The U.S. inflation rate remains stubbornly high, clocking in at 8.3% for this week’s latest reading.

Many people think this gives the Fed even more ammunition to continue raising short-term interest rates from their current levels of around 2.5%. Rates could get as high as 4-5% before all is said and done.

Ray Dalio thinks this could be a bad thing for the stock market:

I estimate that a rise in rates from where they are to about 4.5 percent will produce about a 20 percent negative impact on equity prices (on average, though greater for longer duration assets and less for shorter duration ones) based on the present value discount effect and about a 10 percent negative impact from declining incomes.

This makes sense from a financial theory perspective. Any financial asset is simply the present value of future cash flows discounted back to the present. And the way you discount those cash flows is through interest rates.

Higher interest rates should, in theory, lead to a lower present value.

This not only makes sense in theory but in common sense terms as well. If your hurdle rate is higher, you’re going to require a lower starting price to make an investment worthwhile.

Dalio could be right. This is the first time in a long time government bond yields have offered investors rates that could make them stop and think about putting their cash to work in risk assets.

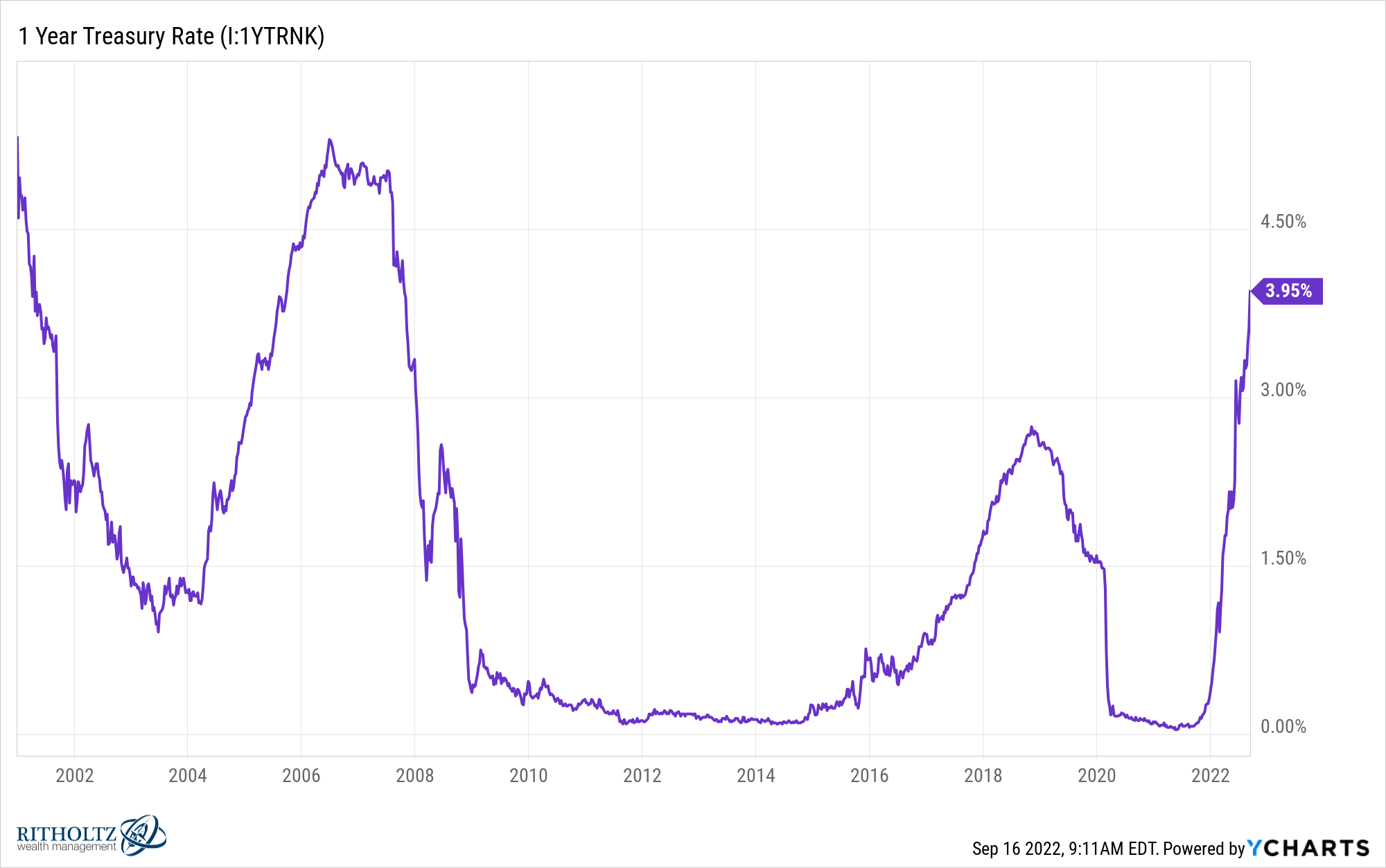

The one year treasury is now yielding 4%. Real yields remain negative since inflation is still so high but these are the highest nominal yields for short-term bonds since before the 2008 crash:

It’s not only the level of rates but the speed at which they are rising. The yield on one year treasuries just a year ago was 0.07%. It’s up almost 60x in a year.

So is the stock market screwed?

Maybe. Dalio’s logic makes sense.

But the stock market doesn’t always make sense, especially when it comes to interest rates.

