Whenever there is an extreme move in the economy or markets most people want a simple explanation.

We want a single variable to explain what just happened.

Interest rates rose because of X.

We went into a recession because of Y.

Stocks crashed because of Z.

But when it comes to something as complicated as the economy or markets, it’s never just one variable. It’s usually a bunch of things.

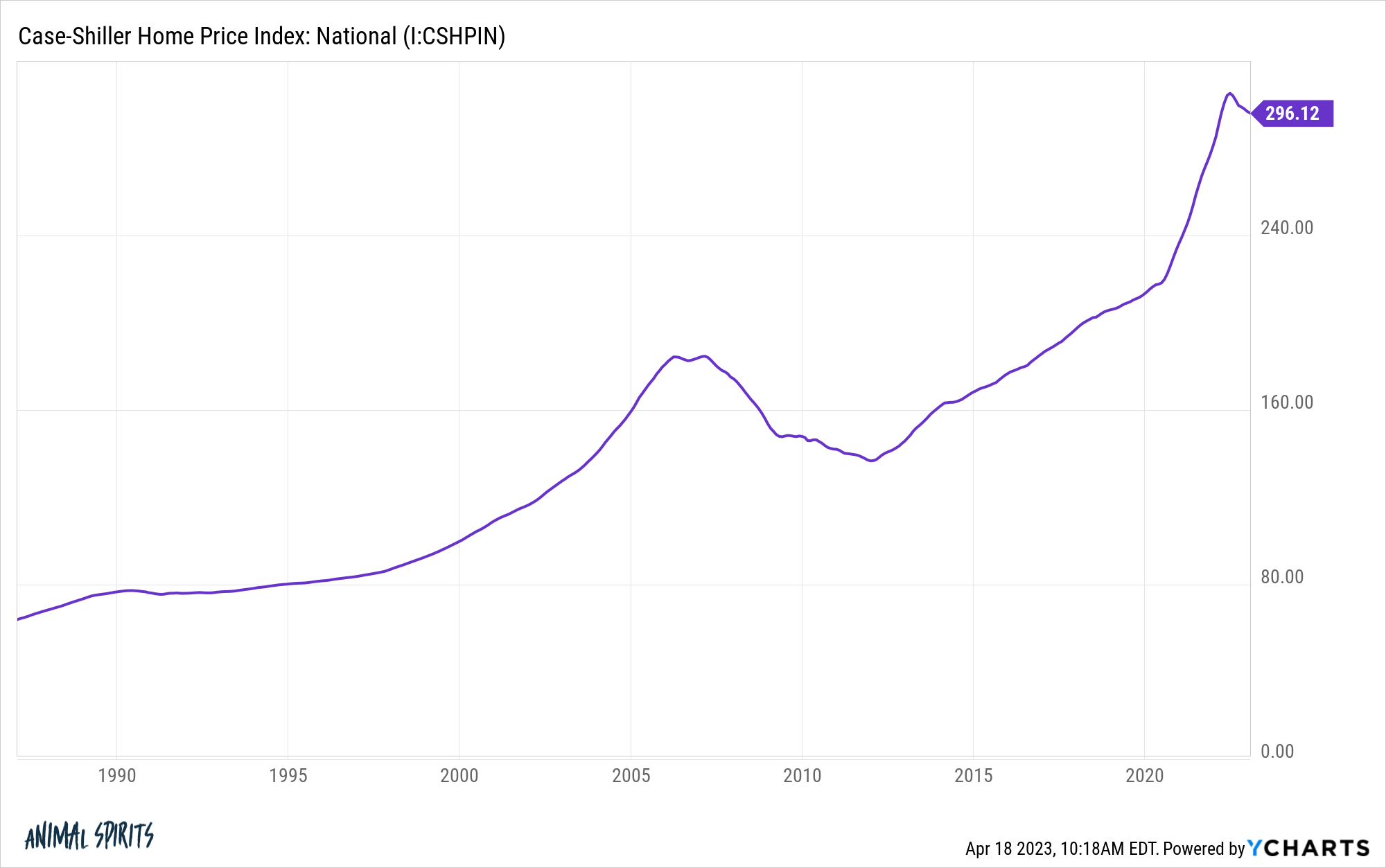

Take the housing price gains we’ve seen since the onset of the pandemic in early-2020. You can clearly see prices detach from the long-run trend:

There are a number of reasons for this unprecedented move.

Mortgage rates went to generationally low levels.

People got bored with their living situation from being inside all of the time and not doing anything.

