In 1928, economist Irving Fisher wrote a book called The Money Illusion that was all about inflation.1

The best way to view think about inflation back then was through the lens of wars and how they impacted the economy. Fisher lays out that relationship:

Usually inflation comes when governments are in financial straits, especially in war time, or after a war has crippled the government’s financial powers. War has always been by far the greatest expander of paper money and credit, and therefore the cause of the greatest price upheavals in history.

Basically, the way things played out in the late-19th and early-20th centuries went something like this:

- First, there would be a period of uncertainty during the war in terms of the outcome and which countries would be impacted the most.

- Next, there would be a post-war recovery from all of the government spending during the war.

- All of that spending would lead to an overheating of the economy, inflation and then a bust that would inevitably follow the boom.

- And after a post-war depression the economy would find its footing until the next war came along.

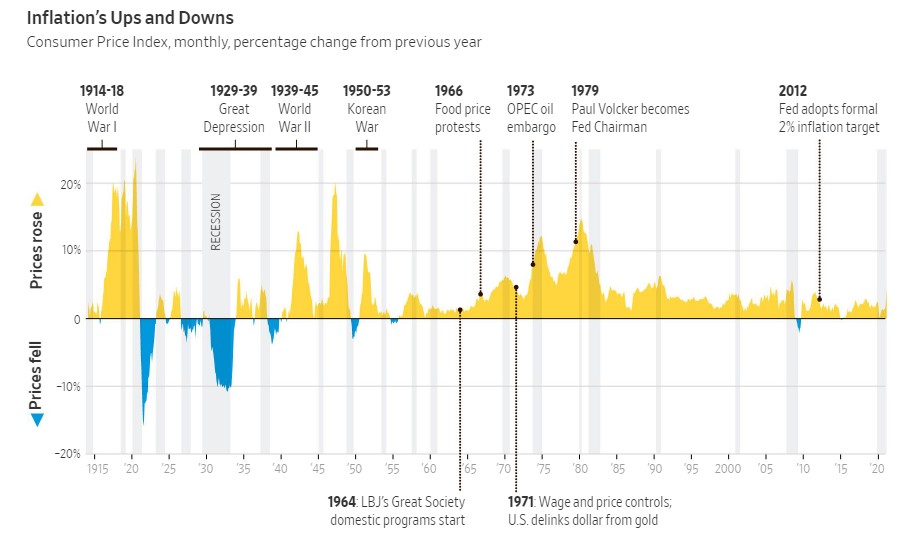

Jon Hilsenrath at the Wall Street Journal recently provided a historical look at inflation going back to World War I which does a nice job illustrating this idea:

The early-20th century is littered with enormous booms and busts from skyrocketing inflation to punishing deflation. Not only were the downturns magnified back then but they also occurred more often than they do today.

Aside from the inflationary 1970s period, the post-WWII era has been a much smoother ride from a price perspective than the pre-WWII era.

A more mature economy that isn’t subject to depressions and economic panics once every few years is a good thing. It also makes it much harder to predict economic output using historical relationships, especially when it comes to inflation.

Inflation just might be the hardest economic variable to forecast or understand in the U.S. economy.

I’ve read multiple books about the 1970s inflationary spike and I’m still not quite sure the exact reasoning for it. There are plenty of theories but no single satisfying narrative that helps explain what happened.

The Fed has been actively seeking a 2% inflation rate since the end of the Great Financial Crisis. Yet more than 63% of the time since 2010 the trailing 12-month inflation rate in the U.S. has been less than 2%. They printed more money than ever before and kept rates at 0% for years on end and yet inflation never really showed up.

The market isn’t great at predicting inflation either.