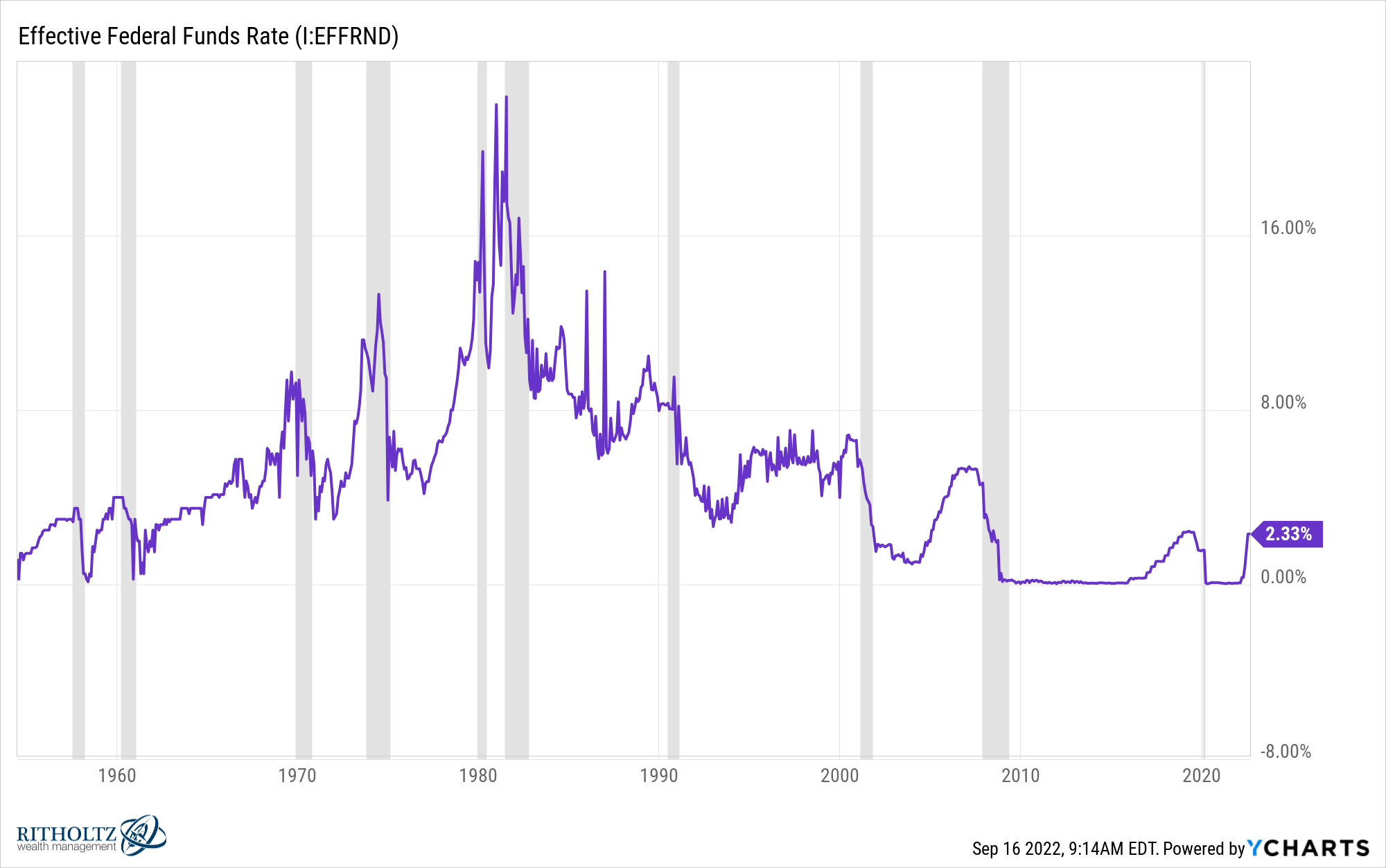

Here’s the Fed Funds rate going back to the mid-1950s:

Interest rates have been in secular decline since the early-1980s but the three-decade period before that was a secular rise in rates.