Young people who were going to buy a house at some point got the itch now that they had more time to search for houses.

And millions of people now had the ability to work remotely.

According to research from the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco, that last one was one of the key contributing factors. They estimated more than 60% of the pandemic-related gains were from the move to remote work.

I’m not sure about the precise attribution weights here but this seems directionally right to me. The ability to work from anywhere opened up all kinds of new housing markets for people and made the home even more important since it would now double as an office for so many workers.

But if so many people moved from California and New York to Boise and Nashville, why did housing prices and rents actually increase in so many of the big cities during this time as well?

If people finally had the ability to move from higher cost-of-living areas why did the cost of living continue to rise in those cities?

Adam Ozimek and Eric Carlson have a new research paper that answers this question.

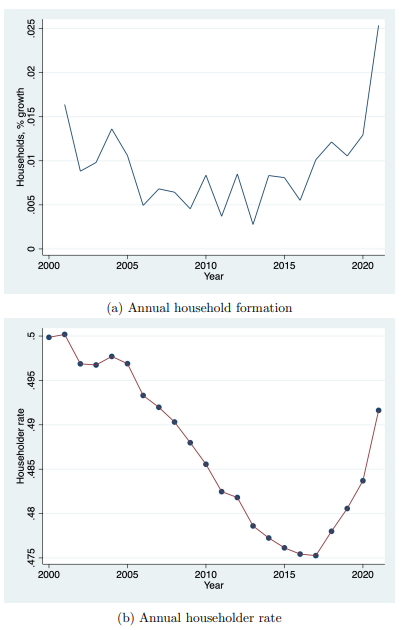

The countervailing force here was household formation:

People who had roommates decided to rent their own place. Millennials who lived in their parent’s basement moved out.

Household formation more than made up for any population declines or stagnation in big cities.

You can see those trends were already in place before the pandemic since millennials are now the biggest demographic in the United States. But the pandemic supercharged the trend because people mostly kept their jobs, repaired their balance sheets, saved some money and finally decided to buy a house or rent an apartment for themselves.

The demographic wave of millennials in their household formation years more than made up for the remote work phenomenon.

You could argue this same demographic wave of household formation is making it more difficult for housing prices to fall substantially.

