Most investors spend their time worrying about the stock market, but the bond market is in a fascinating place right now. Interest rates are low, but retirees and risk averse investors need sources of income and a less volatile ride than the stock market provides.Everyone seems to want rates to rise, but it’s just not happening. Talking to a number of different investors over the past few months has led to a realization — nobody has a clue about what to do about bonds.

There are many different strategies and income-producing assets out there, but nothing’s perfect. Some stick with high quality government bonds regardless of the level of rates. Others are happy to look for higher yields elsewhere, further out on the risk curve. There are a number of ways to add income exposure to a portfolio, but yield is only the starting point. Risks must be considered as well.

Here are a few options, sorted by risk:

Interest Rate Risk.

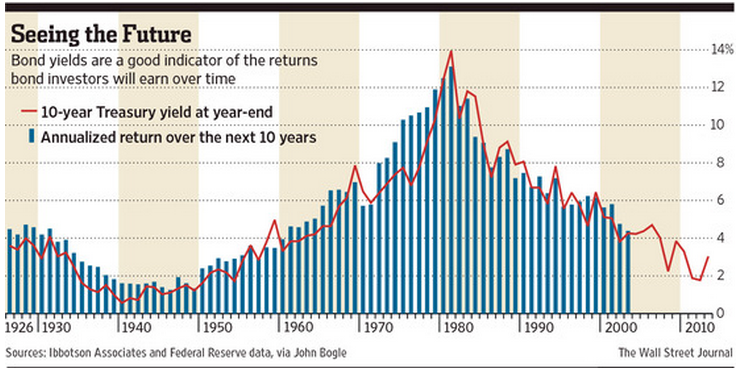

This is the biggest worry for bond investors right now, especially those holding high quality government issues such as treasuries. The correlation between current interest rates and future long-term returns is very high (around 0.90). This means lower performance can be expected in high quality bonds at these interest rate levels, something everyone has heard by now.

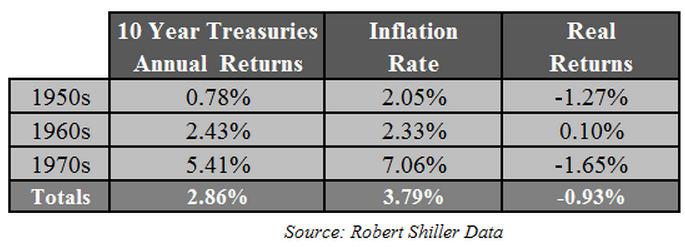

Inflation Risk. Inflation is the biggest risk to lower interest rates, as I’ve detailed in the past. There’s much less room for error. The historical record of bonds in rising interest rate and highly inflationary environment isn’t pretty:

It doesn’t look like much, but over 30 years that’s nearly a 40% loss in terms of purchasing power because of the effects of inflation.

Duration Risk. To combat interest rate risk and inflation risk, investors can choose to either lengthen or shorten the maturities of their bond holdings. Each option comes with potential problems.

Using longer bond maturities can increase your yield but also increases your chances of getting slaughtered in a rising rate environment. Higher rates and longer maturities are at higher risk of volatility and losses in a rising rate environment.

Or you could stick to the short end of marturities to decrease the effect of rising rates based on the theory that you could rollover your short-term bonds into longer-term holdings if and when rates ever rise in a material way. The risk here is that you could lose out on total return from lower yields. Many investors have been waiting for a number of years now in short duration bonds, anticipating a rising rate environment that just hasn’t materialized.

As usual, trade offs abound.

Sovereign Risk. Emerging market bonds offer higher interest rates, but they come with potential country-specific risks. Bond investors are usually more concerned with return of capital than return on capital.

Emerging market countries are no strangers to a crisis, but even when a minor flare-up occurs, there can be issues. In 2013, EM bonds were down 8%, supposedly on worries of how the Federal Reserve’s policy decisions would affect many EM countries. They’ve basically made back the losses in 2014, but provide a much wilder ride than most developed country sovereign bonds.

Asset Risk. There are a host of higher yielding investments that many view as bond substitutes, but most fail in the one area high quality bonds usually shine — preserving capital during stock market losses.

When the S&P 500 was down almost 20% in the summer of 2011, these were the drawdowns for some of the various higher-yielding investment options (along with their corresponding ETF tickers):

- Dividend Stocks (SDY) -16%

- Preferred Stocks (PFF) -8%

- Convertibles (CWB) -15%

- Bank Loans (BKLN) -8%

- Master Limited Partnerships or MLPs (AMLP) -13%

- REITs (VNQ) -14%

- High Yield Bonds (JNK) -7%

Portfolio Risk. This is probably the most important one. Investors searching for income have to be willing to make certain trade-offs or sacrifices in a low rate world. Investors have to figure out the purpose of bonds or income streams in a portfolio. Every asset class or holding within a portfolio should have a reason for inclusion.

For bonds it could be:

- Reliable income?

- A higher yield?

- Performance over inflation?

- A shock absorber during a stock market crash?

- Diversification benefits?

