Lynn Hill is a world-renowned rock climber. Widely regarded as one of the sport’s best climbers in the 80s and 90s, she won more than 30 international climbing titles.

In the summer of 1989, she was about to climb what she termed a “relatively easy” route in France. At the base of a cliff she threaded her rope through her harness but instead of tying off the knot she noticed her shoe was untied. She then absent-mindedly forgot to knot the rope and returned to her climb. Once she made it all the way to the top she leaned back to rappel back down and the rope instantly unraveled from her harness, sending her flying backward 85 feet to the ground.

This mistake could have taken her career, if not her life. She was lucky enough to be saved by some tree branches and suffer only a broken ankle, dislocated arm, and a host of bumps and bruises.

After the accident Hill told the New York Times:

”It took a lot out of me to get better again, physically and psychologically,” Hill says. ”It forces you to re-evaluate everything.” During that process, she says, she never wanted to drop out of climbing. ”We’re all vulnerable,” she says. ”We could die any minute. People like to control all the things they can, but there’s risk in everything. The accident made me look at that vulnerability that we all face, and I pulled myself together to try to come back.”

Hill was one of the best at what she does in the world. This mistake wasn’t caused by a lack of training or ability. In fact, it’s possible that her expertise and experience as a climber contributed to her accident. I’m sure she did most of the simple climbing tasks without even thinking about them. All it took was that one change in the system to completely throw her off.

I’m a big fan of taking big ideas from a wide range of disciplines to make better decisions. Having a system and a broad base of knowledge in place as a way to think about how the world works is a great way to deal with the uncertainties we are all forced to deal with. Mental models help set rules and boundaries around the decision-making process.

But they can have a downside if we’re not careful.

These mental models or rules of thumb can be both helpful or hurtful in the investing game depending on how they’re utilized. You can’t convince me that less is more or simple beats complex will ever go out of style. But certain investment strategies or rules certainly can and will go out of style — some for good.

From 1900 to the late-1950s, one of the best market signals was a comparison of stock market dividend yields to government bond yields. Stocks almost always yielded more than bonds so when the dividend yield dropped below the bond yield it was time to get out of the market and into the safety of bonds. Which worked until it didn’t and bonds proceeded to yield more than stocks for the next 50-plus years, thus thwarting what was seen as a can’t-miss sell signal.

The old mental model for value investing was that you could easily outperform through the purchase of cheap companies. Oakmark portfolio manager and notable value investor Bill Nygren recently gave a talk at Google where he discussed the changing nature of this mental model:

I think one of the frustrations you hear with a lot of value managers today is, what I did 20 years ago isn’t working anymore. I think that’s always been the case. What worked 20 years ago very rarely still works today. Twenty years ago you could just buy low P/E, low price to book value stocks, and that was enough to be attractive. Now, you can do that for almost no fee and the computers have gotten smarter about combining low P/E, low price to book with some positive characteristics – book value growth, earnings growth. The simple, obvious stocks that look cheap generally deserve to be cheap.

When I started at Harris 30 years ago, we were one of the earliest firms to do computer screening to find ideas. Once a month, we would pay to have a universe of 1,500 stocks rank ordered by P/E ratio. As analysts, the day that output came in, we would all be crawling all over it to look at what the new low P/E stocks were. Today, any of our administrative assistants could put that screen together in a couple of minutes. Because it’s become so easy to get, it’s not valuable anymore. I think it’s probably not just investing, that’s through a lot of industries, as information becomes more easily accessible it loses its value.

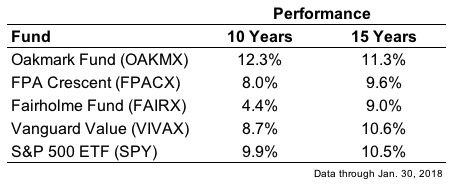

Nygren is one of the few remaining star value mutual fund managers who has been able to adapt to the changing market conditions in this environment:

Former value outperformers from FPA Crescent and Fairholme have had a much harder time keeping their long-term outperformance over the past 10- and 15-year periods. While I don’t fully agree with Nygren’s comments on quantitative investing, you can see that even the simple Vanguard Value Fund has done much better than these former top-performing funds.

There’s no reason to pay top dollar to a mutual fund manager to simply buy “cheap” stocks on your behalf when a computer can do it for a fraction of the cost and doesn’t have nearly as many built-in biases or baggage.

Nygren adapted and has been able to keep his track record intact. There are probably a lot of investors who are stuck using an old model that won’t be as successful going forward. And it’s not that they’ve become worse investors over time. It’s that relative, not absolute, skill is what matters in the markets. There are simply many more intelligent, hard-working investors now than there once were, making it much more difficult to outperform.

Investment acumen alone is not going to be enough these days if you don’t have the ability to pick up on structural changes to the system, be they minor or major.

Again, I’m a big believer in finding a framework for how the world works through the use of mental models. Understanding how to think is often more important than figuring out what to think.

But you must also have the ability to adapt to changing circumstances to avoid mistakes both big and small. I like the idea of having strong opinions, weakly held. The whole point of a mental model framework is not to be so rigid that you always do things the same way.

Having a diverse skill set can help make sense of a world that doesn’t make sense most of the time.

Sources:

Cliffhanger (NY Times)

Bill Nygren Google Talk

Further Reading:

Experts on an Earlier Version of the World

Now here’s what I’ve been reading lately:

- Guiding others to the finish line (WSJ)

- The most important idea in life (What I Learnt on Wall St)

- You are remembered for the rules you break (Reformed Broker)

- The 5 levels of investing (Graham Duncan)

- Markets can never be perfectly efficient (Irrelevant Investor)

- The best way to lose 5 billion dollars (Of Dollars and Data)

- Wash your hands before investing (A Teachable Moment)

- How Amazon might get into the healthcare industry (Stratechery)

- The behavioral benefits of trend-following (Econompic)

- “The mutual fund business used to be a business in which we sold what we made, and now we are business in which we make what we sell.” (Advisor Perspectives)