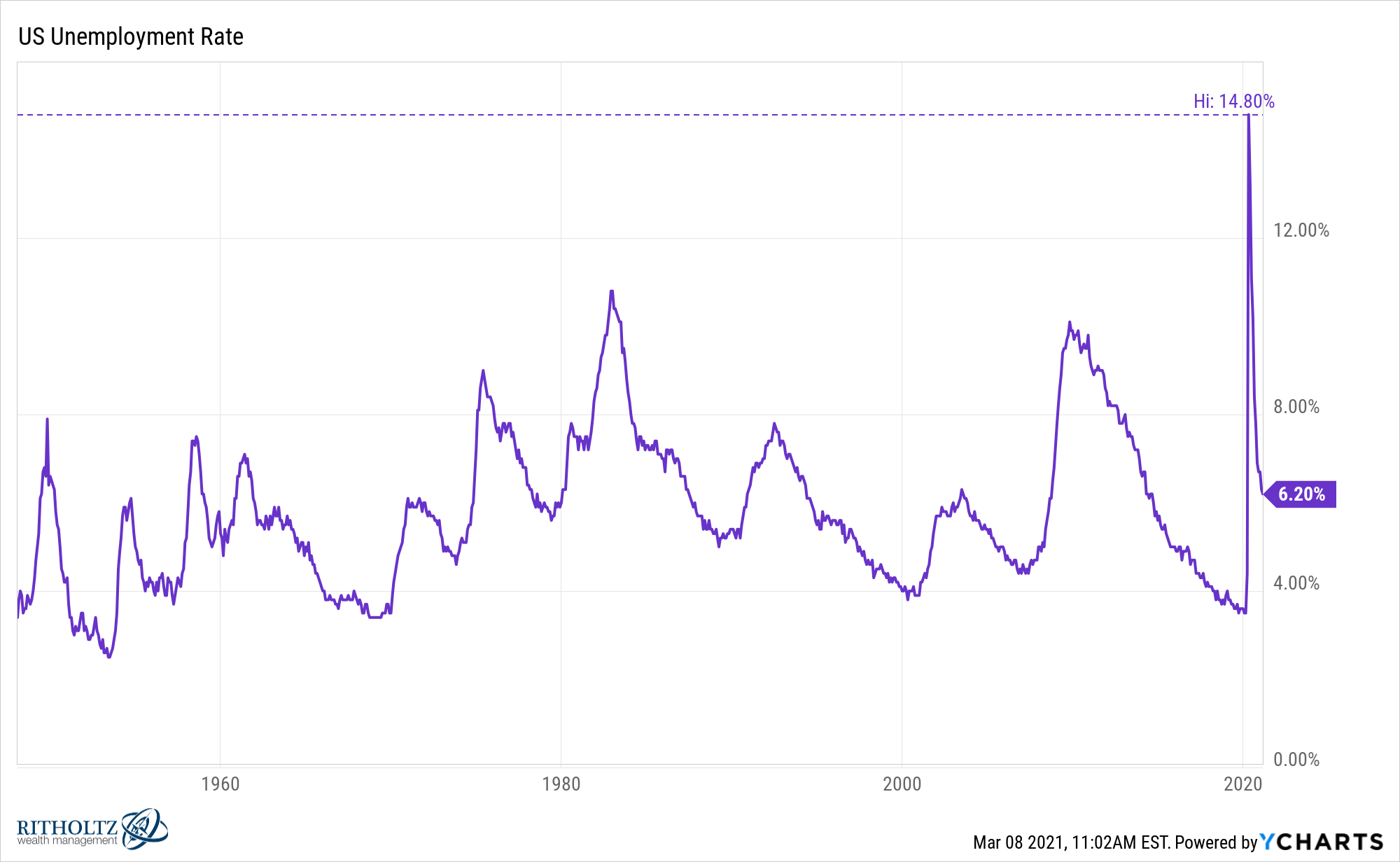

The unemployment rate is now down 60% from the pandemic high:

It’s nice to see some progress but there’s still plenty of work to do in getting more people back to work.

