In the past week I’ve read three different takes on the future of interest rates that really made me think about their direction over the very long-term.

1. The first comment was a tweet from venture capitalist Marc Andreessen in reference to a discussion about the current low level of short-term interest rates being set by the Fed:

https://twitter.com/pmarca/status/614941792132149248

The risk-free rate is generally thought to be an investment with no potential for a financial loss (think your FDIC-insured savings account or short-term treasury bills). Andreessen asks why holding cash, technically a risk-less asset, should generate a return at all.

2. The next thing I read was a blog post by Paul Gebhardt that touches on the effects that innovation could have on future returns on capital:

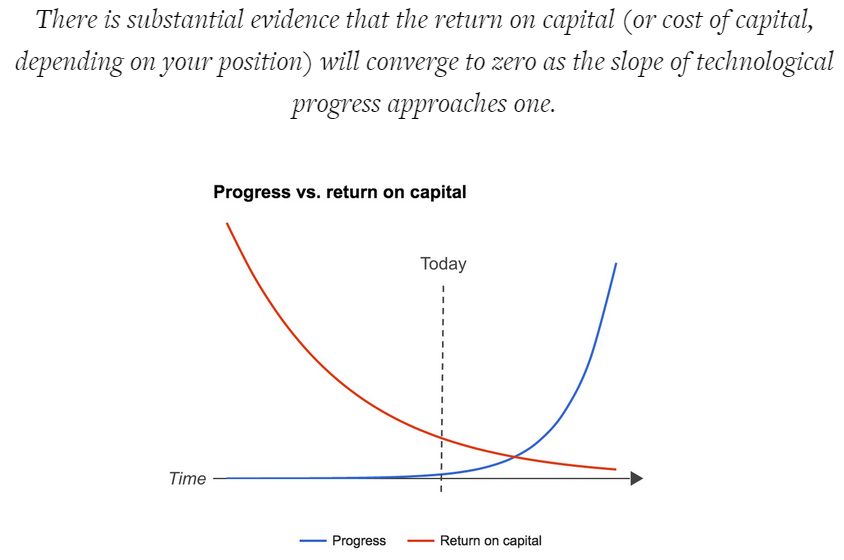

He makes the case technology makes innovation much cheaper than ever before because the costs to start a business are so much lower than they were in the past. This innovation causes an abundance of capital, which leads to lower returns on that capital.

3. Finally, I’ve been reading William Bernstein’s really interesting book, The Birth of Plenty, which tells the story of how the enormous global economic machine came to be over the past 200 years or so after basically going nowhere for thousands of years. He discusses how the maturity of an economy affects interest rates:

Interest rates, according to economic historian Richard Sylla, accurately reflect a society’s health. In effect, a plot of interest rates over time is a nation’s “fever curve.” In uncertain times rates rise because there is less sense of public security and trust. Over the broad sweep of history, all of the major ancient civilizations demonstrated a “U-shaped” pattern of interest rates. There were high rates early in their history, following by slowly falling rates as the civilizations matured and stabilized. This led to low rates at the height of their development, and, finally, as the civilizations decayed, there was a return of rising rates.

A few things to ponder based on all of this:

- If the U.S. has the biggest, safest financial markets in the world, why should investors expect to earn a high return on their cash? People seem to assume that there’s a long-term equilibrium risk-free interest rate that should allow them to earn 4-5% on their cash savings. Should they? What if those rate levels are a thing of the past?

- The Internet is the biggest deflationary invention of all-time. Will technology disrupt the financial markets over the coming decades and lead to deflation in interest rates, as well? (And is disruption the most annoying and over-used word in Silicon Valley?)

- Is the U.S. at the bottom of the U-shaped interest rate curve?

The answers to these questions are beyond my pay grade and to some extent they can’t all be true because the U.S. can’t be peaking if we’re about to experience a technological revolution in the coming decades. But from an interest rate perspective, it’s an interesting thought exercise, even if it’s something that can’t possibly be known for many years.

I’m on record saying I think those who think inflation and interest rates will never take off in the future are probably misguided. But Bernstein admits in his book that there are always fits and starts within these longer-term cycles:

For example, the apex of the Roman Empire in the first and second centuries A.D. saw interest rates as low as 4%. The above sequence holds only on the average and over the long term, with plenty of shorter-term fluctuations. Even during the height of the Pax Romana in the first and second centuries, rates briefly spiked as high as 12% during times of crisis.

One of the most heavily cited criticisms of the Fed’s zero percent interest rate policy is that “Savers are being punished by the Fed.” These people fail to mention that investing is an important part of the saving process. Anyone who’s allocated even a small portfion of their savings to the stock or bond markets the past six years hasn’t been punished. They’ve more than made up for a lack of yield on their money market funds, savings accounts or CDs.

Maybe savers have been unduly punished in this recovery. But is it also possible that savers in the past were too richly rewarded for keeping their money in unproductive savings accounts? Should investors expect to earn a decent risk-free rate of return on their assets?

