Last year I wrote about the worst 10 year returns earned on a simple 50/50 portfolio of stocks and bonds. A reader recently dug up that post and asked for some further information and a look at different scenarios on the returns of a 50/50 portfolio made up of the S&P 500 and long-term U.S. treasury bonds.

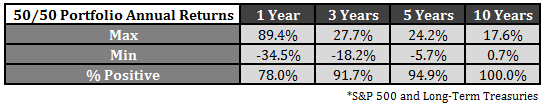

Using Ibbotson data, I went back to 1926 and looked at rolling monthly returns* to calculate various annual 1, 3, 5, and 10 year performance numbers using an annual rebalance for this 50/50 portfolio. Here are the relevant stats:

It’s nice to know that there’s never been a negative ten year return using a 50/50 portfolio, but the worst decade long stretch was barely positive with annual returns of less than 1% per year or a total return of just under 7%. This occurred during a ten year period ending in 1939 when the stock market was down 6.1% per year. Bonds provided a nice diversification benefit by rising 5.5% annually (overall returns were positive from the rebalancing bonus).

Every single one of the worst returns for this portfolio took place in the 1930s. The stock market was the main culprit for the poor performance. Stocks were down nearly 70% over a 12 month span in 1931-32 while bonds were slightly positive. In the worst three year result, also ending in 1932, stocks showed a -43.7% annual return while bonds were up 4.4% per year. The -5.7% five year annual portfolio return in the early 1930s came when stocks were down 18% per year with bonds picking up the slack up 3.5% annually.

The nightmare scenario we’ve touched on in the past concerns low stock and bond returns concurrently. This happened in the late-1960s and early 1970s as a ten year period ending in 1974 saw stocks return just 0.5% per year and bonds eked out a 1.3% annual return. This led to a 50/50 portfolio return of 1.3% per year (again the majority of which came from the rebalancing bonus). Of course, this was at the bottom of a nasty bear market, but it’s not out of the realm of possibilities to expect low stock and bond returns from today’s levels.

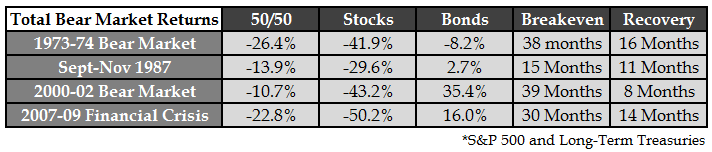

Since the majority of the worst performing periods clustered around the Great Depression, I decided to see how this 50/50 portfolio held up in some of the more recent bear markets:

These returns are all calculated using monthly returns, so they don’t give an exact daily peak-to-trough, but it gets you close enough to see the damage that can be inflicted by the markets. The breakeven column shows the number of months it took to make a round trip to get back to the prior peak level. The recovery column shows how long it would have taken from the bottom of the bear market to get back to the original breakeven level. The longest an investor in a 50/50 portfolio would have had to wait in these four scenarios to recoup all of their losses was just over 3 years in the bear market of the early 2000s. Patience, as they say, is a virtue.

The scenario I found most interesting is that long-term bonds were down in the 1973-74 bear market along with stocks. Rising interest rates trumped the usual rush to safety in bonds in this instance. I’ve said this before, but it bears repeating — investors would absolutely flip out if we were to experience a period of negative stock and bonds returns at the same time.

A few other takeaways:

- Investors should never expect to earn “average” returns in any given year or decade. Expect a wide range of results over time and never be surprised when you’re surprised.

- A simple diversified portfolio split evenly between stocks and bonds, rebalanced annually has produced pretty amazing returns over the past 90 years or so — close to 8% a year over this time frame. I’d be surprised if a simple mix of U.S. investment classes does the same over the next 90 years.

- Diversification outside of U.S. stocks and bonds always makes sense in my mind, but probably more so over the next decade. Could you have decent performance in a U.S.-only portfolio of stocks and bonds? Sure. But it’s a risk to assume you’re fully diversified by investing in a single geographic region, stock market capitalization or bond duration.

- A bond market “crash” is not the same thing as a stock market crash. The worst one year return in the S&P 500 was a loss of nearly 70% (again in the 1930s). The worst one year return in long-term bonds was a loss of 17% (in the early 1980s). Remember this when people say we’re in a bond bubble. Stocks crash; high quality bonds fall.

Further Reading:

What’s the Worst 10 Year Return From a 50/50 Stock/Bond Portfolio?

The Real Risk to a 60/40 Portfolio

An Alternative to the 60/40 Portfolio

Here were my favorite reads this week:

- Assume every investment can fail you (Monevator)

- 8 Things I’m Getting Too Old to Tolerate (Turney Duff)

- A closer look at investor Ed Borgato’s process (Richard Chignell)

- Google’s HR Manager: “Honestly, work just sucks for too many people.” (WSJ)

- Is long-term investing too popular? (Clear Eyes Investing)

- Tearing down the wall on annuities (Malice For All)

- The last thing I would want to do (Total Return Investor)

- Want to avoid a bear market? (Irrelevant Investor)

- Markets change and it’s always different this time (Morgan Housel)

- Important point on risk management: Confusing today’s liquidity with tomorrow’s (Reformed Broker)

- Should we treat financial advisors more like doctors? (Prag Cap)

Sign up for email updates and my monthly newsletter by clicking here.