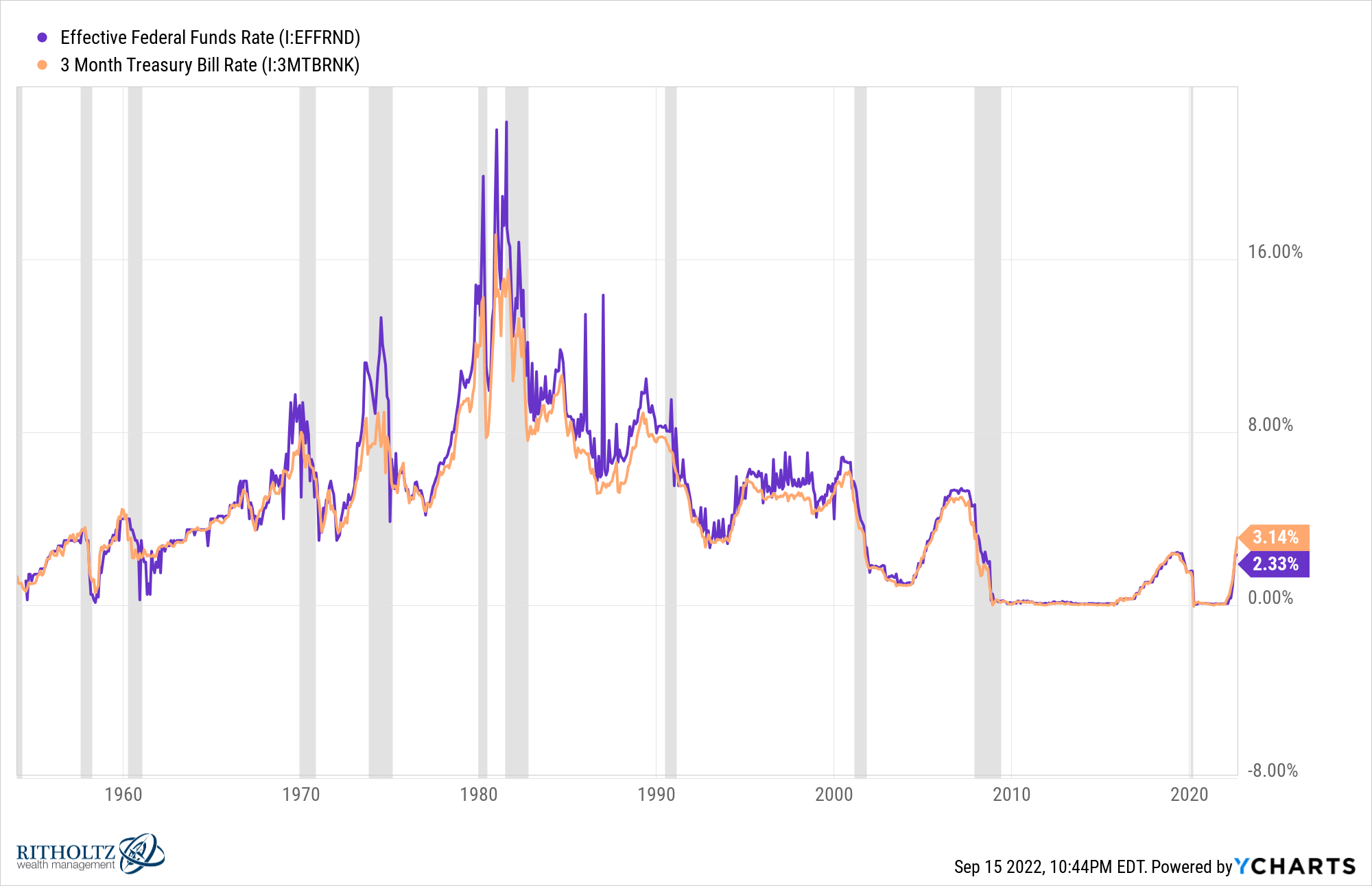

The 3-month T-bill is a pretty decent proxy for the Fed Funds Rate:

Since there are some movements in rates in-between meetings it’s easier to use these short-term treasury bills as a proxy for historical comparisons.