Sources:

The End of Interest Rates (Paul Gebhardt)

The Birth of Plenty: How the Prosperity of the Modern World Was Created

Further Reading:

How Innovation is Affecting Market Valuations

How Often Are Markets Normal?

Interesting piece, Ben. Yes on the word “disruption”.

“unproductive savings accounts”?

You give your money to a bank & they lend it out & make a chunk and give you a chunk.

That is productive.

…and yes, the banks should not keep all of the “chunk”.

savings accounts are productive to the bank & should be productive to the lender, who is the saver.

That’s valid, which is why banks have to pay something to savers to attract deposits. Unfortunately the banks have kept everything the past few years. I’m actually a fan of the online savings accounts which pay much more than the brick & mortar banks.

I agree with both of you. I know everyone is tired of hearing people lament the repeal of Glass-Steagall… But really if retail and investment banking were separated then there would be real incentive in rewarding savings for banks underwriting loans.

Here’s an econ take from Cullen Roche if you’re interested:

http://www.pragcap.com/should-money-earn-interest-very-nerdy

I just transferred quite a bit of cash from a local bank paying me 20 bp to two online banks. One is paying 1.24%. The other paying .75% but if you have $50K with them and leave it for 3 months, they give you a $500 bonus on top of the .75%. $100 per $10K up to $50K balance. Do the math on that!

Not bad. I see no reason why anyone would want to have their savings in a money market or bank savings account at the moment (or ever). It just doesn’t make sense when there are better options out there.

[…] What if risk-free returns go away slowly (A Wealth Of Common Sense) […]

We all need to be mindful of the arc of previous civilizations and how this might affect the US over time. History seems to suggest that our role in the world, politically and economically, might diminish over time. If the Dollar was replaced as the dominant currency, it seems likely that interest rates would need to rise in order to attract capital.

As far as savers being punished by low interest rates, this has always struck me as a bit of a red herring. For (most) individual savers, a 1% rise in rates would likely improve their finances only slightly. However, the impact on financial institutions would be significant due to the increase in spread between cost of funds and earnings.

Agreed. Yet the US has many more barriers to entry to stay on top than previous regimes. Should be interesting if China doesn’t implode.

I always tell people a 1% difference in your savings account is $100/year for every $10,000. It’s not going to make a huge difference unless you have a lot of cash stocked away.

[…] is probably the best article I have read all week – What if Risk-Free Returns Slowly Go Away?. The article focuses on what could be low interest rates going into the future. The result is that […]

The idea of a “risk-free” is misleading.

As a user of a currency, I want that currency to be stable. If too much money chases too few goods, the currency becomes unstable, which is a bad thing. Therefore, as a user of the currency who cares about its stability, I would be willing to pay people not to chase more goods than there are available to be chased. I cannot personally do that, but the government, on behalf of all of us users of currency, can do it by paying interest on deposits in the Treasury, aka Treasury securities. That so-called “risk-free” rate is better understood as a “risk-independent” rate, because it is paid for not chasing goods and is only as high as it needs to be to prevent people from chasing goods.

All other users of money and credit compete with the Treasury for money, so they must pay more than the risk-independent rate being paid by the Treasury for mere non-spending. Or, as in the case of a commercial bank, they must provide a service like checking to compensate for the use of the money. The Treasury does not allow checking against your account; your bank does allow it, and that is compensation for the use of the money above and beyond what the Treasury is paying. But the point is that we reckon the return on a financial instrument in terms of the payment made to match the Treasury PLUS an amount to account for the risks taken by investing the money in a project more risky than depositing it in the Treasury (hence, the term “risk-free” rate).

What, then, determines what the Treasury should pay people for money? The answer is the amount necessary to prevent inflation by convincing people to deposit their money in the Treasury. That amount is a function of the demand that would exist, relative to the supply that could meet it, in the real economy at any time. Without trying to divine what that number should be, I think it is enough to note that it is not “inherently” positive or negative, so the rate may go to zero, and it may stay there for a long time, or it may not. But “go away” seems to me too binary a concept. Zero is just one interest rate among many, not some special condition of non-existence.

I like the description as a risk-independent rate. I guess I should have been more clear on this — I’m thinking no return above inflation. Good explanation here.

[…] Further Reading: Uncharted Territory in the Fed Funds Rate Cycle What if Risk Free Rates Slowly Go Away? […]

[…] read all the way through this Ben Carlson post, What if Risk-Free Returns Slowly Go Away?, but it wasn't until the very end that really caught my attention. "Maybe […]

[…] Further Reading: What if Risk Free Returns Slowly Go Away? […]

[…] Remember when cash equivalents used to pay interest? Can you imagine earning 5% on a money market or short-term treasury note these days like you could have in 2007? (See also What if Risk-Free Returns Slowly Go Away?) […]

[…] Remember when cash equivalents used to pay interest? Can you imagine earning 5% on a money market or short-term treasury note these days like you could have in 2007? (See also What if Risk-Free Returns Slowly Go Away?) […]

[…] Further Reading: What If Risk-Free Returns Slowly Go Away […]