A podcast listener asks:

I was wondering if there is any logic to waiting until interest rates go higher to buy a home if you plan on putting down 50%-75% as a down payment? This would presumably give the house more upside potential to increase in value if rates go down and would be more of a buyer’s market. I would conservatively invest the down payment money and continue to rent in a city where housing prices have increased 20% in the past year, but rent has gone down slightly.

I understand the thinking here.

The housing market is scalding hot right now. The Case-Shiller U.S. National Home Price Index was up more than 11% year-over-year in January. Places like Phoenix (+15.8%), Seattle (14.3%) and San Diego (+14.2%) were up even more.

We’ve all heard anecdotes of houses selling the first day they get listed with multiple offers over asking. A combination of low rates, low supply, demographics and the pandemic has made things increasingly difficult on buyers.

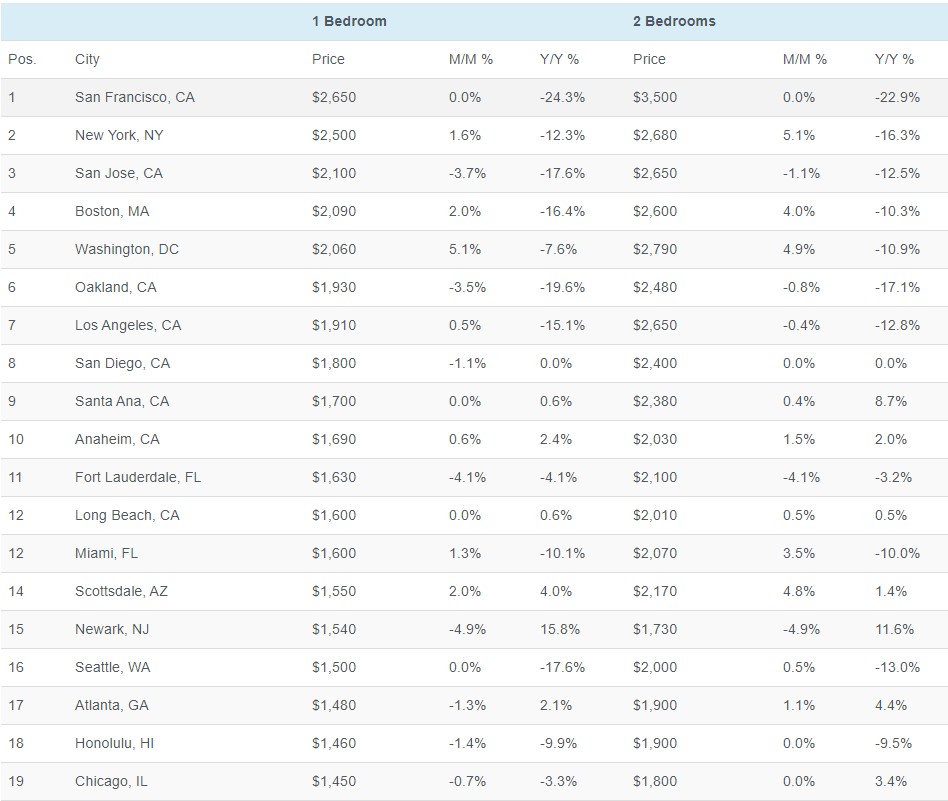

And when you juxtapose housing prices with rents you can see they’re going in different directions (data from Zumper):

Now is a great time to be a young person looking to rent in a big city. For first-time buyers on the other hand…not so great.

It may be tempting to try to time the housing market and buy the proverbial dip once things cool off a bit from rising supply, rising rates or demand cooling off once the pandemic is over.