Follow me on Twitter: @awealthofcs

*Rolling monthly returns aren’t a perfect statistical method for calculating average market returns, but it does give us more periods to study from a risk perspective.

I’m curious as to why you used long term treasuries in this analysis, when most investors would likely own total bond or intermediate bonds. Also, it would be interesting to look at real returns which are really more important than nominal returns. Especially in the 1970s.

True. The historical data on long-term bonds on a monthly basis extends much further back than intermediate-term bonds. While there is more volatility in the long bond than 10 yr treasuries, the returns are more similar than most imagine over longer periods. I wish there was more detailed data on intermediate bonds but it mostly only goes back to the late 1970s and covers a mostly falling interest rate environment.

Yes, good point. Hence the advise, in general, not to own long term bond funds as you get more volatility with not much more return than intermediate bonds.

Yup, I don’t think it makes sense for most investors to have their bonds in long duration maturities. Too risky for the minor bump in yield.

The common premise never seems to vary from the investor’s or anlayst’s point of view: that the S&P (stock) performance is the benchmark and maximum return against worst case drawdown is the holy grail. As a financial planner FIRST, I look at the Required Rate of Return as investment policy for a client, which is always middle single digit portfolio returns over a long time frame. If we are targeting the return (after taxes and inflation) which a client needs in order to secure a lifestyle for a lifetime – after all spending events – isn’t that a more sensible way to protect an investors capital? Our portfolios have, since 2008, generated on average between 6 – 7.5%, with commensurately reduced volatility. If a plan revealed a required ROR of 9-10% or better, I would tell the client we will have to start tweaking the lifestyle assumtions, especially with today’s forward looking expectations for lower equity returns and higher volatility.

It’s always been a problem for me that these portfolio returns analyses always assume that the investor is some universal prototype with the same all-in lifetime requirements and objectives as everybody else. How about measuring some historical portfolio terms against highest Sharpe Ratio as the holy grail, rather than highest average performance? Perhaps a 40/60 or 30/70 allocation might shine if they satisfy the required rates of returns revealed in the financial plans. It’s a wholly different paradigm, isn’t it?

Of course everyone’s situation and needs are different. This is more of a look at risk than returns. And I agree that risk-adjusted returns can matter, but you have to be careful with that bogie as well. See here:

https://awealthofcommonsense.com/risk-adjusted-returns-matter/

There’s no perfect one-size-fits-all solution. Historical returns provide perspective and context, not a forecast. It all comes down to the investor’s risk profile and time horizon, as always.

I understand. I would just like to see those who take an academic approach to this kind of research start pointing out to the average investor (and financial advisor) that their situation IS unique and they may not need to take the kind of risk that a “traditional” 60/40 or 50/50 portfolio inherently holds. The institutional approach is completely divorced from the realities of individuals approaching or in the time when their earnings-based lifestyle is shifting or has shifted to an asset-based one.

BTW, I really enjoy your writing!

Good point. It’s a completely different mindset when you have to use your portfolio for spending purposes. Thanks for reading.

I don’t know how every investor’s needs will be middle single digit returns. My experience has been that some do not save enough and need higher returns. And I know people who are 80 years old, are still working, have almost $30 million in savings and need zero returns to maintain their lifestyles. Am I missing something?

That is precisely my point. Individual investors are different from one another. Institutional investors rely on the generalized research that Ben has put forth in his article.individual investor tries to apply a institutional analysis to his or her personal situation, and it just doesn’t work. Financial planning is the basis for successful investing for the not so rich individual…IMHO.

Ok. I read your comment as “always middle single digit portfolio returns” was what you were saying investors always need.

Thanks for the opportunity to clarify that.

The problem with buying long bonds today is that it is like picking up nickels in front of a steamroller. Those paltry real returns are going to get wiped out in a hurry by a rise in inflation and/or rates.

Agreed. inflation has the potential to be the biggest part of that steamroller. See here:

https://awealthofcommonsense.com/kind-returns-can-long-term-treasury-investors-expect/

It’s generally okay to look at past returns to get some sort of handle on what to expect going forward. And this certainly is not a criticism whatsoever of this post. But what I so often see is advisors showing novice or even semi-knowledgeable investors returns over the last 5, 10 or even 20 years on bond funds or even balanced funds leading these investors to believe those returns are likely to be achieved going forward. The odds of bonds performing as well as they have in those past timeframes going forward is about as low and maybe even lower than the chance of winning the lottery. Precisely why the financial services industry has a bad reputation. (And advisors are not alone in doing this. Fund companies are as well).

Agreed. There are going to be a lot of investors caught off guard by bond returns from today’s levels. I covered this here:

https://awealthofcommonsense.com/back-testing-tony-robbins-weather-portfolio/

Lowering expectations is the only prudent move.

Thanks. I write investment stuff myself and have no idea how you can write and supply the amount of information that you do. The volume you manage to produce would be more than a full time job for me. Well done and greatly appreciated.

Thank you. I’ll keep writing as long as I keep finding interesting subjects to write about.

[…] A historical look at a 50/50 equity/bond portfolio. (awealthofcommonsense) […]

Thank you for yet another interesting article.

Do you have the maximum drawdown over any period for the 50/50 and 75/25 strategies (not just month end)?