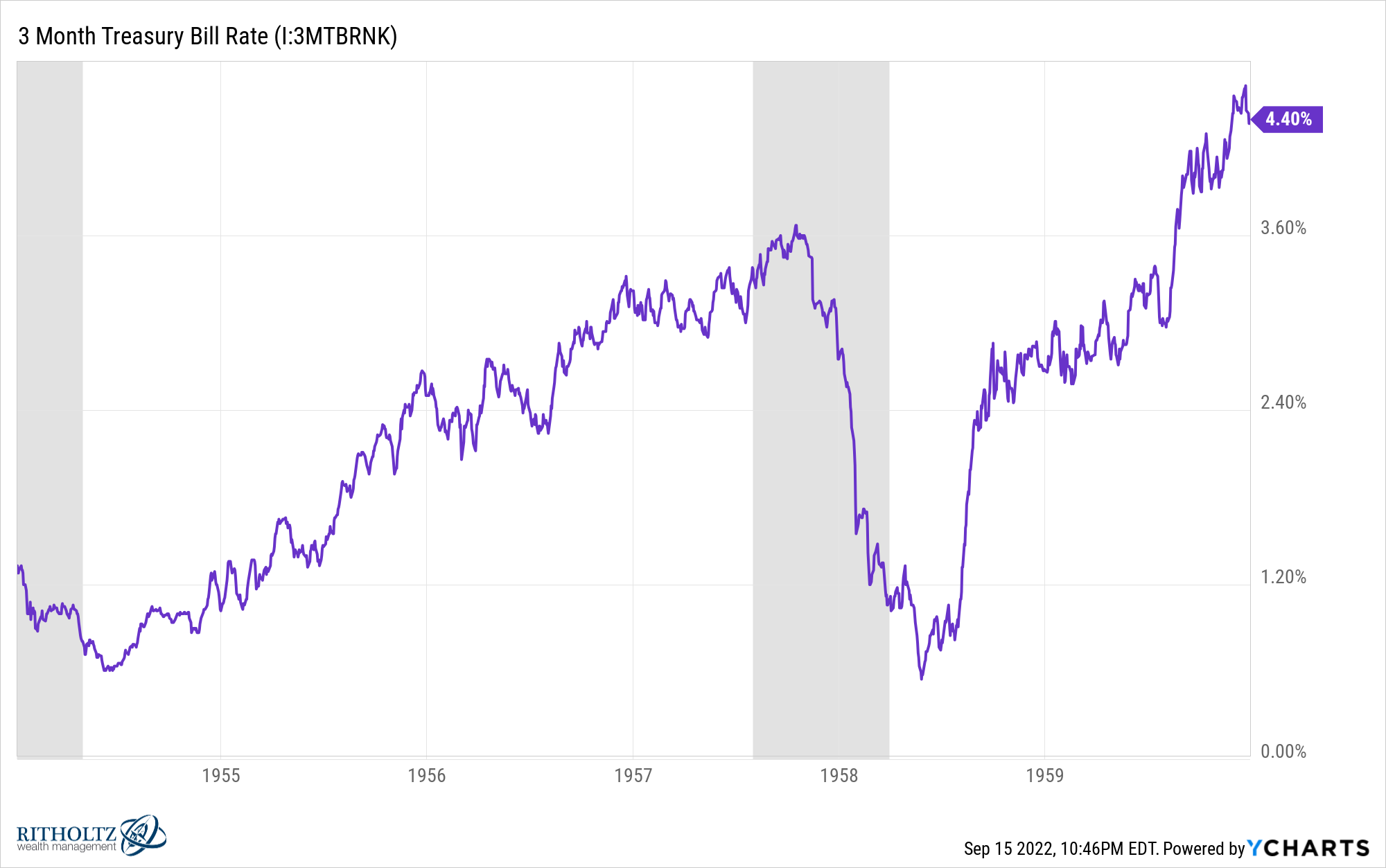

The 3-month T-bill was just over 1% in 1954 but ended the decade at more than 4%:

During this time frame, the S&P 500 was up 21% per year or more than 210% in total.