But there are risks involved in waiting as well. Here’s another email from a podcast listener:

Hey guys, I need your help on how to get over a missed opportunity. I’m 26 years old and live with my mom. We live just outside Toronto, Canada. About 1.5 years ago I was looking at houses worth around $550k. At the time I thought they were expensive and I wasn’t yet ready to move out so I passed on it. I figured the only reason at that time I would be buying was to speculate on housing prices, my plan would have been to rent it out and then move into the house when I was ready to move out. Now I’m about ready to move out and these same homes are selling for $900k+. I can’t believe it. I have no idea what to do now. I also can’t stop thinking about real estate. I’ve never felt FOMO like this before. How can this market keep going higher?

The housing market can remain irrational longer than you can avoid FOMO. And although a place like Toronto is an outlier, there are no guarantees housing prices will fall just because you’re nervous prices are too high right now.

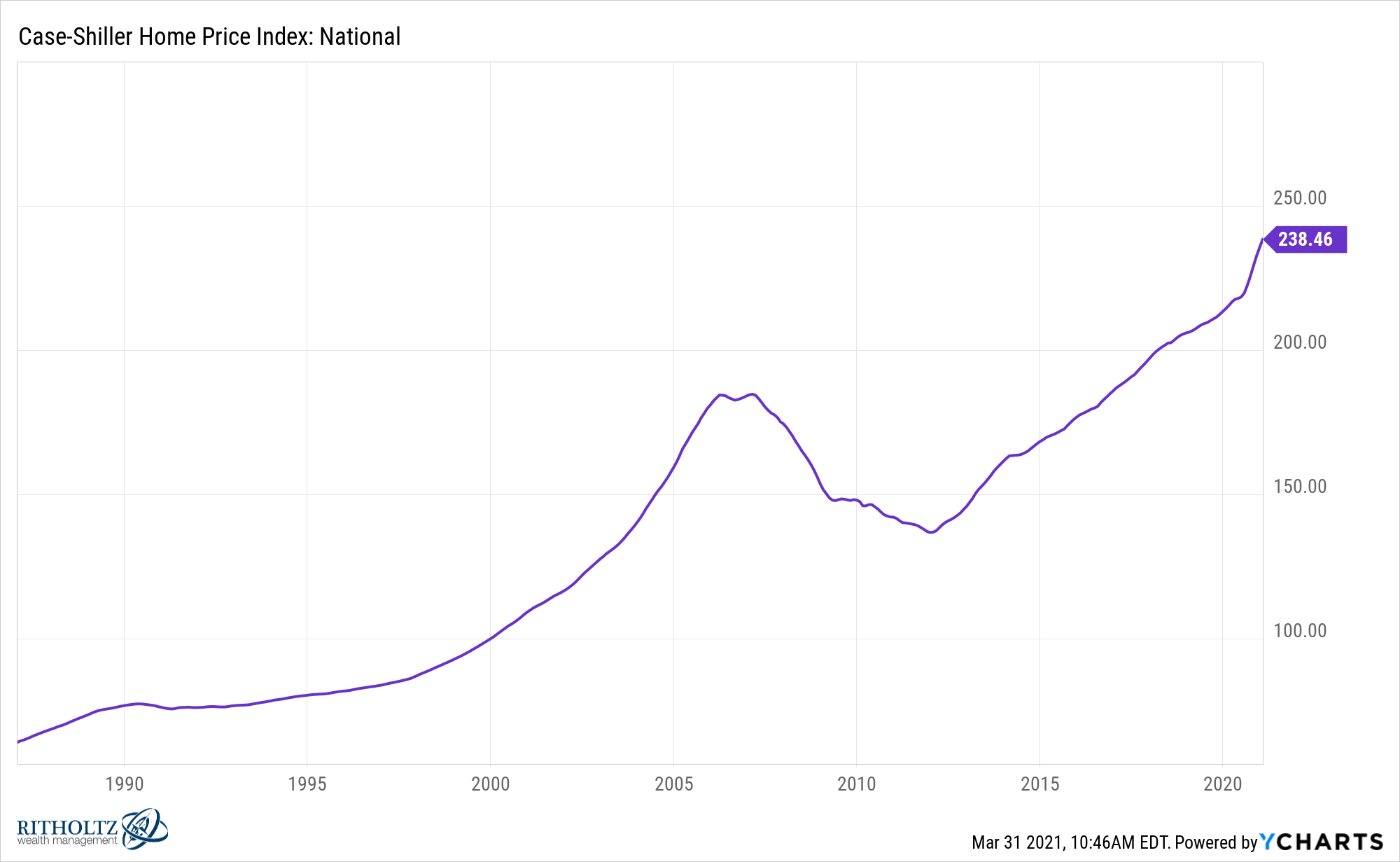

Here’s the Case-Shiller Home Price Index going back to 1987:

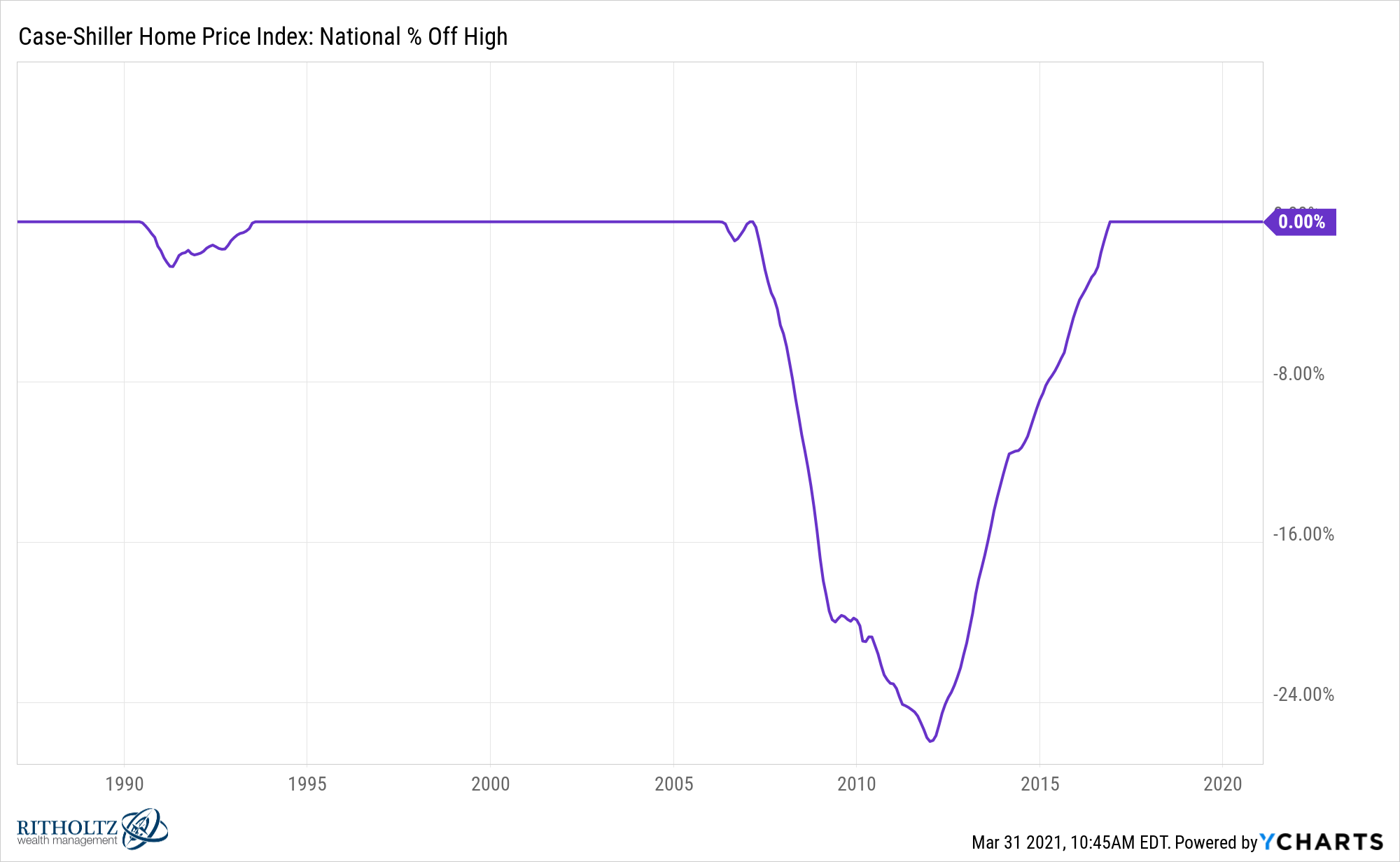

The most obvious dip came after the real estate bubble popped but there really hasn’t been many other nation-wide losses in the housing market over the past 34 years or so:

The recession in the early-1990s was nastier in some places than most people remember and it did touch off some carnage in certain real estate markets. But nationally, housing prices fell just over 2%. Other than that, the housing bust was really your only chance to buy a home at a significant discount.