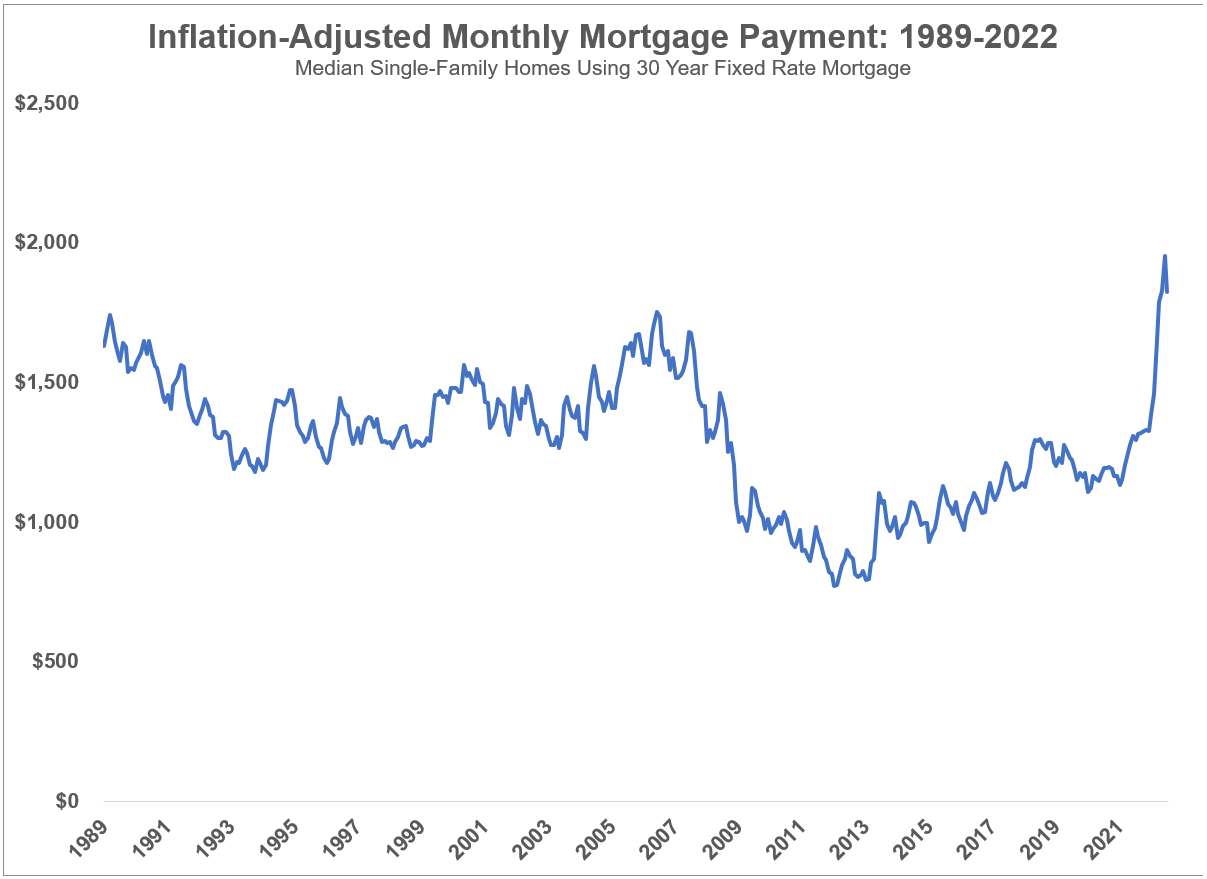

On the surface, one would assume 6-7% mortgage rates combined with a 50% surge in housing prices in a few short years would lead to a substantial re-rating of housing prices to the downside. The math on housing affordability presents a pretty clear-cut case for much lower housing prices:

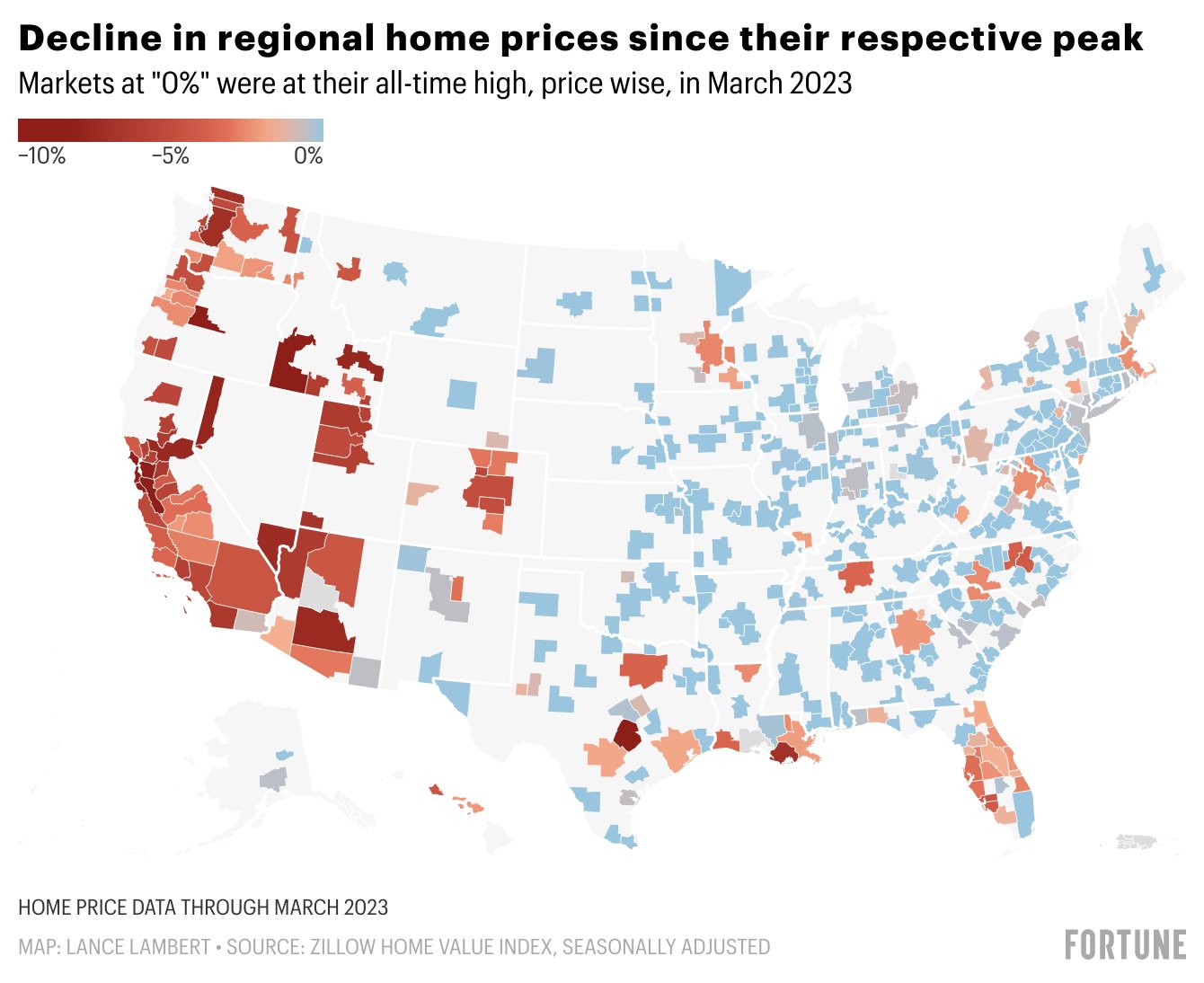

And it is true that housing prices are falling in certain areas. But prices are stubbornly resilient in much of the country.

Lance Lambert created this slick chart that shows home prices versus their all-time highs across the country:

He notes that 55% of the 400 biggest housing markets in the country are either back to new all-time high price points or close to it.

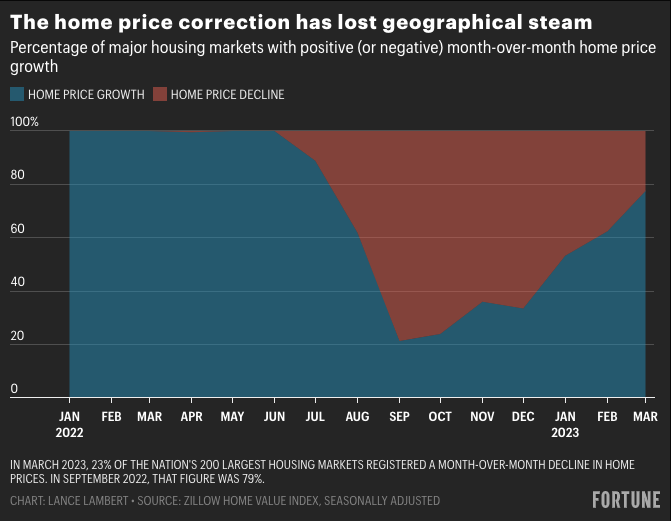

The home price correction was gaining steam and now it’s reversing:

There is no blood in the streets just yet.

Here is a snapshot of the current housing market:

- Prices are about as unaffordable as they’ve ever been from a monthly payment perspective.

- Housing supply remains constrained because so few people want to move out of their 3% mortgage or buy into a new 7% mortgage.

- Because supply is so constrained and so many millennials want to buy a house, demand exceeds supply.

- So prices should be falling more but the demographics of household formation are essentially putting a floor under prices.

This environment can’t last forever. Eventually, people will start to move or rates will come down and inventory will pick up again (I hope). Or if rates stay at 6% or 7%, you would expect prices to slowly grind lower.

But household formation and demographics are a big reason why housing prices aren’t falling as much as some people would like.

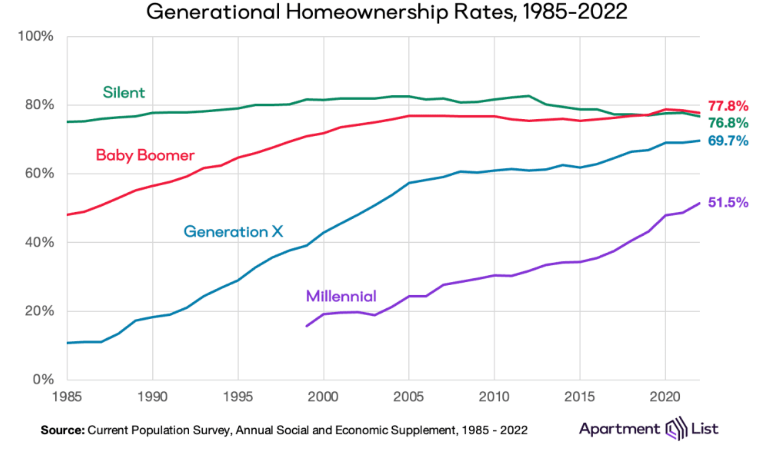

Millennials still have some work to do when it comes to catching up to other generations in terms of homeownership:

I’m not willing to bet against this trend.

Further Reading:

Demographics Are Destiny in the Housing Market