I did an interview with Janet Alvarez for The Business Briefing on SiriusXM last week and she asked me for something I’m thinking about that not a lot of investors are talking about at the moment.

It’s kind of hard to find something no one is talking about because so many people are talking all the time now what with 24-hour financial news channels, a plethora of financial media companies, blogs, Substacks, newsletters, social media and so forth.

Having said that, my sense is so many investors are still licking their wounds from the worst year ever for bonds in 2022 that not enough people are paying attention to the much higher yields you can earn in short-term U.S. government debt right now.

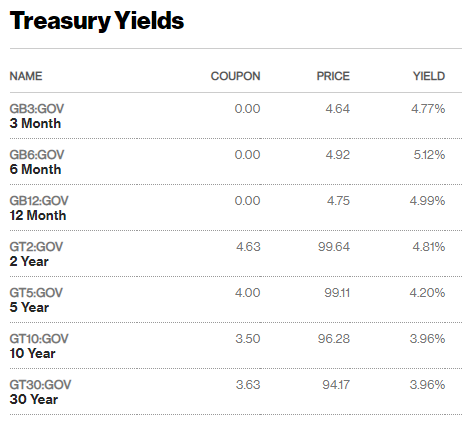

Just look at the yields on everything 2 years and under:

We’re talking 5% for 6 and 12-month T-bills and darn near close to that for 3-month T-Bills and 2 years treasuries. And it’s not just that these yields are about as high as they’ve been this entire century; it’s how high they are relative to longer-term bond yields and their own history.

Ten year treasury yields are certainly higher than they were during the initial stages of the pandemic but still low compared to historical averages.

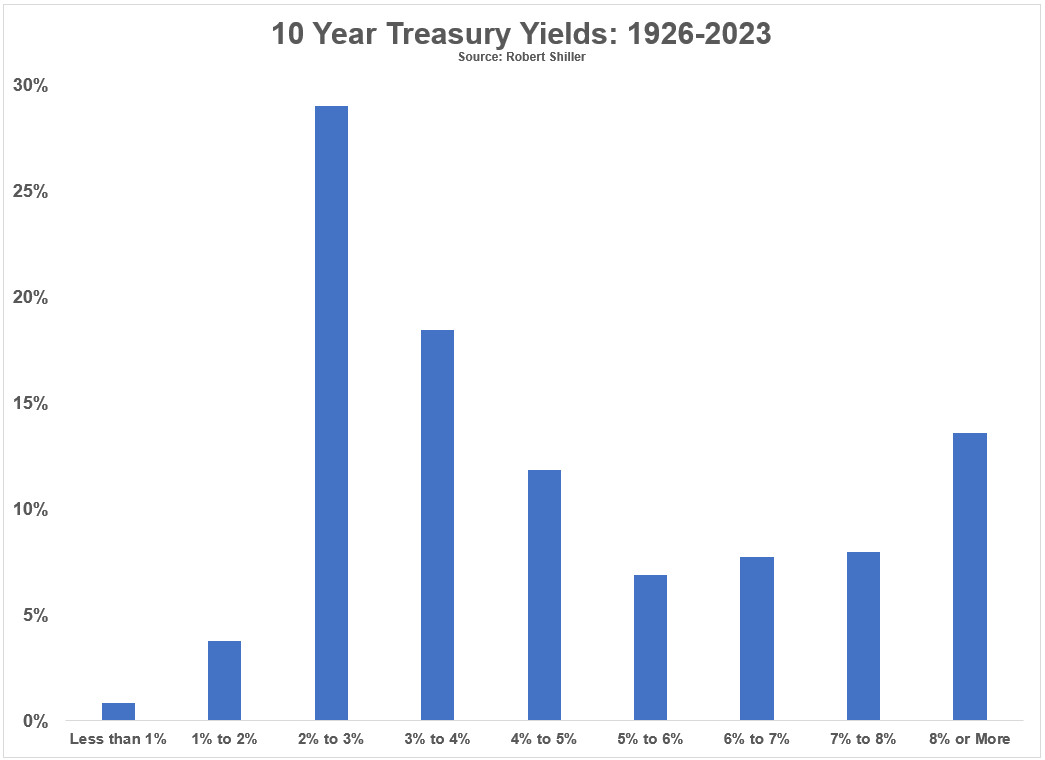

Here is the distribution of 10 year yields going back to 1926:

The average yield over this time frame is 4.8% so the 10 year yield is still below average. Roughly two-thirds of the time yields have been 3% or more while 60% of the time they have fallen in the range of 2-5%.

T-bill rates, on the other hand, are higher than average at the moment.

