The Holy Grail of portfolio management is finding an asset or strategy that has high returns with low correlations to standard portfolio holdings like stocks and bonds. In the mid-2000s, many investors were led to believe they found such an asset in commodities.

One of the main reasons for this belief was an academic paper written in 2005 by Gary Gorton and Geert Rouwenhorst called Facts and Fantasies about Commodity Futures. Here’s the main takeaway:

We construct an equally-weighted index of commodity futures monthly returns over the period between July of 1959 and March of 2004 in order to study simple properties of commodity futures as an asset class. Fully-collateralized commodity futures have historically offered the same return and Sharpe ratio as equities. While the risk premium on commodity futures is essentially the same as equities, commodity futures returns are negatively correlated with equity returns and bond returns. The negative correlation between commodity futures and the other asset classes is due, in significant part, to different behavior over the business cycle. In addition, commodity futures are positively correlated with inflation, unexpected inflation, and changes in expected inflation.

Sounds appealing, right? The same long-term returns as stocks but with negative correlations to both stocks and bonds. WE LANDED ON THE MOON!

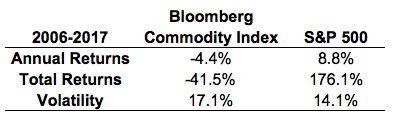

Fast forward to today and here’s how things have shaken out performance-wise since the publication of this paper (I used a January 2006 start date to keep things simple here):

Commodities have gotten crushed with higher volatility than stocks. Not only have the returns been terrible but the correlation benefits were lost during the crisis as well as commodities crashed right alongside stocks.

Now, even 10+ years in the markets is not enough to judge the performance of an asset class. Stocks have had their own lost decades in the past. But investors who took the claims of this paper at face value have to be wondering what happened.

The problem was actually sussed out at the time by another academic paper, this one written by Claude Erb and Cam Harvey called The Strategic and Tactical Value of Commodity Futures. This paper, released not too long after the Gorton and Rouwenhurst paper, drew a much different conclusion:

A number of studies have argued that commodity futures are an appealing long-only investment class because they have earned a return similar to that of equities. Focusing on the dangers of naive historical extrapolation raises a question, however, about what this historical evidence means. Does the average commodity futures contract have an equity-like return? Our research suggests it does not: The average excess returns of individual commodity futures contracts have been indistinguishable from zero. Might portfolios of commodity futures have equity-like returns? Here, the answer seems to be maybe. A commodity futures portfolio can have equity-like returns if it can achieve a high enough diversification return. The diversification return is a reasonably reliable source of return. Or a commodity futures portfolio can have equity-like returns by skewing portfolio exposures toward commodity futures that are likely to have positive roll or spot returns in the future. The challenge for investors is that, although spot and roll returns may be high in the future, nothing in the historical record gives investors comfort that future spot and roll returns will be substantially positive.

So instead of simply relying on historical performance numbers, Erb and Harvey deconstructed the entire idea of commodity futures to understand the return drivers. What they discovered is that the promised equity-like expected returns were a mirage.

Erb recently told Meb Faber in an interview that the reason he initially performed his research and wrote the rebuttal is that he met Gorton, who tried to sell him on the idea that commodity futures offered the Holy Grail (Gorton also tried to sell him a product to invest in those futures). Erb says that almost nothing in the commodity paper by Gorton made sense so he decided to perform his own research and come to his own conclusions. Erb explains:

Cam and I never found any evidence of Gorton and Rouwenhorst’s commodity risk premium. We did find that Gorton and Rouwenhorst’s commodity risk premium could have been a payoff to a rebalancing return.

It would be nice to believe that a strategic allocation to commodity futures was a bet on rising commodity prices. It is a nice belief for which there seems to be no support.

There are three ways in which you can earn returns on commodity futures:

- The price can go up.

- The term structure or roll yield.

- The rebalancing return.

This is all somewhat technical but it helps in understanding how commodity futures work. The price return component is straightforward. The roll yield refers to the discount or premium to the spot (current) price of the futures contract. The rebalancing return would come from the fact that a basket of commodities are highly volatile and rebalancing a portfolio of highly volatile, low-correlated assets can result in higher returns over time.

Investors (or more likely hedgers and speculators) in commodities in the past enjoyed a positive roll yield (meaning the futures contracts were priced at a discount to spot prices) because these markets were mainly full of corporations, commodity producers and individuals (e.g. farmers) who were hedging their exposures and trying to stay afloat. That has gone away now that there are billions of dollars of institutionalized money invested in the space. That reversal, which may or may not be permanent, has led to a negative roll yield (meaning the futures price was at a premium to the spot price).

The finance term for this series of events is that we’ve gone from “backwardation” to “contango” in the futures markets. So even if the commodities prices rise substantially you could still lose from a negative roll return (and the reason you must invest in futures in the first place is that investing in the actual physical commodities would mean taking delivery of them, storing them, etc.). Essentially, investors in commodities futures are paying a dividend instead of earning it like they do in stocks and bonds.

Of course, Wall Street is rolling out new products to account for the way these markets now work. The products will get better. But this story is more about how these ideas and research evolve over time and why the end investor is usually on the losing end of things.

The lifecycle of a novel investment strategy looks something like this:

- Early investors earn higher returns through a first mover advantage in an unproven strategy.

- Academic research papers highlight the strategy in detail and make it sound too good to be true.

- Wall Street creates a bunch of products to take advantage of said research.

- Retail and institutional investors pile in after all of the huge gains have likely already been extracted.

- Rinse and repeat.

Commodities can still earn a place in a portfolio if you know what you’re doing with them and how they typically function. In my view, they’re meant for trading, not investing and work better in a tactical wrapper rather than a strategic one.

Regardless of your feelings about commodities as an asset class, the lesson here is to always do your own homework and never take what others say at face value before making an investment.

It’s also important to understand that it’s very easy to find a strategy that did work well in the past but much harder to find one that will work well in the future. This is why it’s so important to understand your specified strategy and the built-in return drivers.

Sources:

Facts and Fantasies about Commodity Futures

The Strategic and Tactical Value of Commodity Futures

Claude Erb on The Meb Faber Show

Now here’s what I’ve been reading lately:

- The patterns that weren’t there (Of Dollars and Data)

- Ric Edelman’s favorite investing chart (Big Picture)

- Incentives and behavioral design (Dan Egan)

- The fallacy of instant success (Intelligent Fanatics)

- “The majority of stakeholder value created over the last decade has been a function of removal.” (A Teachable Moment)

- The thrill of uncertainty (Collaborative Fund)

- Why 2017 was the best year in human history (NY Times)