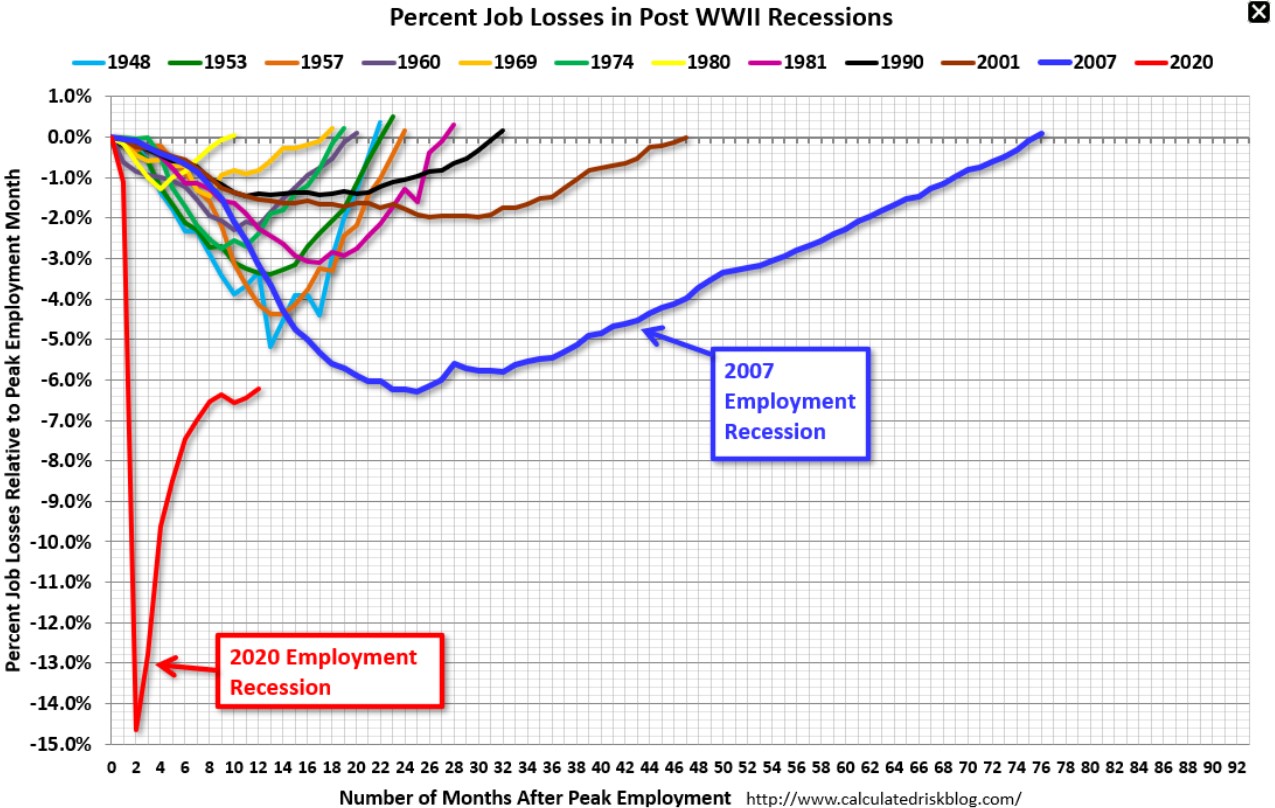

Bill McBride wrote a piece over the weekend showing the employment situation is still not in a good place despite the drop in the unemployment rate. This was by far the worst post-WWII job losses and we’re still barely back to the nadir of the Great Financial Crisis:

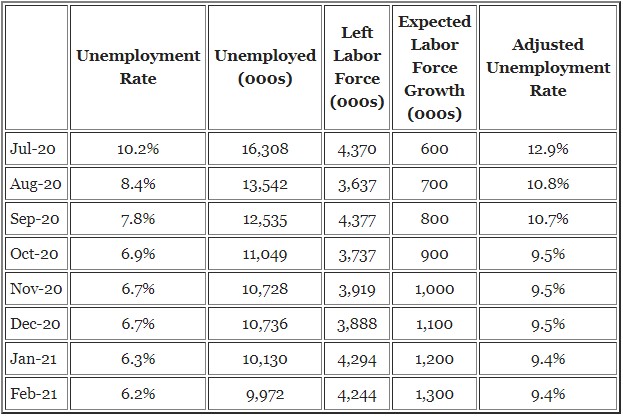

McBride also looks at an adjusted unemployment rate that takes into account the number of people who lave left the labor force:

We still have a long ways to go.

