The 10 year Treasury yield recently hit 4.8%, its highest level since the summer of 2007.

That’s higher than the dividend yield on all but 53 stocks in the S&P 500.

Just four stocks out of 30 in the Dow Jones Industrial Average yield more than the benchmark U.S. government bond.1

The dividend yield on the S&P 500 has been falling for years from a combination of rising valuations and the increased usage of share buybacks from corporations.

But even those lower-than-average dividend yields were enough to offer some competition to bond yields in recent years.

Not anymore.

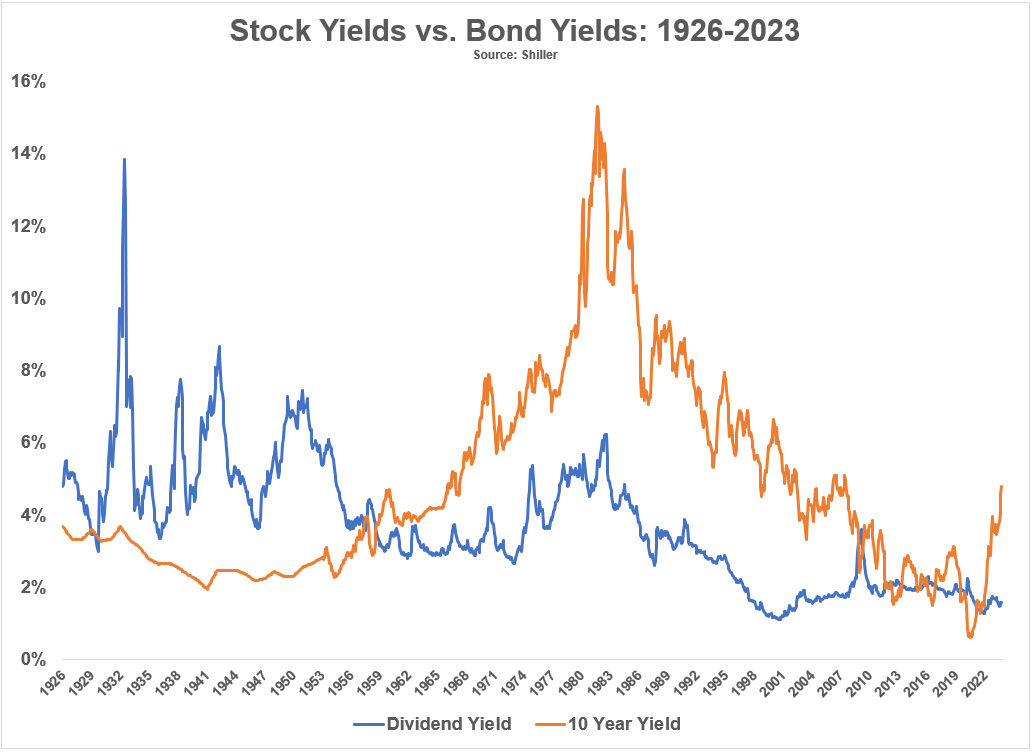

Here is the historical dividend yield on the S&P 500 compared to the 10 year Treasury yield going back to 1926:

In the early part of the 20th century, stocks actually yielded far more than bonds for decades. This was partly due to the crash in the Great Depression. It also had to do with the fact that there were fewer equity investors back then so corporations had to offer juicy dividend yields to attract buyers.

That relationship flipped during the 1950s bull market and the inflationary period that began in the 1960s. Stocks wouldn’t yield more than bonds again until a brief period at the bottom of the Great Financial Crisis in early 2009. There has been a back-and-forth ever since then.

Now bonds have a clear advantage.

Some people — myself included — wonder if higher bond yields mean trouble for the stock market. Higher yields are certainly welcome news for fixed income investors but it’s important to recognize the difference in yield characteristics between stocks and bonds.

Let’s say you’re a yield-focused investor who is thinking about locking in 4.8% in 10 year Treasuries for the next decade.

That’s $4,800 a year for a grand total of $48,000 in interest payments over the life of the bond.2

That’s pretty good especially when compared to the paltry yields of the past 15 years.

The S&P 500 dividend yield of 1.6% and $1,600 in annual income don’t come close to matching that.

But yields on the stock market don’t work the same as regular bond coupon payments. Dividend payments tend to rise over time.

Since 1926 dividends on the U.S. stock market have increased at an annual rate of 5% per year. And even though stock buybacks are an even greater part of the equation these days, dividends have grown even faster in modern economic times, rising 5.7% and 5.9% annually since 1950 and 1980, respectively.

Historically dividends are a wonderful inflation hedge as companies grow those payouts over time.

Let’s be conservative and assume the 5% annual dividend growth rate remains in effect. In 10 years your dividends jump from $1,600 to nearly $2,500. To match the 4.8% return on Treasuries you would need price growth of just 2.5% in the stock market over 10 years.3

That inflation-beating growth rate for stock market dividends doesn’t come for free though. Volatility is the obvious trade-off in this comparison.

My point here is we can’t simply look at the yields on stocks and bonds to make an informed investment decision.

Stock market yields and bond market yields are different animals with different risk characteristics. You must understand what you’re investing in and why before allocating to any asset class or strategy.

The good news is that the different nature of stocks and bonds makes them useful for diversification purposes.

Bonds provide regular income at preset intervals while stocks provide access to cash flows and earnings that have historically grown more than the inflation rate.

Inflation is a long-term risk for bond cash flows but stocks help protect you against the harmful impact of rising prices.

The stock market is unpredictable in the short-run while bonds tend to be more stable and boring (at least short-term bonds).

And if we want to take this a step further, cash equivalents like money markets or T-bills are a much better hedge than bonds in a rising interest rate/inflation rate environment. Cash is a terrible long-run inflation hedge but a wonderful volatility and interest rate hedge in the short-run.

Add it all up and a portfolio using some combination of stocks, bonds and cash provides a durable option using simple asset classes.

Diversification doesn’t work all the time but it works most of the time and that’s about as good as you can hope for in the markets.

One of the biggest reasons for this is the different features stocks, bonds and cash have in different economic and market environments.

Absent the ability to predict the future, a diversified portfolio that is durable enough to withstand a wide range of outcomes is still your best bet for long-term survival in the markets.

Further Reading:

Why Aren’t Investors Selling Stocks to Buy Bonds?

1Walgreens, 3M, Verizon and Dow Chemical.

2I’m leaving out the idea of reinvestment risk here as well, depending on what you do with that income.

3For 30 year bonds the math is even more in your favor for stocks. After 30 years of 5% growth in dividends, you would be earning more than $6,500 annually in the stock market.