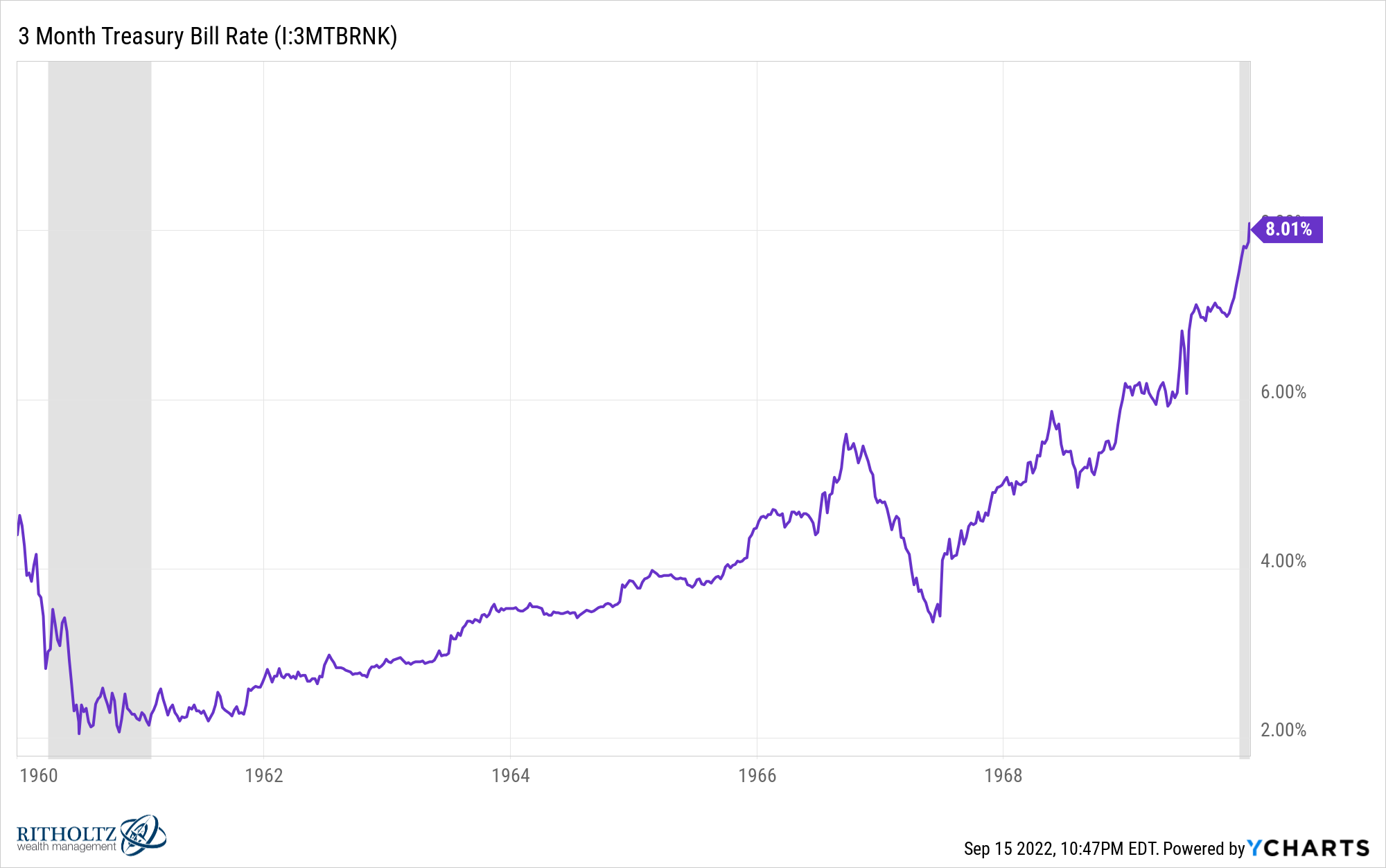

Short-term rates nearly doubled in the 1960s, going from a little more than 4% to 8%:

The 1960s weren’t a great decade for the stock market but the S&P 500 was up a respectable 7.7% annually. Close to 8% per year is not bad during a time when interest rates doubled.