Figure out this question and hopefully the fixed income portion of a portfolio becomes easier to define. I also think that creating a bond ladder is a straight forward way to manage risk in fixed income assets, as well.

But there really are no easy answers right now.

[…] over inflation? A shock absorber during a stock market crash? Diversification benefits? What's An Investor To Do About Bonds? – A Wealth of Common SenseA Wealth of Common Sense […]

It seems odd that buyers in the 1960s realized total returns higher than their initial yield, when rising yields into the 1970s were undermining bond prices. Likewise, one might have expected buyers in the 1980s to realize total returns much higher than the initial yields owing to capital gains as interest rates fell.

Ibbotson’s returns are based on holding an on-the-run 10-year note, with frequent rollovers. But I’m puzzled why cumulative capital gains and losses from rollovers, during holding periods with significant yield changes, failed to have more impact on total returns. Any ideas?

These returns are based on the constant maturity 10 year bond numbers, so that could be part of it.

Rates moved up very slowly in the 60s so there until the past few years of the decade so that could be part of the reasoning behind the returns.

Thanks, Ben. Just made my own version of the chart, using initial yields and subsequent total returns from Global Financial Data.

Overall, it’s similar to the WSJ chart, but with some significant differences in places. For instance, GFD indicates that a buyer on 12/31/1971 at 5.89% initial yield, would have earned a 3.61% total return by 12/31/1981, with the yield ending 1981 at 13.98%. Whereas WSJ’s chart shows both the initial yield and subsequent 10-year TR at just under 6% for 1971. Odd … and hard to believe.

Interesting…that is hard to believe. I suppose you could say that shows how scared investors were about inflation if they were dumping bonds at such a clip that the price return negated most of the income return. I would love to see those numbers if you don’t mind emailing them to me.

What to do depends on where you are in life and what you need from your portfolio.

If you are not near retirement, the answer is to have a balance portfolio and wait out the recession, or market crash. That has always worked before.

If you are at or near retirement, then the best course is to hold mostly or even exclusively dividend growth stocks. Stocks that maintained their dividends through the Great Recession. It also means, not being so focused on your portfolio value. In retirement the income is more important. If that is uninterrupted, the value of the stocks, at any particular time is secondary. That change tends to be difficult one for many people, but it is the best solution.

That’s true assuming that the yield on the dividend stocks covers your living expenses, but retirees could still have 20-30 years to grow their capital in retirement so they need to think in terms of total returns as well. It’s also possible that dividend stocks are very expensive right now:

http://finance.yahoo.com/news/meb-faber-waves-red-flag-040000485.html

The biggest risk then would be getting scared out of them if they start to underperform.

But I do agree with you that it all depends on where you are in your life-cycle.

[…] bond investors. “There really are no easy answers right now,” writes Ben Carlson on his blog, A Wealth of Common Sense. But, since people have a variety of reasons for investing in bonds or bond funds, he suggests […]

[…] Whats An Investor to do About Bonds […]

[…] There are few easy answers for bond investors at present. (A Wealth of Common Sense) […]

Re interest-rate risk: extend you time horizon.

Although most bond portfolios maintain a relatively stable duration over time and are thus implicitly or explicitly “duration targeted,” the distinctive nature of duration targeting (DT) is underappreciated. The authors’ theoretical DT model demonstrates that over multi-year horizons, annualized DT returns converge back to the starting yield, regardless of the rate path. For example, for almost all six-year holding periods since 1985, Barclays bond index returns have converged to within 1% of the starting yield.

http://www.cfapubs.org/doi/abs/10.2469/faj.v70.n1.5

Interesting. Thanks for sharing. I have some historical treasury market data I’m going to put out next week that will highlight something similar.

[…] What To Do About Bonds? from Ben Carlson […]

[…] What’s An Investor To Do About Bonds? – A Wealth of Common Sense […]

Useful article. I wonder what that first graph (yields as a predictor of nominal returns) would look like if it used real returns. Got such a version? Thanks.

That’s a really goos question. Not something I have on hand but I will look into it and see if I can produce something because I think it would be interesting too.

[…] week I looked at some of the options available to bond investors in a low rate world. I showed that subsequent returns over the next decade tend to track the […]

dragon city hack tool

https://bft.usu.edu/s8qbm

[…] invalidate Robbins’ strategy. His numbers are still valid, but it would be a mistake to assume future returns in bonds will be anywhere close to where they were from […]

[…] What’s an Investor to do About Bonds? from Ben Carlson from A Wealth of Common Sense […]

[…] Reading: What’s an investor to do about bonds? Looking beyond interest rate risk in bonds Back-testing the Tony Robbins All-Weather […]

[…] The starting yields for both intermediate and long bonds in 1976 were close to 8% and peaked at over 15% by 1981. The current yields are in the 2-3% range, which means there is a much smaller buffer from the income payments when interest rates do rise and prices fall. Bond investors always have to remember that the long-term returns will track their starting interest… […]

[…] Further Reading: Common Sense Thoughts on Stock Market Losses What’s An Investor to Do About Bonds? […]