When we got engaged my wife and I had a discussion about how we would run our finances once we were married. This was obviously a topic that was breached by me since I am the personal finance nerd of the relationship. But she was all for it. We covered our spending habits, budgeting, saving, debt, bill payments and how we generally planned on setting our long-term financial goals. It was a great talk and one I recommend every couple should have at some point if they plan on staying together for the long haul. Money is actually the number one cause of marital problems and divorce.

Since we both come from similar backgrounds on the subjects of saving, credit card debt and living below our means this was a pretty easy conversation considering how problematic finances can be for some couples. But there was one area where my wife needed some more clarity. And that was on how we were investing in stocks with our retirement savings.

My wife, like most normal people, did not know much about the stock market except for what she heard on the news or saw on TV or in the movies. She did not give much thought to investing in stocks. So when I told her that we would be saving the bulk of our retirement savings in stocks (especially when we were younger) she was initially a little worried.

Her main concerns were as follows: Aren’t stocks extremely risky? Isn’t there a chance we could lose most of our money? Shouldn’t we just play it safe? Other people I know use a stable value fund and they have never lost any money? I assured her that by working in the investment profession I knew what I was talking about. But I figured that a tutorial on the basics would be helpful to ease her worries.

What follows is basically the case that I presented to her. Most people just blindly go about investing in stocks (because they think they’ll make the most money that way) or bonds and cash (because they think they are safer) without ever thinking about the actual pros and cons of each option. That is the basis for this discussion.

Over the years we have been told by the professionals to expect an 8-10% annual return by investing in stocks. And if you look at the long-term rate of return on the S&P 500 (a good gauge of the overall domestic stock market) going back to 1928, stocks have returned 9.31% per year. That does not mean that is what you will get going forward, but that is what the past 85 years of stock market returns have been. Not a bad return on your capital. You can double your money in less than 8 years with that return. But you don’t just automatically book that 9.31% year in and year out.

As we know from the last decade of investing, stock returns can be all over the map. Since 1928 the standard deviation of those returns was 20.00%. That means that around the average of 9.31%, the majority of the time the returns were 9.31% plus or minus 20.00% (so in the range of negative 10.69% up to positive 29.31%, again the majority of the time). And there are always outlier years when the returns are way above or way below the averages and ranges.

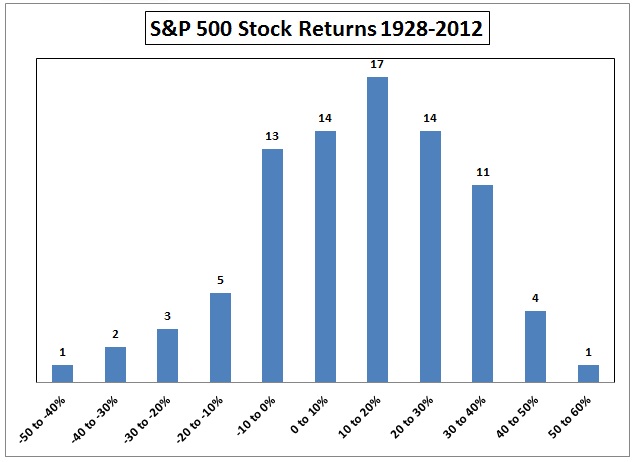

It’s a good exercise to look at how stocks have performed in the past to see how consistent the returns have been. Here is a chart that shows the annual return breakdown over the years of investing in the stock market.

As you can see there were only 14 times that the annual return was within the 0% to 10% range (less than 17% of the time). There were also 11 times (13% of the time) that the market lost over 10% with 6 of those years losing over 20%. Now remember that these are just calendar year returns. They don’t cover the times that the market reached a peak in one year and a valley in the following year (in the finance world that’s called a drawdown). That is why there are no 50% losses that show up. But those instances have happened in this period of time (during the Great Depression, in the mid-70’s and twice in the last 13 years).