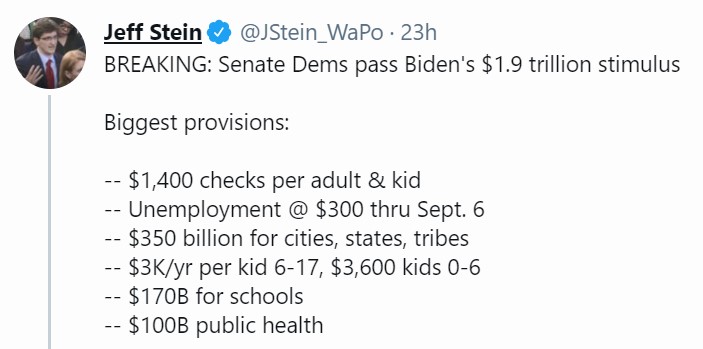

This is one of the reasons the government just passed another $1.9 trillion spending bill. There are still households and individuals who are suffering financially, through no fault of their own, because of the pandemic.

Here’s the high-level breakdown of the most recent bill from Jeff Stein:

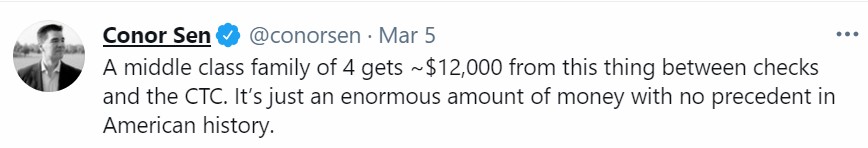

The numbers for certain households are way higher than anything that’s ever been tried before:

The Great Depression left an indelible mark on household finances because there was no government backstop. No unemployment insurance. No Social Security. No checks in the mail.

So a generation of frugal misers was born.

I don’t think we have to worry about that happening this time around. If anything, people are worried about the opposite — a nation of risk-takers and speculators.

It’s way too early to draw any concrete conclusions just yet but the total amount of money that’s helped get people through the pandemic is staggering.

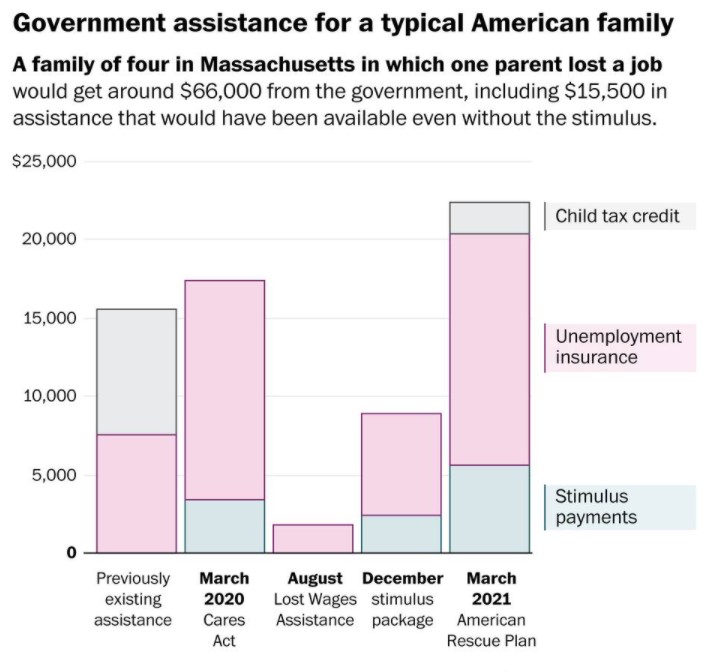

The Washington Post put together an example of a family of four where one parent lost their job:

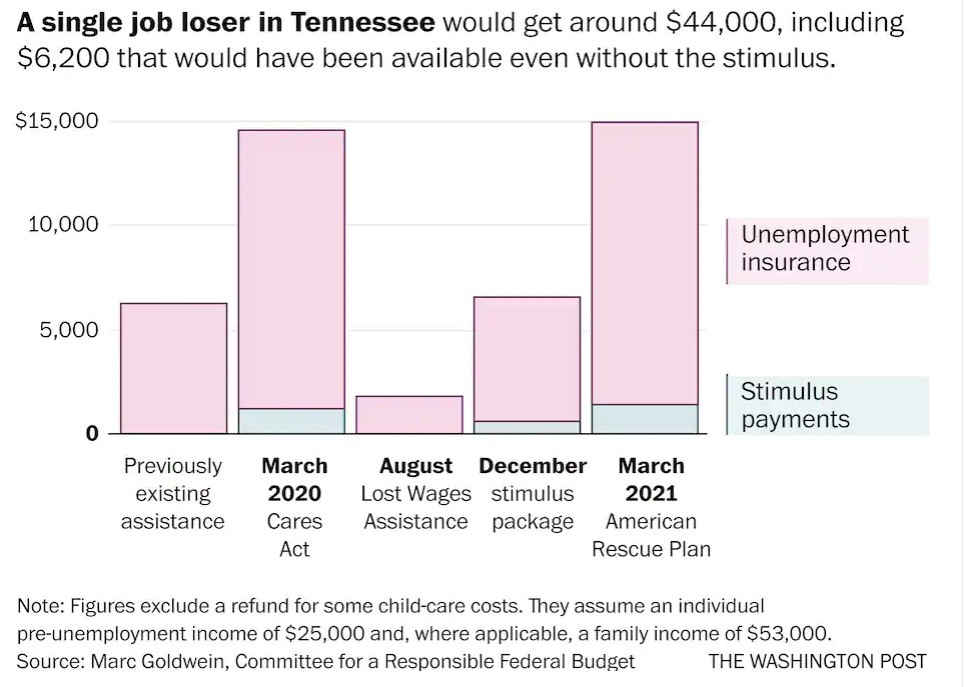

Now here’s a single person who lost their job:

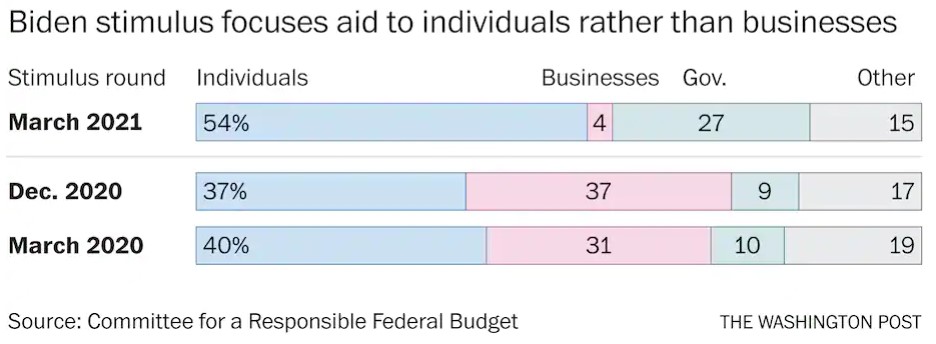

I know people are still angry about the 2008 bailouts going to Wall Street instead of Main Street but it’s different this time around:

These bills aren’t perfect. There are likely a number of households that are receiving aid who don’t need it. There are certainly businesses and households who didn’t get as much help as they need, as well.

But the Post notes the total tab is $2.2 trillion to workers and families in total from each of these bills. That’s more than the government spends on Social Security, Medicare and Medicaid combined in a given year.

There are, of course, people who are worried about this level of spending. Who is going to pay for all of this government debt? What happens if this overheats the economy and we get inflation?

These concerns are valid. There are risks here.

It should be noted that government debt doesn’t ever truly get paid back. It’s not a mortgage. One of the ways you “pay” it back is through higher economic growth and inflation.

It’s understandable why people are nervous about the prospect of inflation from all this spending. The first thing people think about when they hear the word ‘inflation’ is higher prices. Why would anyone want to pay higher prices for goods and services?

But inflation does not exist in a vacuum and it’s not all bad.

The entire reason the Fed is willing to let inflation run a little hot is because they’re trying to get to full employment.1 If that happens companies will either have to become more productive and efficient or pay more to attract talent.

This is one of the things most people miss when thinking about the ramifications of inflation. Yes, prices rise and your standard of living becomes more expensive but the only way we get sustained inflation is through wage increases. And that higher inflation could come with higher economic growth as well. The whole pie could get bigger.

You can have both at the same time.

