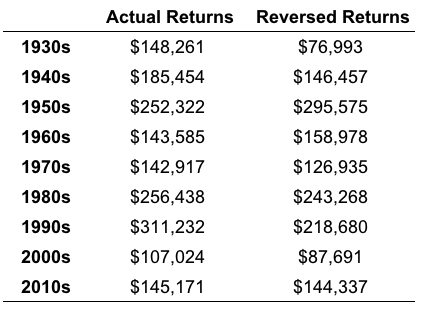

Here are the ending balances under each scenario:

The 1930s is the one that stands out to me but even the 1990s decade would have led to a much different experience for the periodic investor had the high returns of the end of the decade occurred at the outset.

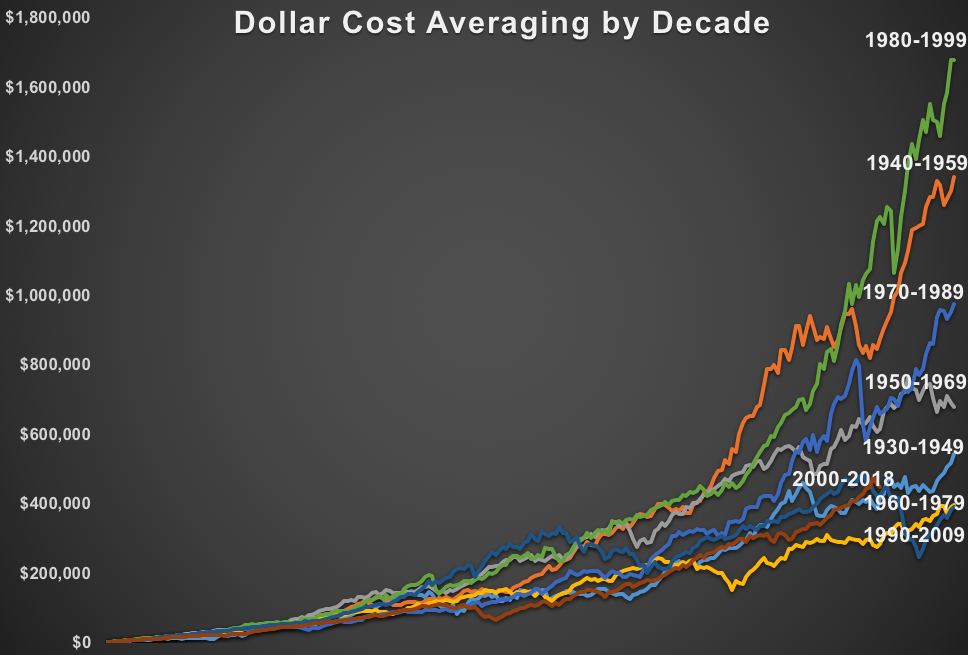

I also took things a step further to see how things would have looked going out another 10 years from the start of each decade:

The unbelievable returns of the 1980s and 1990s made for the best combination but you can also see how some of the better-returning decades balanced out the poor-performing environments and vice-versa. There was still a wide range of outcomes but this gives you a sense of how random the investment process can be in any one market.

Some investors are luckier than others based on when they’re born while others are forced to invest in markets environments that aren’t very helpful. Dollar cost averaging isn’t a perfect strategy but no perfect strategy exists. And for many investors, a DCA approach isn’t a choice but a reality when investing out of their paycheck into retirement accounts.

No one can control which type of investing environment they’re in at different stages of life but there are a few things that help deal with the randomness of the markets:

- Diversify broadly by asset class and strategy.

- Update your financial plan as expected returns turn into actual returns.

- Try to keep your turnover and fees as low as possible.

- Take advantage of tax-deferred accounts.

- Adjust your savings rate as needed.

- Build in a margin of safety to account for the possibility of a market shortfall.

- Avoid making your situation worse through behavioral mistakes and performance chasing.

- Remember that creating an investment plan is easy; it’s the implementation of said plan that is the real value-add.

Further Reading:

Mean Reversion From the Lost Decade