It’s also helpful to look at the overall winning percentage of stocks. Since 1928, stocks have a positive annual return in 61 years against 24 years with a negative return, a 72% winning percentage. A lot of times you hear people compare investing in the stock market to gambling at the casino. That may be true if you are a day trader and play around with individual stocks. In that world there may be a game being played around you that you aren’t even aware of.

But by investing in stocks in the market as a whole through index funds or ETFs, you can see that the percentage of years that you make money far exceeds the times that you lose money. Although I consider my blackjack skills above average, I would take a 72% advantage over the house at the casino anytime. Unfortunately that’s not going to happen, so I’ll stick with stocks.

Going over the large losses was the point where my wife got nervous again. She asked, “Do we really want to risk those kinds of losses with our savings?” We were 25 and 26 when we got married. I assured her that we had 30 to 40 years until we retired (even though she hopes for an earlier exit) and then another 30 years of actual retirement after that. We could be looking at an investing horizon of 70 years or possibly longer. Plus the fact that we would be dollar cost averaging into the market by investing in our 401(k) plans on a bi-weekly basis and our IRAs on a monthly basis.

That means that when those large losses do occur we would be buying at lower prices to aid in future gains. When stocks were running higher we would be buying a lower number of shares in the funds we invest in. And having a schedule to rebalance between our diversified funds (invested across different world markets) would keep us honest by selling the winners and buying the losers, the definition of buy low, sell high that everyone knows but not many follow.

Add in the fact that we would be investing over a long time frame that would give us the best chance of getting the long term average stock market return since we wouldn’t be jumping in and out of the market over the short term hiccups.

Next I moved on to show her how inflation over the course of our careers would eat into the stable value and bond fund returns. Over the same time frame I used for stocks (1928-2012) bonds have returned 5.10% per year and cash (T-bills, a good proxy for stable value funds) comes in at 3.57% per year. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, the long-term average annual rate of inflation going back to 1914 is 3.35%. Using that 3.35% per year that inflation will eat into your investment returns gives you the following real (after inflation) returns for each asset class:

Stocks 5.96%

Bonds 1.75%

Cash 0.22%

Most people don’t account for inflation in their long term plans and that can be a mistake. It’s always best to err on the side of conservatism. If inflation ends up being lower than 3.35% per year on your cost of living, then you can just spend more money in retirement. It’s a simple fix.

The subject of inflation brings up another point about the riskiness of investing in the stock market. Many of us like to focus on the risks involved with staying in the stock market. The risk of loss or volatility in our account balances. There is also the risk of not being in the stock market which the real or after inflation return on T-bills shows you. Risk in this case deals with barley keeping up with purchasing power by having your long term funds in cash.

Stocks are the obvious winner over the long-term on an absolute and inflation-adjusted basis. To have any chance of meeting our retirement goals, we need stocks to be a meaningful part of our investments. As your career progresses and your investment balances increase and you get closer to retirement age you can slowly transition your portfolio to more stable, income-producing investments like bonds, CDs and money market funds. You must also have a detailed investment plan with an asset allocation that fits your circumstances.

I realize that investing in stocks can be nerve-racking in the short to intermediate-term. But in the eight-decade stretch between 1926 and 2010 there was not one rolling 20-year period (at any starting point) that stocks produced a negative return. Warren Buffett’s old saying that rule no. 1 when investing is don’t lose any money. And rule no. 2 is don’t for forget rule no. 1. By having a long-term outlook on your savings you can make his rules a reality. You just have to have the mindset that you are not going to make short-term decisions with long-term assets.

Someone who starts saving at age 30 and wants to retire at age 65 would have to save about $8,500 per year to end up with $1 million at retirement using the 5.96% annual stock market return over inflation. But to get that same $1 million using the after inflation bond return of 1.75% you would have to save around $20,600 a year (over 140% more). Using the real cash return on T-bills would mean you would have to save about $27,600 each year.