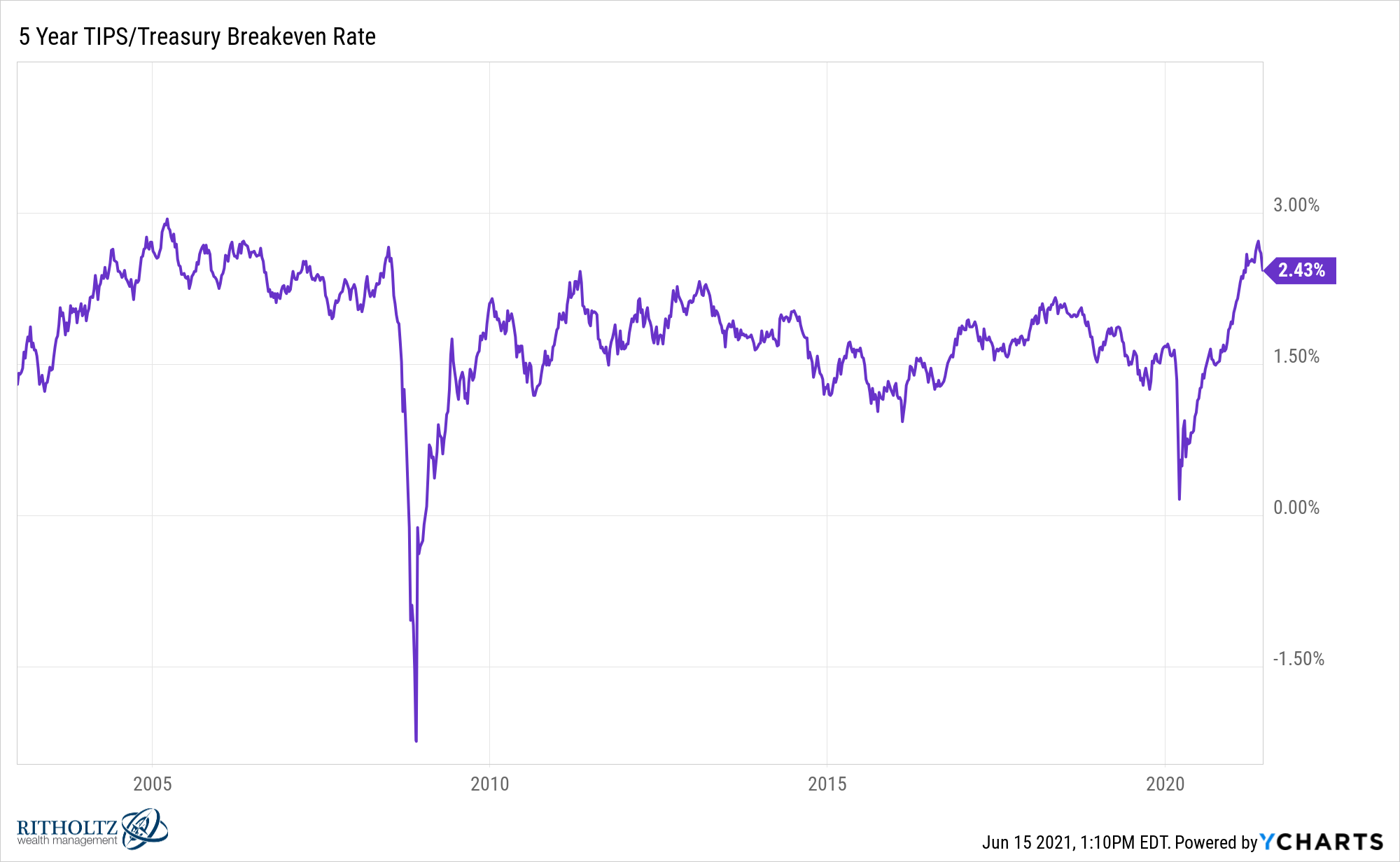

The breakeven rate shows the difference in yields between treasury inflation-protected bonds (TIPS) and regular treasury bonds, which is essentially the market’s prediction of the coming inflation rate:

This chart has had many people worried about higher inflation because that’s what the market has been pricing in. Unfortunately, this breakeven rate isn’t all that helpful when it comes to predicting actual inflation going forward.

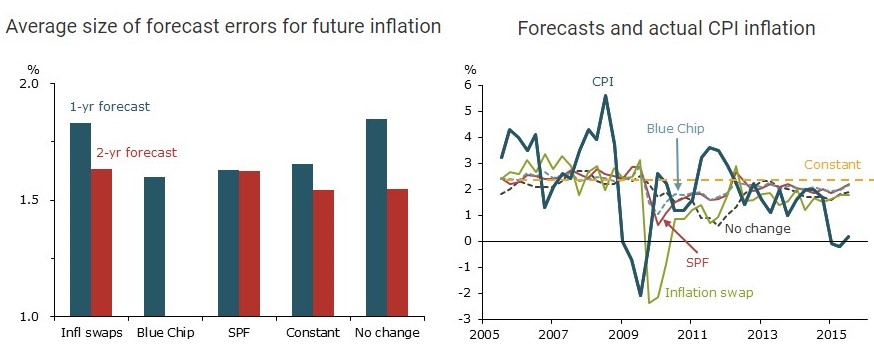

The San Francisco Fed produced a research report that looked at breakevens and a number of other inflation models to test their predictive power. The results weren’t great:

Surveys were actually a little better than market-related factors but you can see the average forecast errors were all at least 1.5%. When your target rate of inflation is 2% that’s a pretty decent margin of error.

The main argument at the moment about inflation is whether it’s finally here to stay from all of the government spending or simply transitory from a quirky pandemic economy. There are solid cases for both sides of this argument.

The reasons this bout of inflation could be transitory are as follows:

- We have all sorts of supply shortages from the pandemic as companies didn’t foresee demand coming back online this soon.

- People are ready to spend money now that things are opening up so there is a ton of pent-up demand in the system.

- Things will eventually get back to normal once some of the supply bottlenecks are figured out and people spend more money on experiences than goods.

- Demand will slow eventually once the extra unemployment benefits end and no more government checks are on the horizon.

- Demographics remain a headwind.

And the reasons inflation could remain elevated going forward:

- Millennials have an insatiable thirst for housing which could make some supply shortages stickier than they should be.

- Once you raise wages it’s going to be impossible to lower them back to previous levels (see Josh’s piece on this).

- Fiscal stimulus might be here to stay which could lead to a new higher level of demand than we’ve had in the past.

- Psychology plays a large role in driving inflationary pressures so it’s possible consumer and company reactions could lead to higher prices based on expectations for future higher prices.

I’m leaning towards the transitory but higher than the previous cycle camp but wouldn’t be surprised either way.

We’ve never conducted an economic experiment of this magnitude before. No one knows how all of these trillions of dollars are going to impact the trends that were underway before the pandemic when it comes to demographics, interest rates, prices, spending, supply and demand.

The psychological component is probably the hardest part of this endeavor. Changes to wages, prices and supply shocks can change people’s behavior in ways market models simply can’t predict.

One thing is for sure — the economy is far more interesting than the stock market right now.

Further Reading:

Never Go Full Weimar

Pandemics vs. Post-War Recoveries

1You may recognize Fisher from such ill-timed quotes as “Stock prices have reached what looks like a permanently high plateau,” in 1929 just before the Great Depression knocked more than 85% off the value of the market.