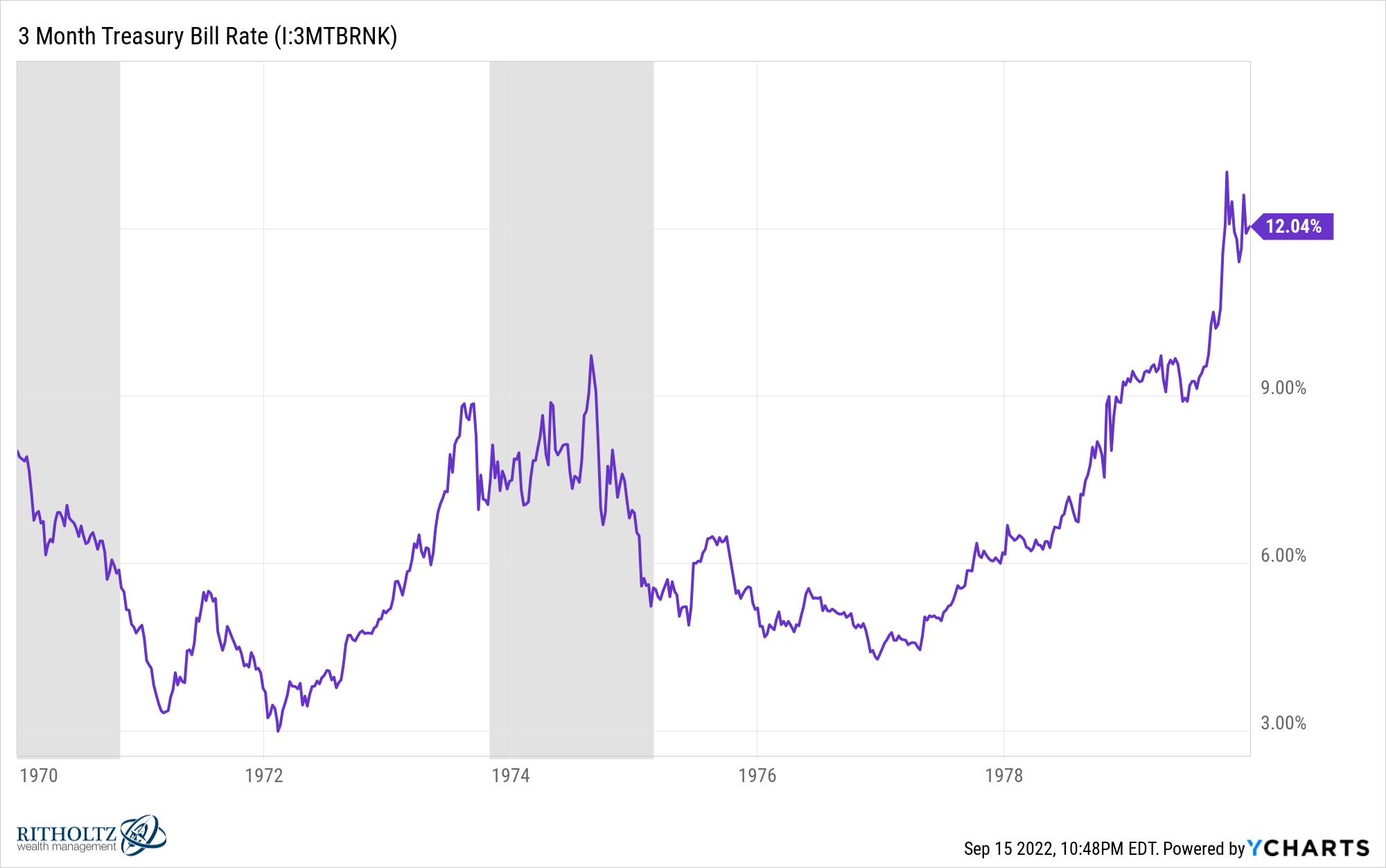

In the 1970s, short-term yields went from 8% to 12%:

Nominally the U.S. stock market did okay in the 1970s. Stocks were up 5.9% per year even as interest rates were breaking through double-digit levels.

The problem is inflation was 7.1% so stocks were down on a real basis.

And that’s the biggest difference between the 1950s, 1960s and 1970s. While inflation was more than 7% per year in the 70s, it was just 2.0% and 2.3%, respectively, in the 50s and 60s.

So while the real returns were spectacular in the 1950s and pretty good in the 1960s, they were awful in the 1970s.

You can never gauge the markets using any single variable but if I had to rank them in terms of importance, inflation would get more first place votes than interest rates.

I know a lot of people would like to believe falling interest rates were the sole cause of the entire bull market in stocks from the early-1980s but my contention would be disinflation was a bigger catalyst.

Does this mean Dalio will be proven wrong?

I don’t know. Maybe interest rates matter more right now because investors got used to them being so low for so long.

But the bigger risk to me isn’t rising rates, it’s high inflation sticking around a lot longer.

Michael and I talked about the impact of high hurdle rates on the stock market on this week’s live taping of Animal Spirits:

Subscribe to The Compound so you never miss an episode.

Further Reading:

Inflation Matters More For the Stock Market Than Interest Rates

1Read more here for some thoughts on why the stock market doesn’t like high inflation.