For those of you who would like to invest in stocks but can’t handle the extreme volatility that is inherent in the stock market, you can add some bonds in the mix to dampen the swings in your portfolio. But as we have seen over the long term bonds have generally earned less than stocks so you will probably have to save more to make up for the lower return. That is the whole reason that your risk profile and time horizon need to synch up in order to make an investment plan that you will stick to.

In the end my wife agreed with me. It was probably out of sheer boredom so I would stop bombarding her with my data and graphs, but it was a good exercise for me to explain why we decided to invest in stocks. Taking a look at your own investment makeup and figuring out if you can stomach large losses in the short to intermediate-term to reach your long-term goals is an important determination of your risk profile.

If you start at an early age you will have a long time to save until retirement. Use this exercise to determine how much variation in stock returns you can handle. If you can achieve your goals by saving more then go for it. Investing in stocks won’t be for everyone. You can sleep more soundly at night knowing you won’t experience huge losses.

Stocks don’t make sense for every investor so you need to match up your personal risk profile with your time horizon. Looking back on how different investments have performed historically can give you a better sense of how you would have handled those situations in the past. The returns will be different depending on where we are in the investment cycle. But it’s still a good exercise to look at what has happened in the past because as the famous saying goes, history doesn’t necessarily repeat itself, but it often rhymes.

[…] You can think of this as a way to increase the yield on your savings account and or even as a bond fund substitute. The 10 year treasury is currently yielding about 1.70%. This could be a solid strategy for someone that has a low tolerance for risk and is concerned about investing in stocks. […]

Hi,

very insightful article, thank you.

I definitely agree with you about the fact that stocks are the best way

to “keep” money sound & safe, growing, and out from the evil daemon of inflation.

I’m 29 and I want to start to invest in stocks. I have the luck of being able

to invest about 50.000$ per year, and only recently I have realized that

stocks are the best place where to invest to. (Too late! I have missed the “train”

of 2009 discounts)

Now, the only problem is *how* to invest in stocks 🙂

I mean: I’m a value investor, I’m learning how to recognize very valuable firms,

and I do fundamental analisys on securities.

When I found something good, how I can actually put money on the stock?

Do I have to wait that the prices plunge, and do a massive buy, or its better to use the Dollar Cost Averaging strategy? http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dollar_cost_averaging

Now that markets prices are very high, (overvalued?) would be better to wait

a possible plunge of prices and buy? (and, using DCA?) Or we can just starting buy with DCA? I’m very doubtful on this, thinking about these things all day long 🙂

A friend of mine told me that when Fed will stop the Quantitative Easing, which is in fact injecting big quantity of new money in the economy, the prices will plunge, returning back to a more “real” value. What you think about this?

I’m curious to hear your opinions in this very subjects. I think they’re very

important for beginners investors, and maybe can be the track for an entire

new blog post! 🙂

Many of them realized and understand how powerful stocks are over other

investments, but they don’t actually know how to *enter* into the market.

Thank you.

The fact that you are only 29 means that you have a very long time horizon until retirement (20, 30 or even 40 years depending on your plans). That means you shouldn’t worry about what the Fed will be doing to make your investment decisions.

DCA is probably the best way for the majority of investors to make contributions over time. Pick a period (bi-weekly, monthly, quarterly, etc.) and put your money to work over time. It’s the best way to control your behavior so you don’t have to try to time the markets to try an pick the “best” entry point.

No one can forecast the markets over the short-term, so it’s best to stay out of that game and focus on saving and thinking long-term. That’s for the overall market.

If you’re focusing on individual companies, there will always be some that will be undervalued in relation to their future prospects. Just make sure you have a process that you will follow over time that gives you some rules to help make your decisions so you’re not just guessing when the right time to invest is.

It has paid to have a long bias historically in stocks. This is especially true when you are young and can ride out the periodic losses that we will face from time to time. Keep your head down and keep making contributions.