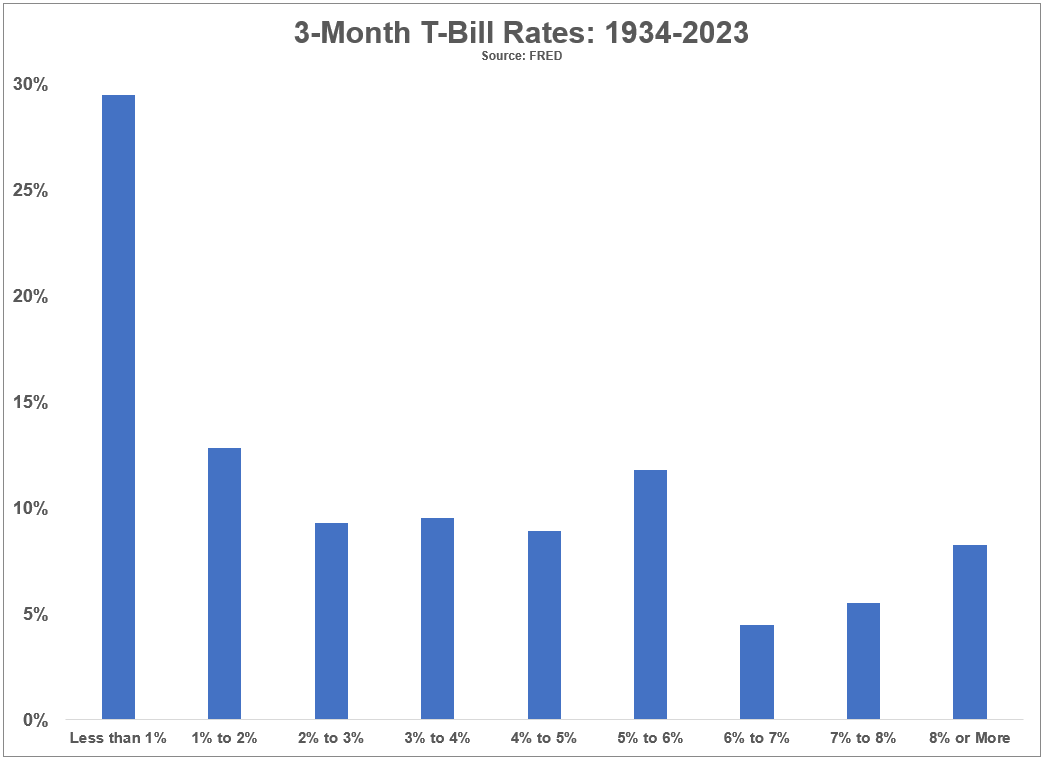

I have data for 3-month T-bill rates going back to 1934:

The average rate since 1934 is 3.4%. The current yield of around 5% has only been in place 30% of the time. So 70% of the time yields on short-term government paper, a good proxy for CDs, savings accounts and money markets, have been less than 5% over the past 90 years or so.

Because of the Fed’s interest rate hikes, investors are being offered a gift right now in the form of relatively high yields on essentially risk-free securities (if such a thing exists). You don’t have to go further out on the risk curve to find yield right now.

Short-term bonds with little-to-no interest rate or duration risk are offering 5% yields.1

The big question for asset allocators is this: Will higher risk-free rates impact the demand for stocks and other risk assets which leads to poor returns?

This makes sense in theory. Why take more risk when that 5% guaranteed yield is sitting there for the taking?

The relationship between risk-free rates and stock market returns is not as sound as it would seem in theory.

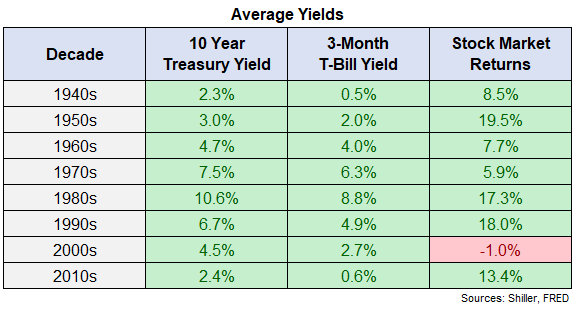

Here are the average 10 year treasury yields, 3-month T-bill yields and S&P 500 returns by decade going back to the 1940s:

The highest average yields occurred in the 1980s, which was also one of the best decades ever for stocks. Yields were similarly elevated in the 1970s and 1990s but one of those decades experienced subpar returns while the other saw lights-out performance.

Yield levels were more or less average in the 2000s but the stock market performed terribly.

I could have added inflation or starting valuations or economic growth or a bunch of other variables to this table. But maybe that’s the point — context is more important than interest rate levels alone.

I also looked at the performance of the stock market when 3-month T-bill yields averaged 5% for the entirety of a year (which could happen this year). That’s been the case in 25 of the last 89 years.

The annualized return for the S&P 500 in those 25 years was 11%. So in years with above-average risk-free rates, the stock market has actually seen above-average returns.

I’m not saying stocks are guaranteed to do well in a higher-rate environment. Maybe investors will be content with 5% yields this time around. But history shows they’re not guaranteed to do poorly simply because cash is offering higher yields.

It’s important to remember that stocks are long-duration assets while T-bills are not. Just as stocks can fluctuate in the short-run so too can the risk-free rate.

It could be that investors are in search of higher returns when risk-free yields are high because those periods tend to coincide with higher inflation.

Five percent sounds pretty great right now compared to yields of the past 10-15 years but some might scoff at those rates when inflation is still running at 6%.

Inflation will likely continue to matter more than interest rates since yields will follow the path of inflation from here.

The good news for investors is a hotter-than-expected economy is now offering better risk-free rates than we’ve seen in years.

The paradox here is it could require a slowdown in the economy to vanquish higher-than-average inflation. If that happens, risk-free rates are likely to fall as well.

Enjoy the high yields but don’t expect them to last forever.

Further Reading:

Inflation Matters More For the Stock Market Than Interest Rates