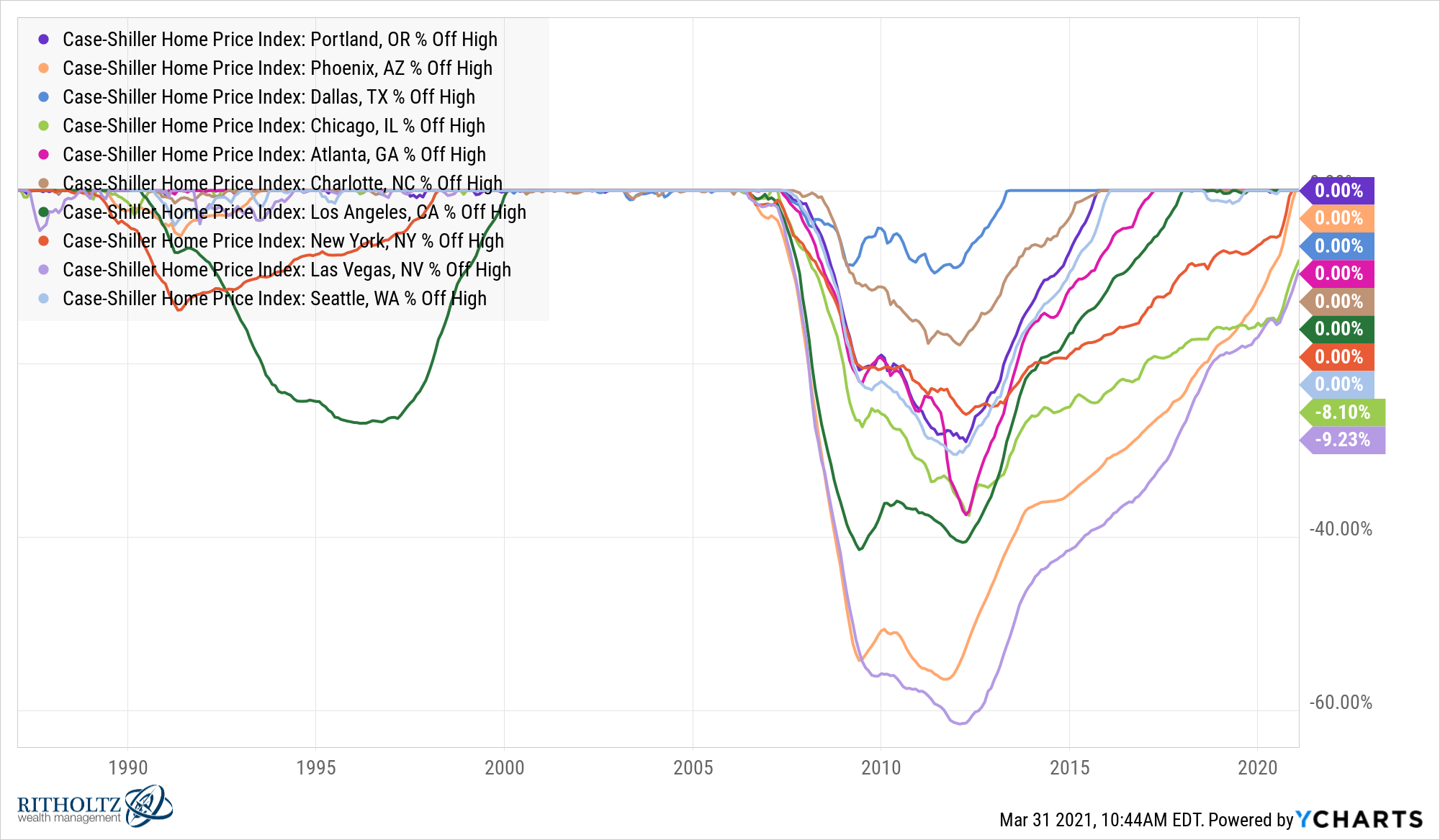

Of course, the national average masks what goes on in any individual area. You can see Los Angeles and New York City did experience a double-digit drop in prices from that 1990s pullback:

Prices in NYC fell more than 13% while housing in LA was down more than 26%. Other cities were far more resilient. And you can see the downturns were not uniform during the housing bust either.1

While rising mortgage rates could slow demand, it’s not a foregone conclusion that prices will fall. In theory, a higher discount rate would call for lower prices, all else equal. But all else is not always equal when it comes to demand for housing.

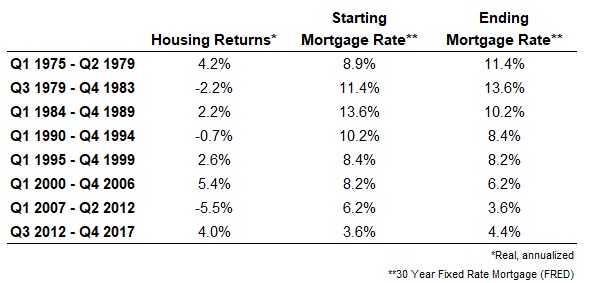

A few years ago I looked at the relationship between big moves up or down in the 30 year fixed rate mortgage to see what impact it had on real housing prices:

Sometimes rising rates have hurt prices but other times prices just kept going up. Sometimes falling rates helped prices but other times prices just kept going down. Sometimes these things operate on a lag and sometimes prices are updated in real-time.

And these are just the averages. A home has the most idiosyncratic risk of any asset. It’s not just the health of the overall housing market that helps determine a home’s value but the city, community, neighborhood, school system, location, age of the home, amenities, design and more.

Housing is an asset class where your macroeconomic forecast could be spot on for the market at large but completely off-base on the particular house you would like to buy.

You could be right about rates but wrong about demand. You could be right about nationwide housing but wrong about your particular area (or vice versa). Or you could be waiting a very long time for housing prices to fall since it’s not as common as you might think.

Owning a home is certainly not for everyone. There are reasons to hold off on this purchase. Renting is a better option for some people.

But if you know you want to buy a house I wouldn’t get too cute with the timing of that decision.

What would you regret more — missing out on the home of your dreams or missing out on a more favorable buying opportunity?

And I’m not saying there is a right answer here for everyone. There are certain people who look at this decision firmly from a spreadsheet perspective. Others are far more emotional about their home purchase.

But if you think timing the stock market is hard, timing the housing market might be even harder. Each home comes with its own landmines that could blow up your thesis on the housing market overall.

And much like the stock market, going into real estate with a long time horizon can help smooth out a poor entry point.

My rule of thumb is this — don’t buy a home you wouldn’t be comfortable living in for a minimum of 5-7 years.

Michael and I discuss the housing market and more on this week’s Animal Spirits video:

Subscribe to The Compound for these videos each week.

Further Reading:

Owning a Home is Not For Everyone

1Mainly because the gains during the housing bubble were not uniform either. The cities that saw the biggest losses tended to be those place that experienced the biggest gains in the run-up.