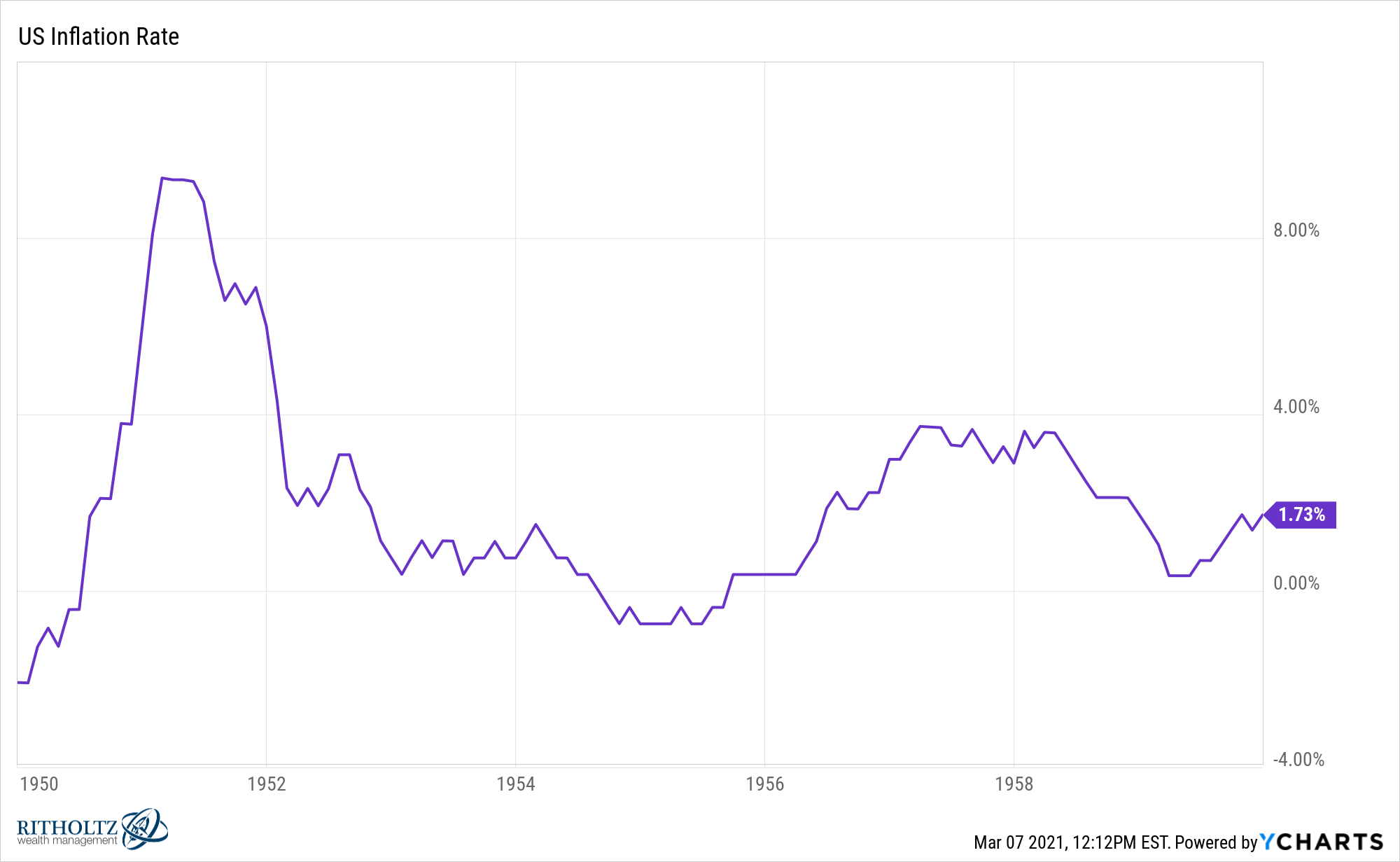

Take the 1950s, for instance. This was one of the biggest economic booms in our country’s history. This is what the inflation rate looked like in this period:

Inflation averaged more than 2% throughout the decade and spent more than one-quarter of the time above 3%, including that burst to more than 9%.

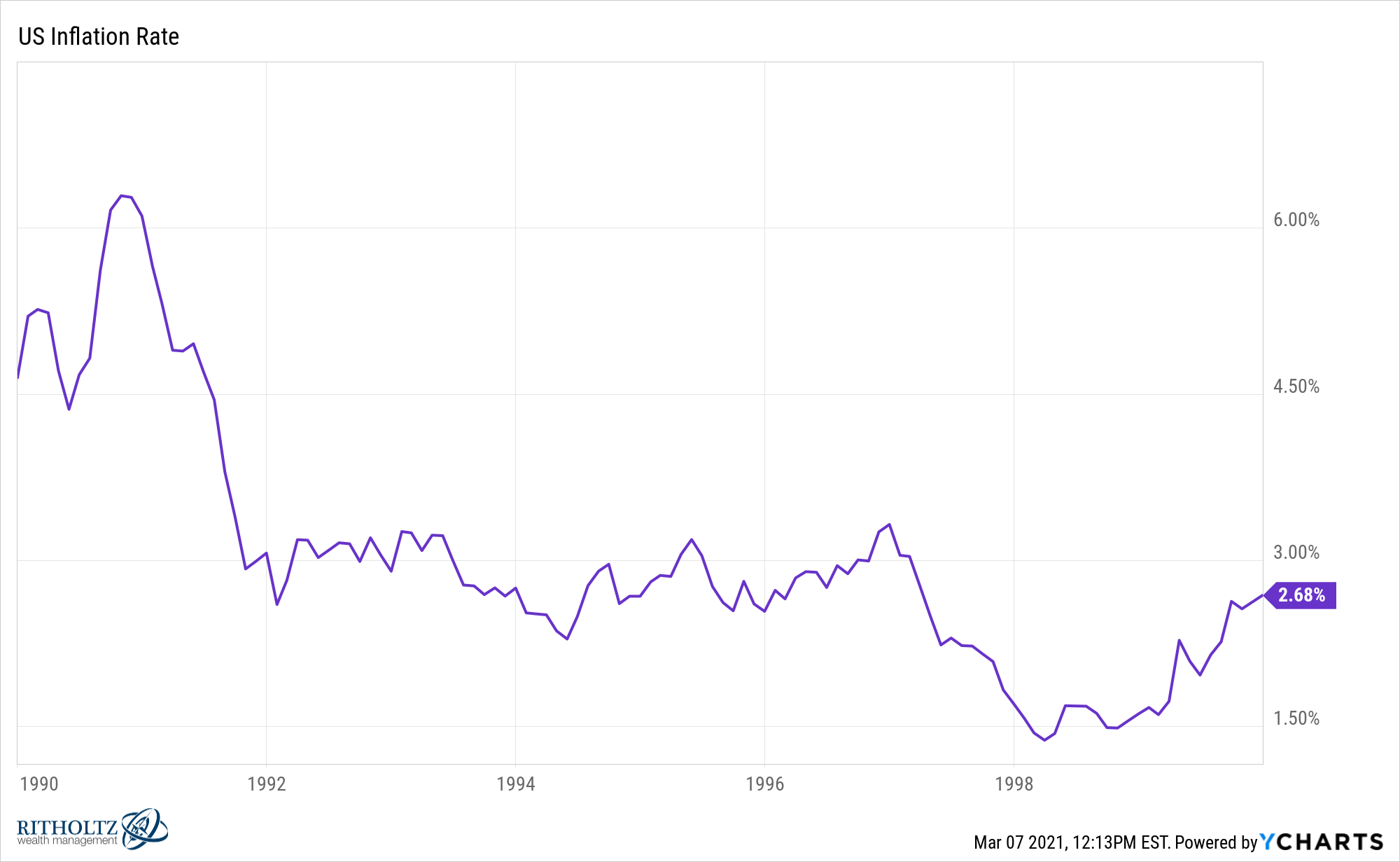

Or how about the 1990s, arguably the greatest economy ever:

Inflation averaged over 3% for the 1990s. Nearly one-fifth of the decade saw inflation above 4%.

And although it would seem like lower and middle-class households would get hit hardest from rising prices, they would also benefit the most in one other area from inflation — debt. There is massive wealth inequality in this country but also in debt.

There is roughly $14 trillion in household debt in the United States. The bottom 50% of households by wealth hold nearly $6 trillion of that debt. And the bottom 50% also has no direct ownership in the stock market. This means the bottom 50% holds no stocks and almost half the debt.

If (and it’s still an if) we were to see some inflation that would be a good thing for these borrowers and a bad thing for lenders. Inflation is your friend if you are in debt. Everyone that refinanced or took out a 3% fixed-rate mortgage in the past year should hope for a little inflation in the coming years.

It means the money you’re paying back in the future isn’t worth as much. Inflation is a good thing for fixed debt repayments from the perspective of the borrower.

Listen, I have no idea what’s going to come from all of this spending. No one does. This is unprecedented. I’m trying to see both sides of the potential outcomes.

We could see the roaring 20s. GDP growth of 4-5% over the next 3-4 years is on the table.

We could see inflation get out of control, which causes the Fed to raise rates or the government to raise taxes or both, leading to a recession.

Financial assets could take off from a booming economy or struggle because of inflation.

All I know is this is an economic experiment on a massive scale the likes of which this country has never seen before.

And for once, the lower and middle class appear to be the main beneficiaries.

Further Reading:

Could Inflation Give Us a Wonderful Buying Opportunity?

1Something they are now predicting could come as early as next year.